Supporting AAPI Marylanders Requires Stopping Hate Crimes and Removing Barriers to Opportunity

As a Filipina-American woman, my heart was shattered when I read about the six Asian women recently murdered in Atlanta and my mind continues to be in this overwhelmed state as more and more hate crimes continue to happen. First, I want to express condolences for all of the victims and their families affected by the shooting. Their deaths are personal and tragic. Second, I want to acknowledge members of the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community who are grieving, angry or upset. You are not alone in your hurt.

In this moment it is important to denounce hatred and physical violence against Asian Americans. According to Stop AAPI Hate there were roughly 3,800 reports of anti-Asian discrimination or harassment in the United States last year; 2,600 of the reports were against women. Another upsetting statistic suggests hate crimes targeting Asians have increased by nearly 150% between 2019 and 2020. While state data for 2020 has not been released quite yet, it is clear Asian Marylanders have been under attack: four Asian-owned Maryland restaurants were vandalized at the start of Lunar New Year, legislators made racist and sexist remarks within the General Assembly, and as members of Gov. Hogan’s family experienced discrimination. Anecdotally, it seems like in the past year these incidents have risen. My Asian American friends and family have shared stories about being glared at while walking outside or discriminated against in the workplace. A survey in February of this year found that 30% of Asian adults in Maryland reported feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge on more than half of days. Yes, we’re in the midst of a pandemic and many people are facing challenges, but for Whites this number was only 26%.

As a second-generation child of Filipino immigrants, I have struggled with a sense of belonging and the feeling of being seen. I was five years old when the first time someone pointed out to me that my skin color was different. They raised their arm next to mine to prove that I had darker skin. And in that moment, I looked up and realized I was one of very few who was not white. I spent the next 10 years of my life with the same classmates who made comments like, I was “only smart because I was Asian” or asked if my parents grounded me if I did not bring home a stellar report card. My experience as being the “whiz kid” is not entirely unique. These are symptoms of the “model minority” myth that perpetuates a narrative that Asian American children are geniuses, that Asian Americans are polite, submissive, and law-abiding, and that our families are made up of successful, rich doctors or lawyers. The myth persists because of Asian immigrants’ perceived successful adaptation to American life, but this is far from the truth.

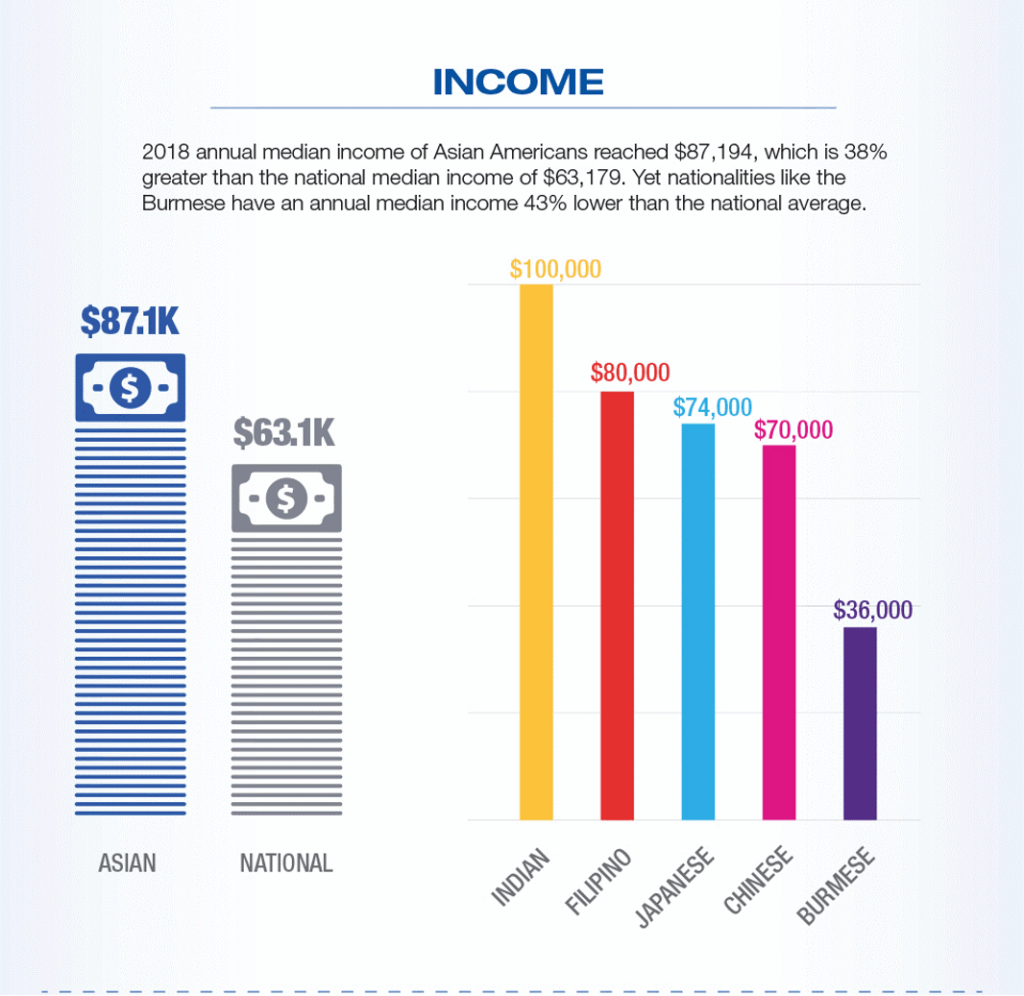

Viewing Asians as a monolithic and economically successful group erases differences among individuals and buries unique issues people of different Asian ethnicities experience. Doing so creates an issue for researchers and advocates as it masks the lived experiences of Asian Americans living on low- and moderate incomes. In fact, the model minority myth is often used to gloss over and fails to address the economic challenges many Asian Americans face. For example, in 2018, Indian Americans made about $40,000 more than the median income for all Americans, but Burmese Americans made about $30,000 below the annual median income. Collectively, Asian Americans made $24,000 more than the median income for all Americans. At the state level, the poverty rate for Asian Marylanders was 7%, compared to 9.2% for all Marylanders, and roughly equivalent to the white poverty rate. Yet 9.1% of ethnically Chinese Marylanders have family income less than the federal poverty line (currently $26,500 for a family of four), compared to 6.8% of white Marylanders.

Source: National Community Reinvestment Coalition

Analysis of 2018 annual median income of Asian Americans

The model minority myth has become a weapon, a “racial wedge,” within Asian American subgroups and other racial/ethnic minority groups, but especially for Black Americans. “If Asian Americans can do it, why can’t you” is a harmful attitude and stems from anti-Black racism. The model minority myth is not proof that if you work hard you can have the American Dream, and it most certainly should not dismiss the historical and present injustices faced by Black Americans. By reinforcing false narratives of race and success, we are thwarting our efforts to make the US equitable for all.

I was 21 the first time I learned about AAPI history or politics. As a Filipina woman, it was both an eye-opening experience to take a college class with an Asian American female professor, to learn about history of AAPI communities and to be surrounded by more and more classmates who looked like me.

We have heard about the famous Supreme Court cases such as Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade. But many have yet to learn about United States vs. Wong Kim Ark. Wong Kim Ark can be described as the father of birthright citizenship. Just recently, I discovered the first arrival of indigenous Filipinos, Luzon Indios, on the Nuestra Señora de Buena Esperanza to what is now known as Morro Bay in Upper California. Yet, the earliest memory I have of how members of the AAPI community were depicted in U.S. History class was as spies, foreigners and national threats.

Education has continued to cater towards the white perspective and reinforcing a perpetual foreigner stereotype. The anti-Asian bias is embedded into American history and still manifests today, like we saw when former President Donald Trump used fearmongering tactics by calling the coronavirus the “China virus” and the “Kung flu”.

We can do better and it starts by addressing the root causes of violence and the barriers that prevent Asian Americans from thriving. The long-term solution to violence is not increased police presence. We must continue to advocate for basic rights, economic opportunity and stability, increased access to mental health and physical care, and quality housing by working together to create a state where every person of every race or ethnicity can prosper. I and my colleagues at the Maryland Center on Economic Policy call on policymakers and everyday Marylanders to denounce the surge in anti-Asian racism, to improve their understanding of the AAPI community’s culture and history, and to not be a bystander in the face of injustice.

Resources for the Asian Community facing hate and violence:

- A list of local resources in English, Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese languages

- Mental health resources for the AAPI community

- A guide to community organizations serving AAPI in the DC metro area

- Local organization, Defend Yourself, is offering online trainings on Active Bystander Skills for Stopping Anti-Asian Hate

Resources to further engage in the AAPI Politics and History:

List originally created by Equity in the Center

- Long History of Racism Against Asian Americans

- How Racism and Sexism Intertwine to Torment Asian-American Women

- Asian American Women Are Resilient — and We Are Not OK

- Working for Equity and Social Justice? Know What Your Asian Colleague is Experiencing

- Critical Race Theory is not Anti-Asian

- It’s Time for Philanthropy to Address Its Erasure of AAPI Voices and Perspectives