The State of Working for American Indians in Maryland

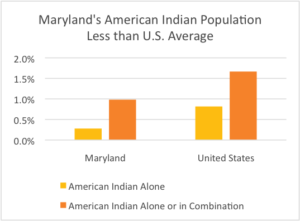

Maryland is home to about 58,000 American Indians, about 1 percent of the state’s population. Although they have the longest history in the state of any of Maryland’s residents, they often do not have the same access to prosperity as other Marylanders. Compared to the state average, American Indians in Maryland have less access to good educational opportunities, are more likely to struggle to make ends meet, and experience more health problems.

Because American Indians in Maryland are more likely to have low incomes or have difficulty finding work, policies such as expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, raising the minimum wage, and funding job training programs will have a disproportionate benefit for American Indians. Additionally, policymakers should consider key proposals that help meet the particular needs of that segment of our community. For example, Maryland should fund culturally specific addiction treatment programs and apply for available federal education funds that would allow schools to better support American Indian students.

Basic Facts

- Of the 58,000 American Indian people who are residents of Maryland, about 41,000 also consider themselves part of another racial group.

- Maryland’s population is 0.3 percent people who are American Indian alone is 0.3 percent .[i]

- With 3,000 American Indian residents, Montgomery County is home to the largest number of American Indians in the state.

- Charles County is home to the largest share of American Indian Marylanders, with 0.7 percent of this county’s residents reporting American Indian as their only racial identity.

Education

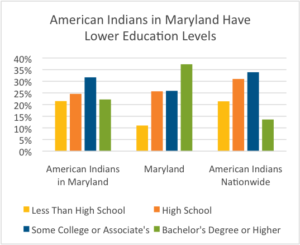

American Indians in Maryland do not have the same access to good educational opportunities as other residents of the state. They live in less adequately funded school districts and attend college at lower rates. Improving educational opportunities for American Indian Marylanders would mean better job prospects later in life.

- One in five adult American Indians in Maryland does not have a high school diploma, compared to about one in 10 Marylanders overall.

- A similar share of American Indian Marylanders has a four-year college degree—22 percent—to those who lack a high school diploma, well below the statewide rate.

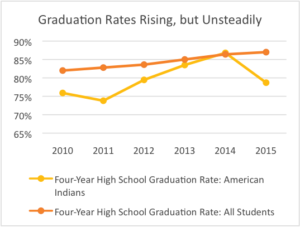

- A rising share of American Indian students in Maryland finish high school in four years, and their graduation rate is getting closer to that of other students. However, this progress is uneven, with the four-year graduation rate falling between 2014 and 2015.[ii]

- School districts with a larger share of American Indian students are less adequately funded than districts with fewer American Indian students. A 10 percent increase in the share of American Indian students is associated with a 1.4 percent decline in funding adequacy.[iii]

Employment, Income, and Poverty

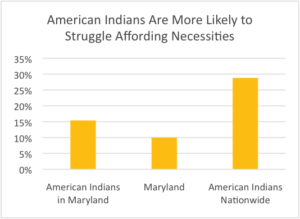

American Indians in the state face more challenges in the job market than other Marylanders, resulting in lower incomes and more difficulty affording basic necessities. Enacting policies that support workers would help more American Indian families make ends meet.

- A typical American Indian household in Maryland brings home about $54,000 per year. This is more than the typical income among American Indian families nationwide, but 27 percent less than the state’s median income.

- More than one in seven American Indian Marylanders

struggle to make ends meet, with family income below the federal poverty line—about $24,000 for a family of four.

struggle to make ends meet, with family income below the federal poverty line—about $24,000 for a family of four. - In Maryland, 14 percent of American Indian children live in families struggling to afford necessities—about the same share as in the state overall. Nationwide, more than a third of American Indian children live in poverty.

- One in four American Indian households in Maryland get help putting food on the table through the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps. SNAP is an essential tool for ensuring that American Indian Marylanders—especially children—do not go hungry.

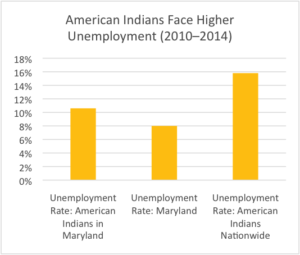

- American Indian Marylanders faced greater barriers to employment than other residents of the state between 2010 and 2014. During this period, one in ten American Indian Marylanders who wanted to work could not find jobs.

- Nationwide, unemployment among American Indians fell by about a third from 2010 to 2015, but members of this community were still twice as likely as other Americans to face difficulty finding work.[iv]

Health

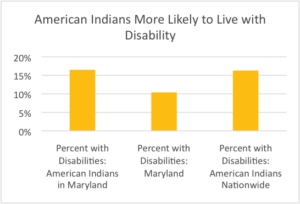

American Indian Marylanders have less access to health insurance and often worse health outcomes than others in the state. By keeping insurance affordable and funding programs to address this community’s specific health needs, we can ensure that American Indians have equal access to the care they need.

- American Indian people in Maryland are more likely to have a health condition that makes daily tasks more difficult, with 16 percent living with a disability. Overall, one in ten Marylanders has a disability.

- Twelve percent of American Indian mothers in Maryland receive no prenatal care, or only receive care late in pregnancy. By comparison, 9 percent of Maryland mothers overall receive no or late prenatal care.[v]

- American Indians born in Maryland are the least likely of all racial and ethnic groups to have a low birth weight, with this condition affecting one in 20 American Indian infants in the state. However, infant mortality is higher in this community than in the state overall. Every year, about one in 100 American Indian infants in Maryland die.[vi]

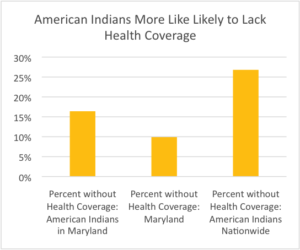

- American Indians are more likely than other Marylanders to lack access to health insurance.

From 2010 to 2014, 16 percent of American Indians in the state were uninsured, compared to 10 percent of all Marylanders.

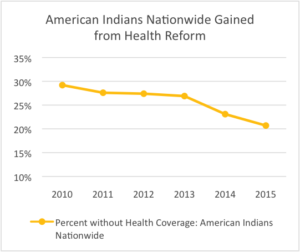

From 2010 to 2014, 16 percent of American Indians in the state were uninsured, compared to 10 percent of all Marylanders. - Nationwide, the share of American Indians without health insurance fell by more than 8 percentage points between 2010 and 2015,[vii] thanks to coverage expansions under the Affordable Care Act. However, American Indians were still more than twice as likely as other Americans to lack access to health insurance last year.

Recommendations

The data paint a complex picture of Maryland’s American Indian community. American Indian Marylanders are better off in several respects than their counterparts in other states, but too many still can’t access the education they deserve, afford basic necessities, or get health care when they need it. There are a number of steps policymakers can take to foster greater prosperity among American Indians in Maryland:

- Ensure that schools with the largest number of American Indian students have the same resources as all other schools. Quality education is critical to our economy’s future, but school districts with higher shares of American Indian students currently receive less adequate funding. One way to support quality education for American Indian students in Maryland is to ensure that all eligible school districts apply for federal Indian Education funding.

- Guarantee fair pay for hard work by expanding the minimum wage to cover more workers and raising it where the cost of living is highest. Workers who lack access to high-paying jobs benefit the most from a decent living wage.

- Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit. The EITC helps working families make ends meet, benefitting them, their communities, and the local economy. Children whose parents receive the EITC are healthier, do better in school, and make more money when they grow up.[viii] However, young workers and workers not raising children are largely left out of the EITC, which means they are taxed further into poverty.

- Provide adequate funding for job training programs across the state, and seek opportunities to maximize federal match funding. Job training programs have the potential to open career paths to American Indian Marylanders who are no longer in the school system.

- Fund culturally specific addiction treatment programs for American Indian residents. Although data on substance use in this population are not readily available, community members have expressed a need for greater support to American Indian Marylanders living with addiction.

- Hold insurers accountable. This year, health insurance companies in Maryland sought and obtained approval for large premium hikes on individual plans.[ix] Rising insurance costs threaten to put health coverage out of reach for more Marylanders, and communities that already struggle to access health care could be hit the hardest. Regulators should responsibly oversee insurers to prevent more rate hikes in the future.

[i] Unless otherwise specified, all data are 2010–2014 five-year estimates of the American Community Survey for Marylanders who identify themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native alone. “American FactFinder,” United States Census Bureau, last modified December 3, 2015.

[ii] “Graduation Rate: 4-Year Adjusted Cohort,” 2016 Maryland Report Card, last modified January 12, 2016.

[iii] MDCEP analysis of 2013–2014 MSDE data. “Final Calculations for the Major State Aid Programs for Fiscal Year 2014,” Maryland State Department of Education, last modified June 23, 2013. “ElSi tableGenerator,” National Center for Education Statistics.

[iv] ACS one-year estimates. Annual unemployment data for American Indian Marylanders show a similar pattern, but are not precise enough to distinguish true trends from statistical noise. “American FactFinder.”

[v] “Maryland Vital Statistics 2015 Preliminary Report,” Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, last modified September 2016.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] ACS one-year estimates. Annual insurance coverage data for American Indian Marylanders show a similar pattern, but are not precise enough to distinguish true trends from statistical noise. “American FactFinder.”

[viii] Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon Debot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, last modified October 1, 2015.

[ix] Kali Schumitz, “Will a Spike in Insurance Costs Slow the Progress Made Since Health Reform?” Maryland Center on Economic Policy, last modified September 16, 2016.