Rent Is Rent: State Should Follow Baltimore’s Lead and Prohibit Landlords From Discriminating Based on Income Source

The Baltimore City Council last week considered a bill requiring landlords to treat federal housing assistance the same as any other source of income when evaluating rental applications. If the city adopts this bill, it will join a growing list of jurisdictions in Maryland and nationwide in prohibiting one of the most flagrant types of housing discrimination still allowed under federal law. This legislation will bring especially large benefits to people of color who, because of multiple historical and ongoing forms of discrimination, are more likely to have low incomes and more likely to rent their homes. It is long past time for the state to enact similar legislation.

More than 94,000 low-income households in Maryland are able to rent modest housing at an affordable cost thanks to federal housing assistance programs. These households include tens of thousands of children, aging adults, and people with disabilities. About 90 percent of households relying on housing assistance include a member of one or more of these groups. The bill under consideration in Baltimore would expand housing options for families that use Housing Choice Vouchers, which help beneficiaries afford rental housing on the private market. Housing Choice Vouchers are the most widely used form of federal housing assistance by a wide margin.

Currently, landlords in most parts of Maryland are allowed to pick and choose what kinds of income they will accept as rent. A landlord could say that income from a job is acceptable, but alimony isn’t—or that rent paid by a tenant’s parents is OK, but housing assistance isn’t. This causes a range of problems for families, housing agencies, and ultimately the entire community:

- Landlord discrimination makes it harder for people using vouchers to find housing. A study by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development found that a family would have to comb through up to 39 rental ads just to find one where vouchers are accepted. Finding a home that’s still available and meets a family’s specific needs could require sifting through many more ads—a process the researchers described as “time consuming and frustrating.”

- Landlord discrimination pushes families into high-poverty neighborhoods. The same study found that landlords in low-poverty neighborhoods were more likely to turn potential tenants away simply because they planned to use a voucher to pay part of their rent. This can leave families with no choice but to live in a neighborhood with limited food options, underfunded schools, and less access to good jobs.

- Landlord discrimination makes it harder for housing agencies to work effectively. The local agencies that administer federal housing assistance are authorized to issue a certain number of vouchers each year and are budgeted a certain amount of money to pay in rent. It’s up to them to use those resources effectively. When landlords reject a rental application, housing agencies must often reassign vouchers to another family or leave funds unspent—which can eat up staff time and reduce an agency’s impact.

- Landlord discrimination causes long-term societal costs. A large body of research shows that children who grow up in a thriving neighborhood are more likely to remain in good health, experience lower stress levels, succeed in school, and find a good job later in life. The benefits can ripple out to the entire community in the form of lower health costs and stronger economic growth. When landlords lock children out of these opportunities, we all pay the price.

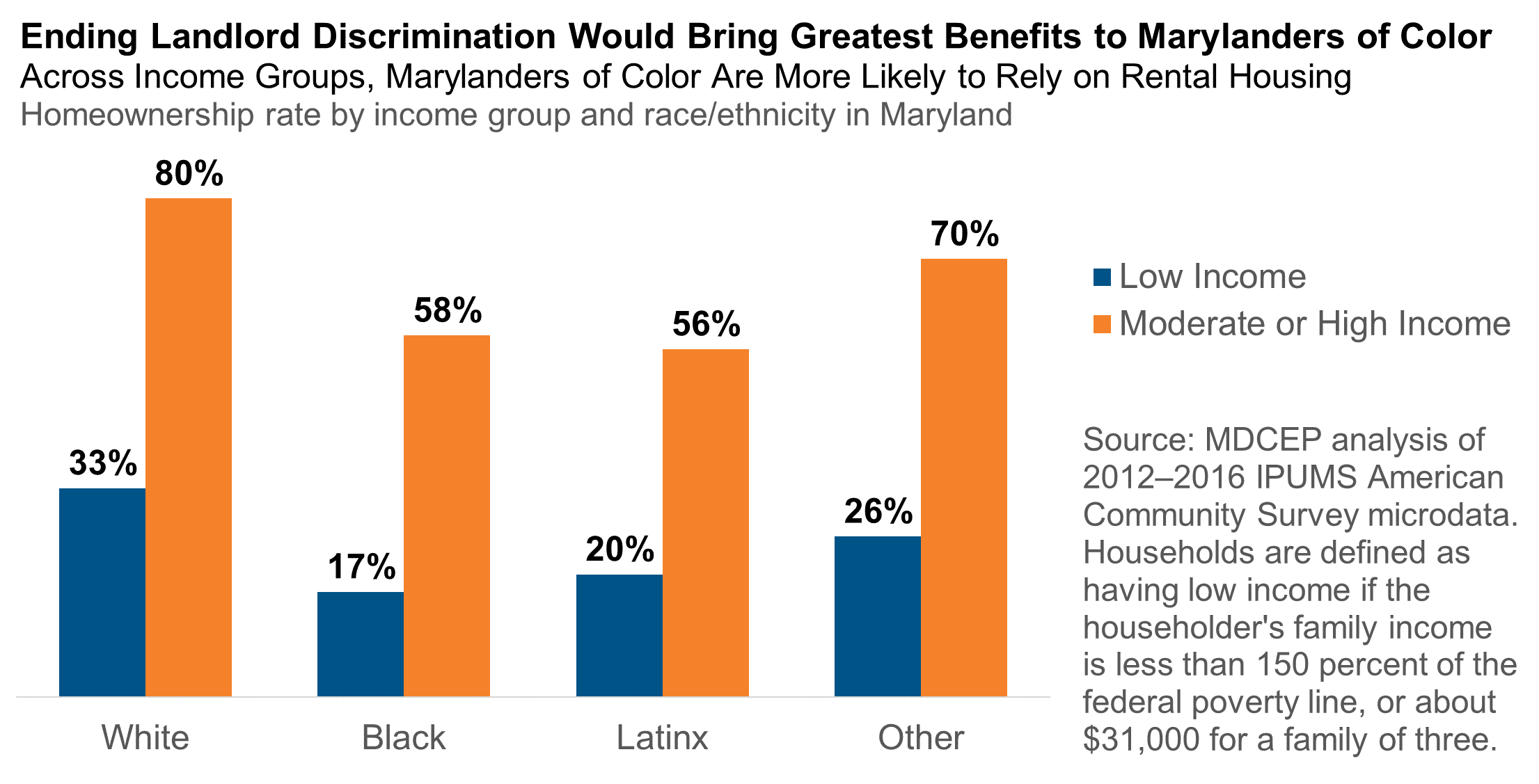

Moreover, the current policy of allowing discrimination is likely to hit Marylanders of color hardest, for two reasons. First, because of historical and ongoing policies that limit families’ access to good schools and good jobs, Marylanders of color are more likely to have low incomes. Second, the legacy of discriminatory lending and residential segregation has built barriers that make it harder for households of color to own their homes. This means that Marylanders of color are more likely to rely on rental housing, even in comparison to white families with low incomes. Meanwhile, our skewed wealth distribution means that the families with enough real estate and financial holdings to be landlords are overwhelmingly white.

There is a simple solution. The state should follow Baltimore’s lead and require landlords to treat all legal sources of income the same. This policy is already in place and working in Frederick County, Howard County, Montgomery County, and Annapolis—plus 10 states and the District of Columbia. Research shows that, while compliance is not perfect, landlords in jurisdictions with this requirement are more than twice as likely to consider potential tenants who benefit from housing assistance. Beneficiaries in these jurisdictions are also better able to access low-poverty neighborhoods and all the long-term advantages they offer.

The state should take two further steps to strengthen housing assistance. First, the state should invest in public education, monitoring, and enforcement to ensure that tenants know their rights and landlords fulfill their responsibilities. Second, the state should use its own resources to extend support to the thousands of struggling Maryland families who today pay high rent with no help at all, as the federal housing program only serves about a quarter of eligible families.