The War on Poverty at 50

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty, a set of federal policies that President Johnson announced in his 1964 State of the Union Address. This anniversary provides us with the opportunity to consider the impact and implications of safety net and social insurance programs at a time when poverty persists and inequality is increasing. Nonetheless, anti-poverty programs have significantly improved the lives of millions of Americans and have had important long-term benefits.

Building on the Great Society’s Legacy

President Johnson’s original War on Poverty was part of his ‘Great Society’ initiative and included major programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, federal funding for public education and college loans, and expanded and permanent food stamp program, and expanded social security benefits. Today, these programs are complemented by more recent policies that share the goal of reducing poverty and providing economic opportunity for the working poor. These programs include the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, and WIC, which helps improve nutrition for young children and their mothers.

In addition, many original great society programs have been expanded. Maryland is one of 26 states to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, saving money in the process, while the original food stamp program has become the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP.

Evaluating the War on Poverty

While anti-poverty and social insurance programs do much to improve people’s lives, that 50 million Americans, including 13 million children lived in poverty in 2012 is evidence that there remains much work to do to foster broad prosperity. However, we cannot simply view the persistence of poverty as evidence that government programs to alleviate it are ineffective. Instead, we must consider how these programs not only improve people’s lives but keep more people from falling into poverty.

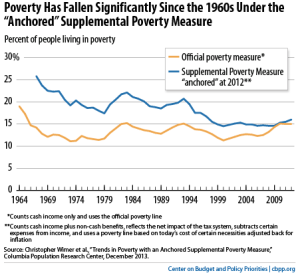

One method of doing so is the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure. In contrast with the official national measure of poverty that is used to calculate the Federal Poverty Level and is based on narrow measures of income and expenses to determine whether individuals and families make enough money to satisfy their basic needs, the Supplemental Poverty Measure seeks to account for both the full range of expenses that Americans face as well as the benefits they receive from the government. The Supplemental Poverty Measure takes into account both cash income as well as non-cash and tax-based benefits, such as SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and rental assistance. The Supplemental Poverty Measure also seeks to more fully account for the range of expenses that individuals and families face such as income and payroll taxes, out-of-pocket medical expenses, and child care, as well as geographic differences in living costs.

(click to enlarge)

When measuring poverty using the Federal Poverty Level, poverty has increased slightly from 14 percent in 1967 to 15 percent in 2012. But a new study by researchers at Columbia University applies the Supplemental Poverty Measure to this time period, and finds that safety net and social insurance programs have contributed to reducing the percentage of Americans in poverty from 26 to 16 percent between 1967 and 2012. Further, the authors argue that the safe

ty net has been particularly important in keeping children and senior citizens out of poverty, as the Supplemental Poverty Rate fell from 29 percent to 19 percent among children, and it fell among the elderly from 47 percent to 15 percent.

ty net has been particularly important in keeping children and senior citizens out of poverty, as the Supplemental Poverty Rate fell from 29 percent to 19 percent among children, and it fell among the elderly from 47 percent to 15 percent.

(click to enlarge)

But more than keeping individuals and families out of poverty, these programs have important long-term effects as well. For example, a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research of the nationwide expansion of nutrition assistance in the 1960s and 70s found that poor children who had access to food stamps (and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy) were less likely to have stunted growth, heart disease, or be obese later in life than those without access to nutrition assistance. Children whose families received nutritional assistance were also more likely to graduate from high school. More broadly, access to health insurance through public programs, especially Medicaid, have reduced infant mortality considerably.

The Columbia Supplemental Poverty Measure study also addresses the expansion of the safety net that occurred in the wake of the great recession, including additional tax credits, extended unemployment benefits and a more generous SNAP program, in keeping poverty stable during this time. Had the safety net not been expanded to address the recession, the study’s authors argue that poverty would have increased by 5 or 6 percentage points. This is particularly noteworthy as some policy makers at the national level are refusing to extend emergency unemployment insurance and seek to further cut SNAP assistance even after the post-recession expansions have expired.

More Work to Do

But the persistence of poverty, by any metric, is important as well, and is indicative that despite the importance of safety net and social insurance programs, economic conditions have worsened for those with low incomes. The percentage of men who are employed has decreased from 87 percent to 74 percent since President Johnson’s began the War on Poverty and long-term unemployment persists in the wake of the Great Recession. The struggling labor market plays a key role in the persistence of poverty. The poverty rate is 3 percent for those with full time jobs, and 33 percent for those that are not working, according to statistics provided by UC Davis. Thus, poverty persists because of the failure of government programs intended to end it, but jobs that might help workers escape poverty on their own are not there.

But this story is not the same for all Americans since the start of the War on Poverty. During this time, the share of income gained by the top 1 percent of households has doubled, from 11 percent to 22 percent. Meanwhile, the share of income going to the bottom 20 percent has decreased. Clearly, wealth has accumulated unevenly since President Johnson sought to end poverty, hampering these efforts.

As Maryland’s 2014 legislative session begins today, we will be keeping track of how proposed laws can reduce inequality and foster broad prosperity for all Marylanders. Check back here for more on the War on Poverty and the work that remains.