Sustaining Strong Communities on Maryland’s Eastern Shore – Sustaining a Healthy Shore

A good quality of life and a strong economy both require a healthy population. Healthy residents have lower medical costs and lose fewer workdays to illness. In addition, research shows that children who face health problems early on in life have a harder time succeeding in school and the workforce.[i] That’s why our investments in healthy communities are so important for a strong Eastern Shore.

Residents of the Eastern Shore face significant barriers to accessing health care, which can make it harder to prevent and treat chronic illnesses or get care quickly during an emergency. These barriers fall into three categories: insurance coverage, access to primary and specialist care, and access to emergency care.

Health coverage is a basic precondition for maintaining physical and financial health. Without insurance or coverage through programs like Medicaid and Medicare, people may avoid getting regular preventive care or seeing a doctor when they are sick due to fear of medical bills they can’t afford. This can allow chronic conditions to worsen, which puts people without insurance at a greater risk of developing serious health problems and ultimately means higher health care costs for everyone.

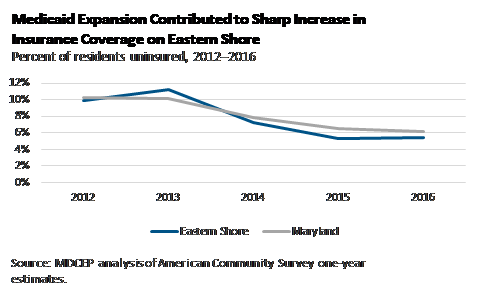

The share of Eastern Shore residents without insurance coverage has declined considerably since 2013, thanks in large part to Maryland’s decision to expand access to Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. At the same time, about 24,000 Eastern Shore residents still did not have health insurance as of 2016. Residents who were born outside the United States were especially likely to be uninsured, with 33 percent lacking health insurance between 2012 and 2016.[ii]

Health insurance on its own does not guarantee meaningful access to care. An adequate supply of health care professionals is necessary to ensure that people can get the care they need, when they need it. Several communities on the Eastern Shore have among the lowest shares of health practitioners per capita in the state, which can make it hard to get an appointment or require traveling a long distance to get to a doctor’s office.[iii]

- All five of Maryland’s counties with the fewest primary care physicians per capita are on the Eastern Shore. Somerset County has the greatest need, with only one primary care physician per 3,200 residents (just over one-third of the state average).

- Three out of five of the state’s counties with the fewest dentists per capita are on the Eastern Shore. Queen Anne’s County has the greatest need, with only one dentist per 2,700 residents (less than half of the state average).

- Two of the five Maryland counties with the fewest mental health providers are on the Eastern Shore. Caroline County has the greatest need, with only one provider per 2,500 residents (less than one-fifth of the state average).

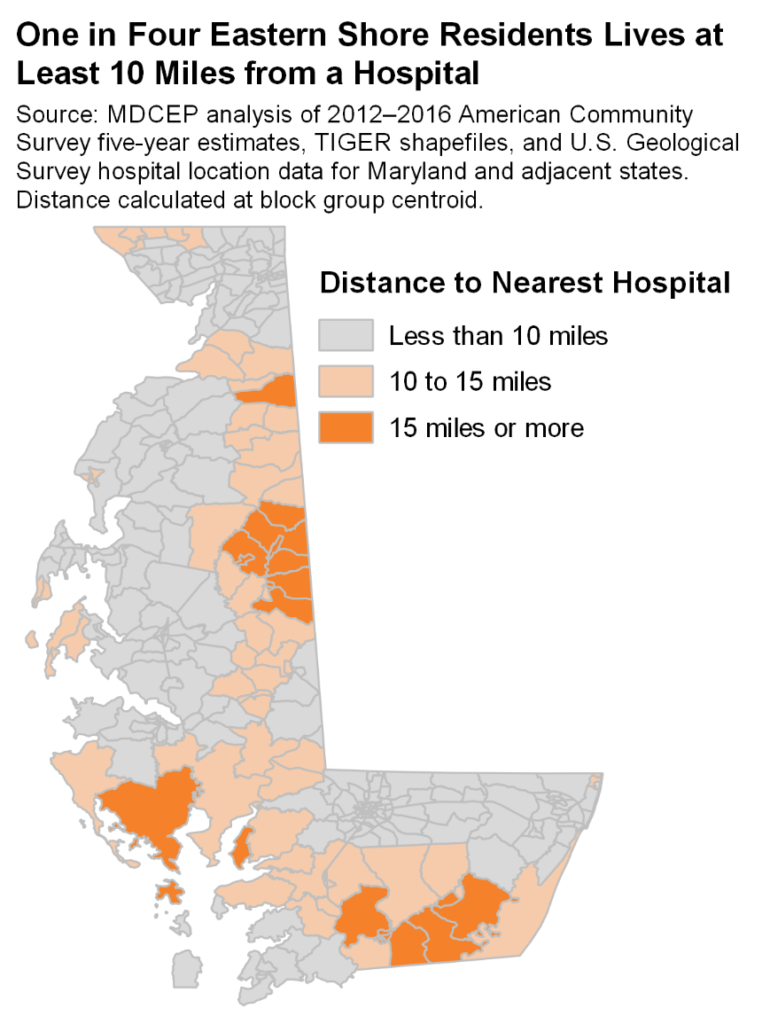

Distance can create another barrier to care in rural communities, especially in a medical emergency. Researchers have found that each additional 10 kilometers from a hospital (about 6 miles) is associated with up to a 3 percent drop in the likelihood of surviving a heart attack. One study found that patients who traveled more than 20 kilometers in straight-line distance to a hospital (about 12 miles) faced an especially high risk of death.[iv] One in four Eastern Shore residents lives at least 10 miles from a hospital, including more than half of Caroline County and Somerset County residents.[v] More than half of all Marylanders who live at least 15 miles from a hospital live on the Eastern Shore.

to care in rural communities, especially in a medical emergency. Researchers have found that each additional 10 kilometers from a hospital (about 6 miles) is associated with up to a 3 percent drop in the likelihood of surviving a heart attack. One study found that patients who traveled more than 20 kilometers in straight-line distance to a hospital (about 12 miles) faced an especially high risk of death.[iv] One in four Eastern Shore residents lives at least 10 miles from a hospital, including more than half of Caroline County and Somerset County residents.[v] More than half of all Marylanders who live at least 15 miles from a hospital live on the Eastern Shore.

Residents of the region are more likely than other Marylanders to experience a range of health problems, partly as a result of population age, higher poverty rates, and less access to health care.[vi]

- Somerset County has both the highest infant mortality rate (11.4 deaths per 1,000 live births between 2010 and 2016) and the highest child mortality rate (148.4 deaths per 100,000 children between 2013 and 2016) in the state. Four Eastern Shore counties are among the top five in Maryland for infant mortality and for child mortality, with Somerset and Caroline counties among the top five in both age groups.

- As of 2014, residents of Dorchester County were the most likely in Maryland to have diabetes, with Somerset and Worcester counties also among the top five in the state.

- Between 2014 and 2016, Caroline, Cecil, and Somerset counties were among the five Maryland counties in which residents were most likely to die relatively early in life.[vii]

Policy Solutions

Recruit More Eastern Shore Residents into Health Care Professions

The need for health care workers on the Eastern Shore is an opportunity to create high-quality jobs for the region’s residents. The key to meeting both needs is a long-term investment in recruitment, education, and training.

- Target diverse professions. Efforts to build the Eastern Shore’s homegrown health care workforce should include physicians, dentists, and other health care practitioners as well as high-demand health care support occupations like home health aides. The need for these workers will only increase as population aging increases demand for long-term care.

- Invest in high-quality jobs. Policymakers can simultaneously improve health care and strengthen the region’s economy by pairing training efforts with worker protections. This is especially necessary in health care support occupations where low wages currently contribute to high turnover.[viii] Ensuring that care workers earn enough to support their families is an important step to improving quality and continuity of care.

Increase Access to Care in the Near Term

While the best solution to the Eastern Shore’s needs in the long run is to build a strong homegrown health care workforce, the region would also benefit from policies to improve access to care today.

- Encourage health professionals to work on the Eastern Shore. State and local policymakers should work to make the Eastern Shore a more attractive location for health care workers. Today, typical health practitioners and technical workers in the region earn 15 percent less per year than typical workers in these occupations statewide.[ix] In health care support occupations such as home health aides, typical pay in the region is 11 percent lower than the statewide average. Worker protections like living wage requirements can make the region more attractive to workers in lower-paying occupations, while forgiving student loans of health professionals who take jobs on the Eastern Shore could help attract highly trained workers.

- Use the full menu of medical credentials. While physicians are in the best position to meet some of the region’s needs, such as access to specialist care, medical professionals with other credentials can provide primary care and certain other services. Some of these providers are already in widespread use, such as nurse practitioners. Legislation may be necessary in other cases to allow a wider range of professionals to provide care. For example, Vermont in 2016 passed legislation to join other states in allowing dental therapists to perform certain procedures that had previously been the sole preserve of dentists.[x] Similar legislation passed the Maryland House of Delegates in 2018, but stalled in the Senate.[xi]

- Invest in school-based health centers. School-based health centers allow students to access primary care and other health services beyond those available from a school nurse, typically provided by a physician’s assistant. Nineteen schools in Caroline, Dorchester, Talbot, and Wicomico counties currently have school-based health centers.[xii] The state should include more widespread school-based health centers in its school finance reform package.

Expand Emergency Care Capacity in Underserved Areas

Policymakers should explore ways to improve access to emergency care in areas that do not have a hospital nearby. Reducing the distance patients must travel in the event of a heart attack or other medical crisis has the potential to save lives. While building full-service hospitals would likely generate significant costs while duplicating non-emergency medical services already available at existing facilities, there are other options, such as free-standing medical facilities with emergent and urgent care capabilities and mobile intensive care ambulances.[xiii]

Target Resources to the Highest-Need Communities

While health care needs exist across the Eastern Shore, policymakers should act most quickly to improve access to care in communities where the needs are most urgent.

- Somerset County: Somerset County has the greatest need among all Maryland counties for primary care providers and interventions to reduce infant and child mortality. Residents of Somerset County are also more likely than many Marylanders to live relatively far from emergency care, to have diabetes, and to die at a relatively young age.

- Caroline County: Residents of Caroline County are more like than those in any other part of Maryland to live a significant distance from emergency care. They also have the least access to mental health care providers. The county would also benefit from additional primary care providers and interventions to improve infant mortality, child mortality, and overall life expectancy.

- Dorchester County: Residents of Dorchester County are more likely than those in any other part of Maryland to be diagnosed with diabetes and babies in Dorchester are among the most likely to be born underweight. The county also has limited access to primary care providers.

< Supporting Broad Prosperity | Facing the Climate Change Present >

[i] See for example John Fantuzzo, Whitney LeBoeuf, and Heather Rouse, “An Investigation of the Relations between School Concentrations of Student Risk Factors and Student Educational Well-Being,” Educational Researcher 43 no. 1, 2014, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.3102/0013189X13512673. This study found that Philadelphia students who were born prematurely or with low birth weight scored 2.9 points lower on reading assessments and 3.8 points lower on math assessments than otherwise-similar students at the same school.

[ii] MDCEP analysis of American Community Survey five-year estimates. A five-year period is used to obtain a reasonably precise estimate for a small population.

[iii] All data in this paragraph from County Health Rankings, http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/

[iv] Daniel Avdic, “A Matter of Life and Death? Hospital Distance and Quality of Care,” CINCH Health Economics Research Center Working Paper Series, 2015, https://cinch.uni-due.de/fileadmin/content/research/workingpaper/1501_CINCH-Series_avdic.pdf

Jon Nicholl, James West, Steve Goodacre, and Janette Turner, “The Relationship between Distance to Hospital and Patient Mortality in Emergencies: An Observational Study, Emergency Medicine Journal 24(9), 2007, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2464671/

[v] MDCEP analysis of 2012–2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates, TIGER shapefiles, and U.S. Geological Survey data on hospital locations for Maryland and neighboring states. This analysis is based on straight-line (geodesic) distance from a hospital to the geographic center (centroid) of a census block group. This analysis has two major limitations. First, using block group centroids introduces error because in reality residents live throughout a block group, not at its geographic center. For some residents this will lead to underestimating the distance to a hospital, while for others it will lead to overestimating this distance. Second, straight-line distance is an imperfect proxy measure for driving time, the relevant consideration in an emergency. Driving distance is always greater than or equal to straight-line distance, but the relationship between the two depends on the directness of the route. Furthermore, the same distance will likely be more survivable if local roads allow faster speeds.

[vi] All data in this paragraph from County Health Rankings.

[vii] Specifically, these counties lost more years of life per capita due to residents dying under the age of 75 than most other counties in Maryland.

[viii] See Christopher Meyer, “Expanding Home Care Options in Maryland: Paying Independent Home Care Aides Appropriately Would Bring Real Benefits at an Affordable Price,” Maryland Center on Economic Policy, 2017, http://www.mdeconomy.org/homecare/

[ix] See Table 2. Note that while housing and other necessities are generally less expensive on the Eastern Shore than elsewhere in Maryland, many health care practitioners who choose to work in the region would still face high student debt costs.

[x] John Grant and Andrew Peters, “Vermont Passes Legislation Authorizing Dental Therapists,” Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2016/06/20/vermont-passes-legislation-authorizing-dental-therapists

[xi] House Bill 879 of 2018, http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/webmga/frmMain.aspx?pid=billpage&stab=01&id=hb0879&tab=subject3&ys=2018RS

[xii] Maryland Assembly on School-Based Health Care, http://masbhc.org/what-is-school-based-health/maryland-sbhcs/

[xiii] See for example Nir Harish, Jennifer Wiler, and Richard Zane, “How the Freestanding Emergency Department Boom Can Help Patients,” NEJM Catalyst, 2016, https://catalyst.nejm.org/how-the-freestanding-emergency-department-boom-can-help-patients/