Sustaining Strong Communities on Maryland’s Eastern Shore – Overview and Profile

Maryland’s Eastern Shore is a place with significant assets including natural beauty, productive farmland, and an iconic seafood industry. The region also faces significant challenges—some that would be familiar to residents of any other part of Maryland, and some that stem from the region’s distinctive geography and development patterns. The Eastern Shore’s labor market is characterized by higher unemployment and lower wages than other parts of the state. Partly as a result, families in the region are more likely to struggle to afford the basics. Parts of the Shore lack adequate numbers of health care providers and require residents to travel long distances for care, even in the event of a medical emergency. Finally, while the threat of climate change looms over our entire state, it is already a dangerous reality for many of the Eastern Shore’s coastal communities. Actions – or in some cases inaction – by the federal government could exacerbate each one of these challenges.

State policymakers as well as local governments on the Eastern Shore must make important choices in responding to these challenges. Ineffective strategies, such as an emphasis on tax breaks and low labor costs, will only undermine the foundations of prosperity in the region. Worse yet, the state could embrace “bus ticket economics,” encouraging residents to leave their communities and seek work elsewhere. There is a better path, starting by recognizing that Maryland’s regions depend on one another and our state can only thrive if all residents have the support they need to succeed. The state and local governments should invest in proven strategies to sustain strong communities on the Eastern Shore.

- Invest in education and training. A well-educated workforce is one of the strongest determinants of economic growth. Investing in education and training from early childhood through adulthood will strengthen the Eastern Shore’s economy in both the short and long term. The state should enact a robust education reform package based on the Kirwan Commission’s forthcoming recommendations, including both increased state investments and a requirement that counties fully fund their share of school system costs. Policymakers should expand meaningful access to community college by ensuring that students are able to afford necessities. Finally, the state and local workforce development boards should continue and strengthen successful approaches to workforce development.

- Protect and strengthen investments in economic security. Federal and state investments in economic security bring enormous benefits to the Eastern Shore, but unreliable federal support threatens families who depend on these investments, as well as the communities whose economies those families support. The state should continue to develop plans for protecting families in the case of damaging federal cuts. The state should also ensure all families can keep a roof over their head and see a doctor without going into debt.

- Pair evidence-based support for businesses with protections for workers. Too often, Maryland’s economic development policies rely on costly and ineffective approaches like corporate tax breaks. The state should move away from this strategy and instead invest in customized business services like training, credit assistance, and technical assistance. Whenever the state directly supports businesses, it should maximize the benefit to communities through strong worker protections. Promising approaches include living wage protections, sanctions for companies with labor standard violations, and well-designed incentives for employers to go beyond minimum legal standards.

- Create good jobs meeting the region’s health and climate needs. There is plenty of work to be done on the Eastern Shore—and there are many workers willing to do it. Increasing health care access, caring for aging residents, and adapting to climate change will all take work. In some cases, workers would benefit from greater investments in education and training so they can build the skills this work requires. In other cases, the skills are there but capital is lacking. The state should build the required skills base through education and training and create high-quality jobs to address pressing needs. It can do so either through direct public employment or by partnering with community organizations. Either case requires strong worker protections to ensure our investment creates family-sustaining jobs.

- Improve state and local tax policies. Maryland’s state and local budgets reflect where our priorities lie. Effective responses to the challenges facing Eastern Shore communities will require increased state and local investments, which is possible only with a well-functioning revenue system. The state should clean up and rebalance its tax code to close corporate loopholes, ensure wealthy individuals are contributing to the services we all rely on, and stretch low-wage workers’ earnings. These reforms will have the added benefit of making Maryland’s tax code more equitable for the Eastern Shore. Finally, counties that have rigid tax limitations on the books should repeal those limitations, enhancing their capacity to invest in the pillars of the modern economy and respond to emergencies.

Profile of the Eastern Shore

Maryland’s Eastern Shore consists of the state’s nine counties on the Delmarva Peninsula:[i] Caroline, Cecil, Dorchester, Kent, Queen Anne’s, Talbot, Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester. The region was home to 455,000 people as of July 2017, an increase of 6,000 or 1.3 percent from its 2010 population.[ii] While Eastern Shore communities share several unifying characteristics, there is also considerable variation. The region includes both rural and urban communities; predominantly white and racially diverse communities; affluent communities and economically struggling ones.

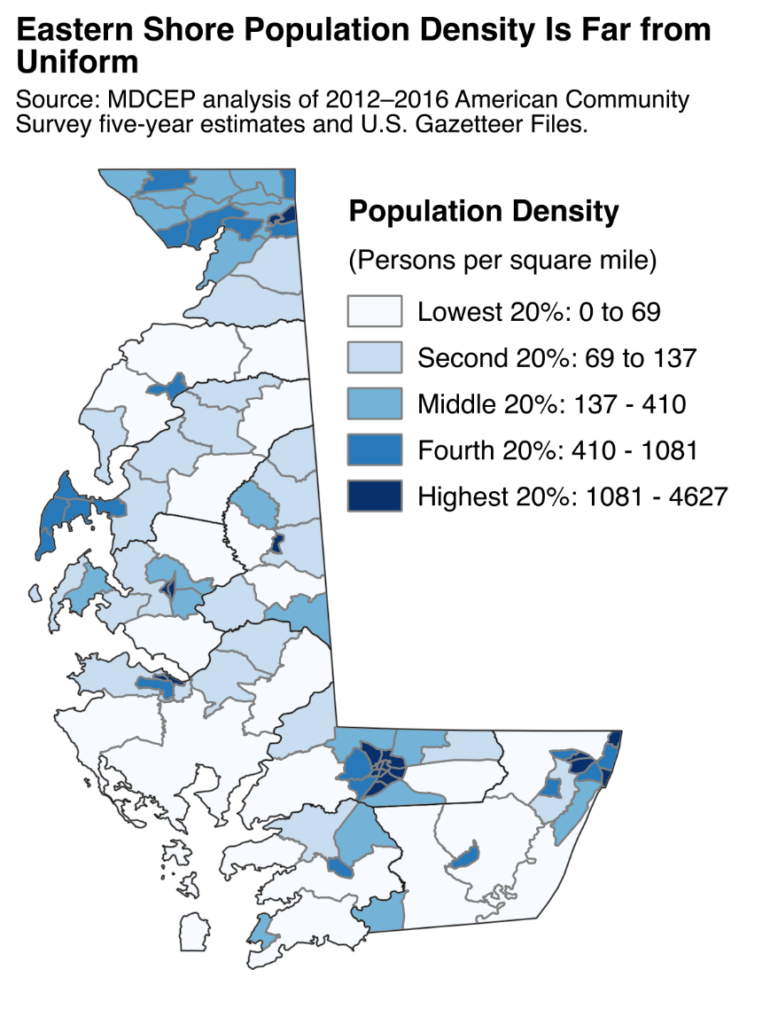

The Shore is more rural than the state as a whole, with an average population density of 138 residents per square mile. That is just over one-fifth of the state average of 623 residents per square mile.[iii] However, these averages conceal considerable variation within the region. For example, 15 percent of Eastern Shore residents live in communities with less than half the region’s average density, while 10 percent live in neighborhoods with more than 2,000 residents per square mile (between Prince George’s County and Montgomery County in density).[iv] Half of residents live in a community with less than 278 residents per square mile, close to the average density of Wicomico County.

The Eastern Shore has an older population than the state overall, with 19 percent of its residents being ages 65 or older (compared to 15 percent for the state overall).[v] Both the Eastern Shore and the state overall have experienced population aging in recent years, with the share ages 65 or older increasing by 3.2 and 2.6 percentage points, respectively. Children under 18 years old account for similar shares of the under-65 population on the Eastern Shore and elsewhere in Maryland.

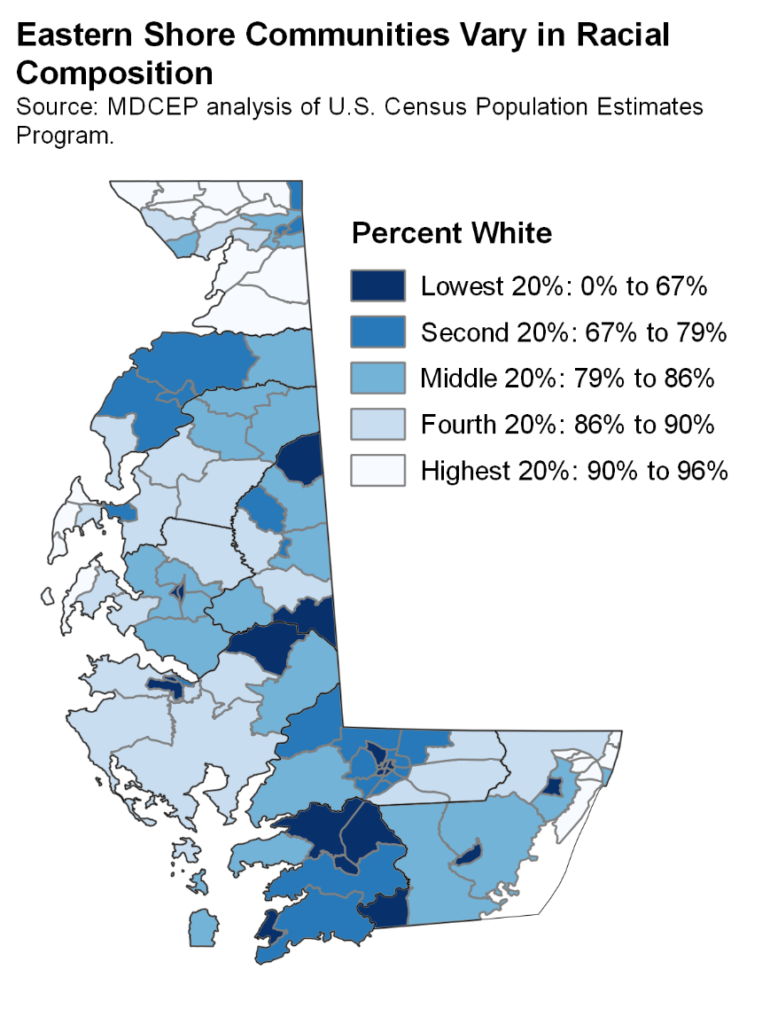

Nearly three-quarters of Eastern Shore residents are white, compared to just over half of Maryland residents overall.[vi] Black residents constitute 17 percent of the Eastern Shore population, while 5 percent of residents are Latinx.[vii] Although the region’s racial composition is significantly different from other parts of Maryland, it has experienced similar trends in recent years. The white population has declined by 2 percent since 2010 while the Latinx population has increased by 26 percent. There has been modest population growth in the number of Black residents of the Eastern Shore and other people of color. Like population density, racial composition differs significantly across the region. Queen Anne’s and Cecil counties are both over 85 percent white, while 42 percent of Somerset County residents are Black.

Eastern Shore residents have completed fewer years of education compared to statewide averages. While adults in the region are nearly as likely as those elsewhere in Maryland to have completed high school (88 percent of Eastern Shore residents 25 or older, compared to 90 percent statewide), they are less likely to have attended college.[viii] On the Eastern Shore, 26 percent of adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher and 33 percent have an associate’s degree or higher. Statewide, 38 percent of adults have at least a bachelor’s degree and 45 percent have at least an associate’s.

| Next section: Supporting Broad Prosperity >

[ix] Region-wide averages also mask variation in educational levels. For example, 21 percent of Somerset County residents who are at least 25 years old did not complete high school, compared to 8 percent in Queen Anne’s County.

[i] Cecil County, located at the northern tip of the Chesapeake Bay, is included in some definitions of the Eastern Shore and excluded from others. For the purposes of this report, the Eastern Shore is defined to include Cecil County.

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates Program and 2010 decennial census.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] MDCEP analysis of 2012-2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates and U.S. Gazetteer Files. Census tracts are the geographic unit of analysis.

[v] MDCEP analysis of U.S. Census Population Estimates Program.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] “Latinx” refers to persons of any gender who identify themselves as having Hispanic or Latino origin on publicly administered surveys.

[viii] MDCEP analysis of 2012–2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

[ix] This difference is not primarily due to the region’s age composition. For example, 28 percent of 35–44-year-olds on the Eastern Shore and 43 percent of 35–44-year-olds statewide have completed at least a bachelor’s degree.