More Basic Assistance is Needed to Propel Economic Mobility and Security Among Maryland Families Receiving TANF

By Jasmin Aramburu

This report was supported by a grant from The Abell Foundation

When families go through a challenging period, income support programs are vital to helping them keep food on the table and a roof over their heads as they get back on their feet. The federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program helps families afford the basics when they are experiencing employment insecurity, sudden health complications, or other economic distress from personal or familial emergencies.

When the federal government created the TANF program as part of “welfare reform” in the mid-1990s, it gave states flexibility on how to support families that are struggling to make ends meet with the recognition that state financial participation is necessary for their success. TANF is currently financed through a fixed federal block grant that has not been adjusted since TANF’s inception, and through required nonfederal state dollars; the dollar amount for both sources is based on federal and state expenditures on welfare programs preceding TANF. Specifically, federal TANF funding may be used for four purposes:

- Providing assistance to low-income families so that children can be cared for in their homes;

- Promoting job preparation, work, and marriage;

- Preventing and reducing out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and

- Encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

In Maryland, the TANF core programs are cash assistance, known as Temporary Cash Assistance (TCA) and the job-training program, known as the Work Opportunities Program. TANF participants receive these benefits and services through the Family Investment Program.

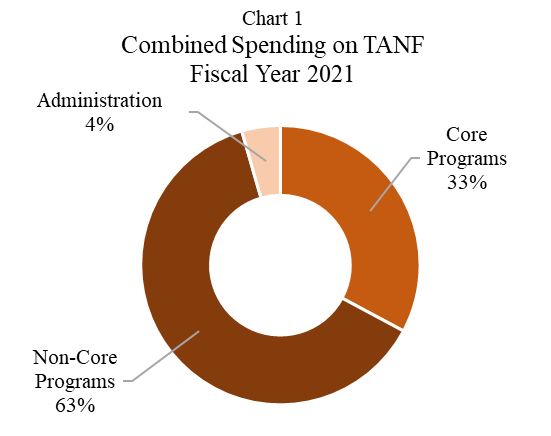

In recent years, Maryland has opted to use most of its combined TANF dollars on programs and services that are not part of its core goals of providing cash assistance to families so they can meet their basic needs, or helping parents find work. Today, these core programs make up only one-third of TANF federal and state spending in Maryland.

Maryland’s choices about where to use its federal and state TANF dollars show that the state is not investing as much as it can and should in core programming. It is clear that we need to expand the amount and reach of cash assistance to children and families most in need, particularly those who are living in deep poverty. This is especially important given that in 2021, 1 in 4 children in Maryland had parents who lacked secure employment, and almost one-third lived in households with a high housing cost burden.[1] TANF offers a critical lifeline of cash to low-income families, as well as crucial work supports to help parents find and keep good quality jobs. Both a comprehensive investment into core TANF programs and a holistic effort to improving such programs are essential to making sure no one is left behind.

Key RecommendationsBased on analyses and research on best practices, the report makes the following recommendations to maximize TANF’s potential to lift families out of poverty in Maryland:

|

TANF Families in Maryland

Before examining state expenditure trends on TANF programs, it is important to understand who is directly impacted by policymakers’ decisions on TANF spending.

Families

According to data from the University of Maryland School of Social Work, there were close to 28,000 families in an active TANF case in the state’s fiscal[2] year 2022.[3] Looking closer at the families:

- 96% included children receiving assistance

- More than half (53%) had children 5 years old or younger

- More than one-fifth (21%) were families in which only children were receiving benefits[4]

- 72% included one adult receiving TANF and 7% included two adults

- 1 in 8 families were new to the Temporary Cash Assistance program

Children

More than two-thirds (68%) of all Marylanders receiving TANF are children. Although it is evident that TANF primarily serves households with young children, the reality is that children of color are disproportionately affected by TANF program decisions and changes. Structural racism embedded within U.S. institutions and practices such as exclusionary labor laws, employment and housing discrimination, and social ideas deeming Black families as less deserving of support have contributed to present-day inequities that hinder socioeconomic mobility for Black families and other families of color. This history is reflected in Maryland’s racial makeup of TANF cases. The most recent available data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) show that out of the more than 39,000 children TANF served in federal fiscal year 2021, more than half (59%) were Black. [5] The remaining children were:

- 18% white

- 15% Multiracial

- 7% Latinx/a/o

- < 1% Asian

As extensive research shows, stable income contributes to better early childhood development and long-term outcomes for children.[6] For this reason, it would be incredibly significant for families in TANF to have additional cash support. Over one-third of children in TANF were 5 years or younger. The young demographics also explain why a substantial amount of children (42%) had no formal education.

Adults

Similar to the population of children receiving TANF, most adults receiving TANF in Maryland are Black. In the state fiscal year 2022, about two-thirds (67%) of adults participating in Maryland’s TANF program were Black, with the rest being:3

- 22% white

- 4% Latinx/a/o

- 6% another race

Although most (78%) adults completed at least a high school or equivalent education, about 22% did not finish high school. Generally, the more education one has the better prospects for income and employment.[7] However, because many of the adult recipients are people of color, they are also more likely to face discrimination and other structural barriers to employment and a better education. Redesigning the Work Opportunities program and actively dismantling employment barriers in Maryland can help meet the need for increased job preparation and work supports.

In terms of employment, the majority (55%) of Maryland adults in TANF had a job before they began receiving cash assistance, though this is not indicative of how many adults maintained employment (whether the same of different job) while receiving benefits in the state’s fiscal year 2022.[8] However, according to federal HHS data, about one-fifth of adults in an active TANF case in Maryland were employed in federal fiscal year 2021, a slight but higher share when compared to the national average for an adult in TANF.

The harmful and racist narrative that families receiving TANF—specifically Black women—are willfully and irresponsibly dependent on public assistance has shaped welfare policies and outcomes for many families.[9] These ineffective and harmful policies include TANF time limits that cut off families from assistance; increased work requirements that do not match parents’ needs, skills, or experiences; family caps limiting assistance if a parent has additional children while on assistance; low benefit levels that do not take into account cost of living adjustments; drug testing; resource limits; and the overall controlling and punitive nature of the program that imposes sanctions when families cannot meet the requirements. This racist legacy within current welfare programs can be traced to 20th century cash assistance programs encouraging the belief that a mother’s behavior and character defines their deservedness for support, often leaving unwed and Black mothers out of aid.[10] Due to their occupations, many Black working women were also often excluded from various safety net programs like unemployment insurance and what is now known as Social Security. Today, TANF promotes core values of personal responsibility that are based on biased assumptions and limit many families from seeking assistance.

People do not want to find themselves in a situation in which they need cash assistance, which is why we need to do all we can to ensure that people who are experiencing temporary and longer-term economic distress can access cash assistance quickly with flexible program rules, and ultimately find employment that provides enough resources to support their family. Based on state fiscal 2022 data, about two-thirds (65%) of families receiving TANF did so for 24 months or less in the past 5 years, with 16% who had never received cash assistance and 21% who only received it 1 year or less.3 Additionally about 16% of families were near the federal time limit of 60 months.

TANF Spending in Maryland

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

|

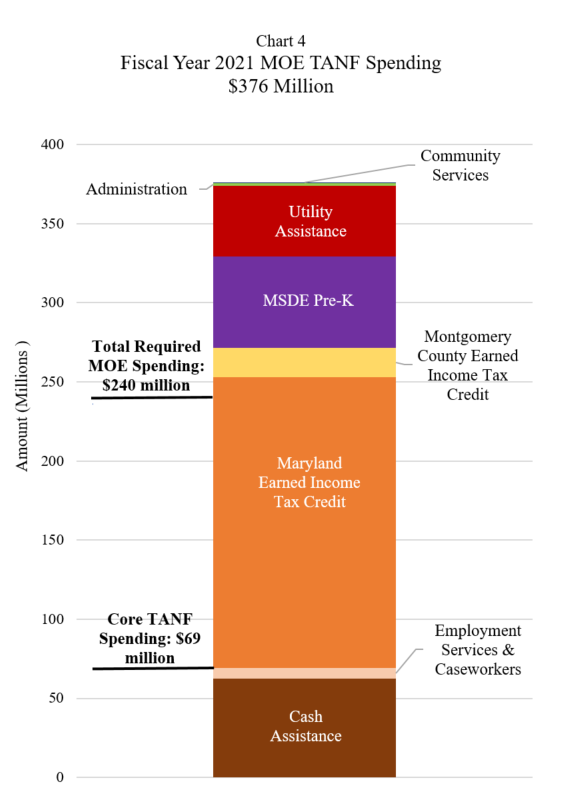

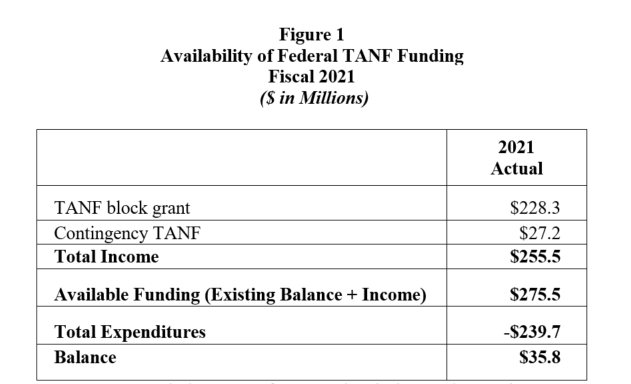

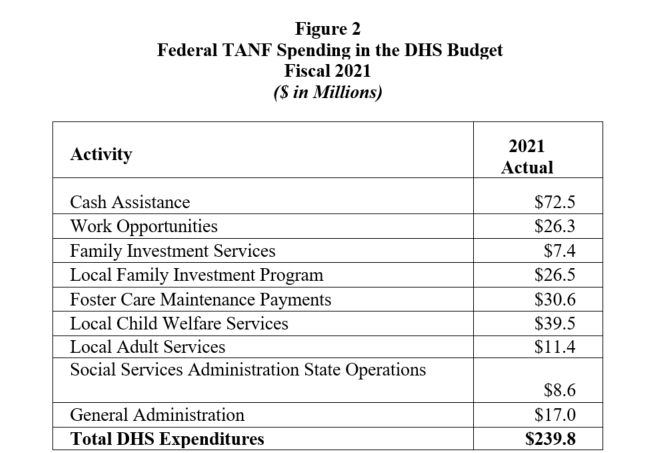

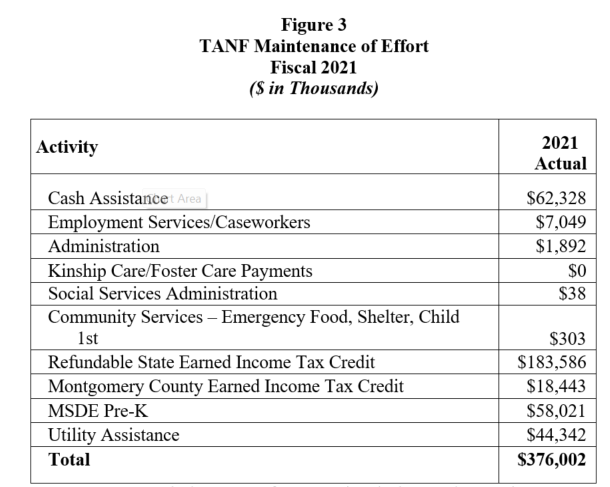

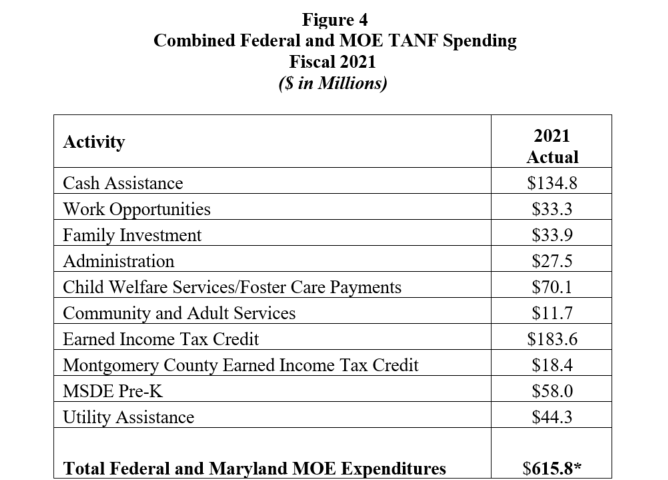

TANF funding structures include both federal and state funding streams. The federal government block grant, known as the State Family Assistance Grant, funds Maryland’s TANF program at $228 million per fiscal year. The block grant, set at $16.5 billion for all states, has remained unchanged since 1996 and therefore lost its value by more than 40% despite changes in demographics and population growth.[11] This current funding structure disproportionately harms families of color as states with higher numbers of Black children tend to receive the least amount of funding per child.11 States are also required to spend a certain amount of state revenue on TANF programs, known as the Maintenance of Effort (MOE). This amount is based on the state’s share of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the program that preceded TANF. Importantly, states are allowed to spend more than their MOE requirement. In fiscal year 2021, Maryland spent $616 million[12] in state and federal funds attributed to TANF (see Appendix). This included some of the state’s $228 million federal block grant, an additional $27 million in federal contingency funds,[13] and $376 million in state MOE expenditures.

Combined Core Spending

In fiscal year 2021, Maryland spent only 33% of its combined[14] TANF dollars on core programs.[15] Most of the core spending is for Basic or Cash Assistance (22% of combined TANF spending), followed by the Work Opportunities program (5%), which are operated through the Family Investment Program[16] and its related services (6%). Child care is also a core programming category that many other states include as part of their core spending. Although it appears that Maryland did not spend any TANF federal or state funds on childcare, other federal reports suggest that less than 1% of TANF funds have gone to childcare.[17] It is important to note that while Maryland TANF spending on childcare appears nonexistent in budget analyses from the Department of Human Services (DHS), this is largely due to the fact that the Maryland State Department of Education, not DHS, handles funding for early childhood services including the Child Care Scholarship program, which greatly benefits and prioritizes families receiving cash assistance.

Combined Non-Core Spending

Maryland spends the majority of its combined TANF dollars in non-core programs (63%). The state refundable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Montgomery County Working Families Income Supplement make up the largest portion at 33% of total funds, though the credits are solely funded by state or county dollars. Although Montgomery County’s income supplement is funded from county not state dollars, the state is still able to count it as part of its MOE requirement when reporting TANF spending to the federal government on the technicality that the county has residents who benefit from cash assistance. The remainder of the combined TANF spending is spent on child welfare/foster care payments (11%—though funds were solely federal), pre-kindergarten programs (9%), and various social service programs, including community and adult services (2%), and utility assistance (7%).

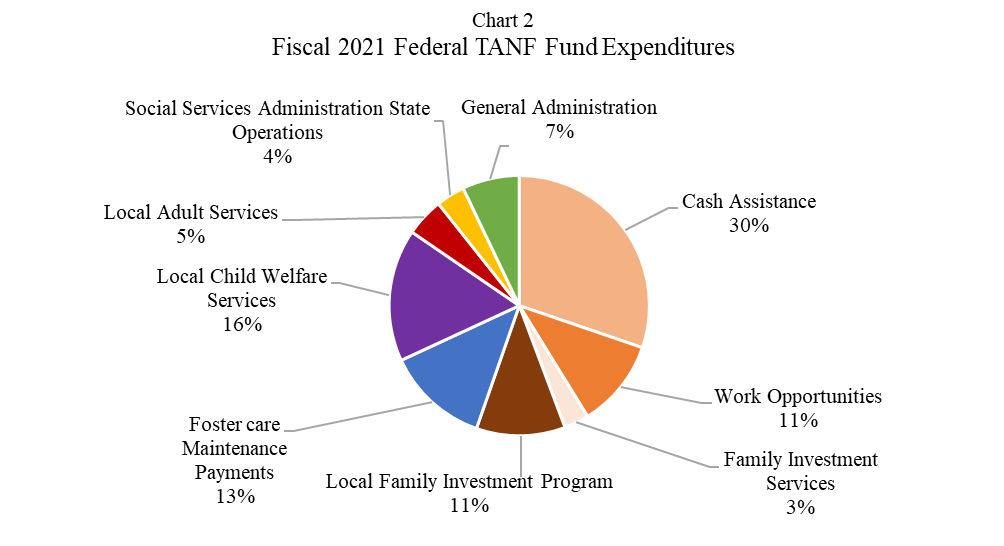

TANF Federal Spending

Per state budget documents, Maryland used a total of $239.8 million in federal TANF funds for fiscal year 2021. According to data reported to the federal government, total expenditures from federal funds for TANF programs and services amounted to $217 million with the remaining $23 million transferred to the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG), which is used for programs and services to children or their families whose income is less than 200% of the official poverty line (as defined by the Office of Management and Budget).[18] A state can transfer up to 10% of its TANF funds to the SSBG. Based on 2020 federal data, it appears that Maryland uses most of the transferred funds to offset state costs for foster care and protective services for children.[19]

The state spent 55% of its federal dollars in Cash Assistance, the Work Opportunities program, and on the Family Investment Program and related services. The remaining 34% of federal TANF dollars are spent in non-core areas, such as Child Welfare/Foster Care (29%), and Local Adult Services[20] (5%). Administrative and Operations support make up 11% of expenditures.

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

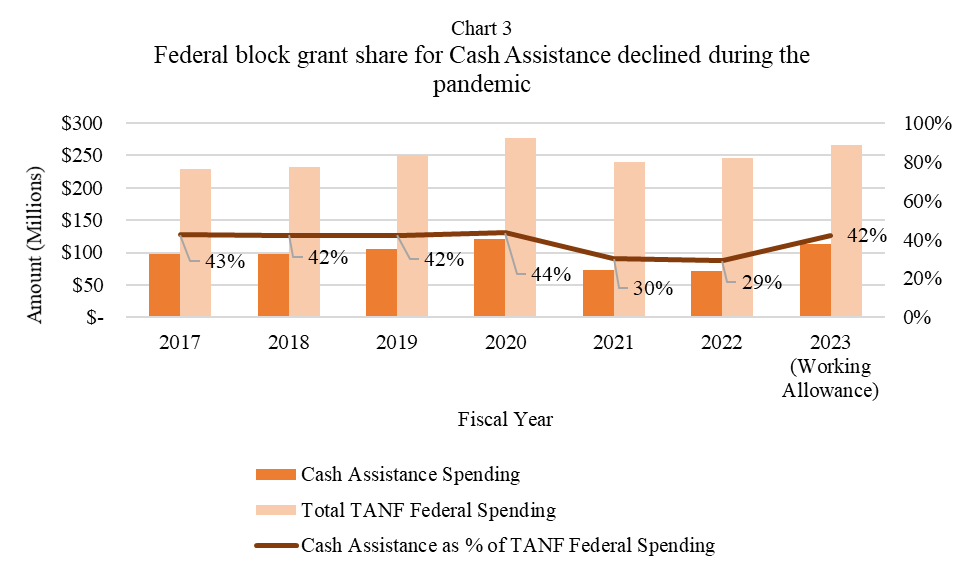

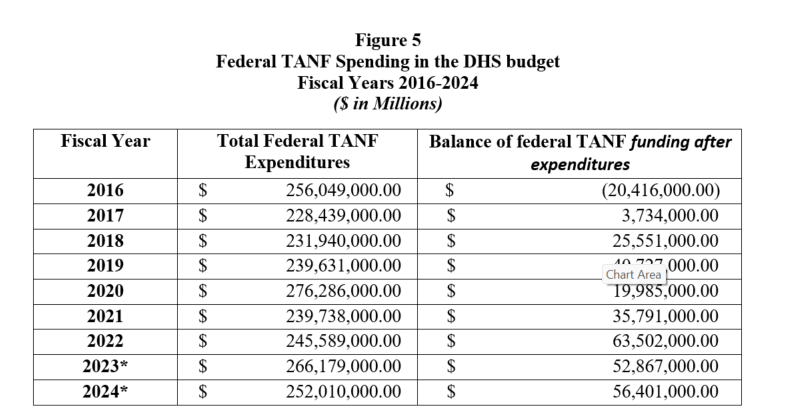

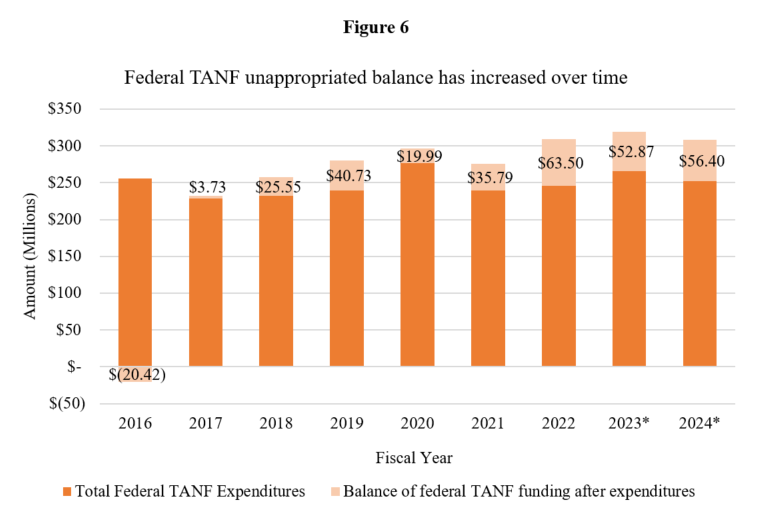

Chart 3 demonstrates a decline in cash assistance spending as a share of the federal TANF block grant. Notably, the Department of Human Services swapped usual federal TANF funds for State Fiscal Recovery Funds made available through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 due the economic crisis from the COVID-19 pandemic. The basis for the swap was to assist the state with higher TCA caseloads and thus reduce TANF spending, leaving the state with $35.8 million in available TANF block grant funds at the end of the fiscal year.

|

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal Budget Overview Documents 2018-2024 |

Based on actual spending for fiscal year 2022,[21] it appears that not only is there an increase from fiscal year 2021 in the federal TANF unspent balance,[22] but it is estimated to continue for both fiscal 2023 and 2024, albeit smaller than 2022 (See Appendix, Figures 5 and 6). Data from actual fiscal year 2023 spending is not yet available. Although a surplus is beneficial when accounting for unexpected or even foreseeable economic downturns, the state should ensure that TANF families will continue to see improved services, such as a higher cash benefit, with the remaining balance.

Maryland MOE Spending

Maryland’s MOE spending in core and non-core TANF areas varies significantly from the state’s federal spending, in part due to differences in requirements for spending and the state’s decisions of what to count under its MOE. In FY 2021, Maryland spent $376 million to meet its TANF MOE obligation. Cash Assistance (17%) and Employment Services (2%) were the only core spending under the MOE, a total of 19%. The majority of spending, 81%, was in non-core programs and services. Administration costs made up less than 1% of spending. MOE non-core expenditures include pre-K programs (16%), utility assistance (12%) and community services programs and services (less than 1%). No state MOE funds were used for kinship or foster care payments in FY 2021.

|

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview |

The refundable Earned Income Tax Credit, including Montgomery County’s Working Families Income Supplement, a match of the state EITC, make up over half (54%) of the primary MOE spending areas. In federal fiscal 2021, 16 states (including Maryland and the District of Columbia) reported expenditures from their state EITC as part of their MOE spending.18 However, the EITC accounted for more than one-fifth of states’ MOE spending in only 5 states, and more than one-third in two states, one of which was Maryland. The national share of spending on refundable tax credits for MOE, whether EITC or non-EITC, was 9%.[23]

Although considered a non-core spending area in the TANF program, the refundable Earned Income Tax Credit is a proven and powerful tool that provides a much-needed economic boost to Maryland’s working families. From covering emergency or one-time expenses to supplying families with funds to cover everyday essentials such as diapers, food, or even housing costs, the EITC can help families stay afloat in today’s economy where inflation is still higher than in pre-pandemic levels.[24]

The passage of the Family Prosperity Act this 2023 legislative session was a great step towards ensuring continued support for thousands of Marylanders by making permanent previous expansions to the EITC. These expansions include:[25]

- Increasing the average state credit to $1,100, benefitting more than 400,000 Marylanders

- Authorizing more than 90,000 workers, not claiming dependents, eligible for a maximum credit of over $500—more than they were previously eligible for—and increasing such credit with inflation

- Making more than 100,000 immigrant taxpayers eligible for the credit, so far benefitting 30,000 to 40,000 newly receiving households per year. This is particularly significant given the limitations on the use of federal TANF funds for persons without qualifying immigration status

While the state EITC is a powerful and important counterpart to the state’s cash assistance programs, it may not reach many of the families the TANF program is designed to serve. If someone is not currently working, underemployed or unable to work, as is the case with many adults in TANF, they will not benefit from the EITC.

It is because of the compelling evidence[26] of the success of strong safety net programs at mitigating economic hardship, primarily by putting more dollars into low-income and working families’ hands, that makes it essential for Maryland to increase and sustain cash assistance for families. Elevating the appropriation of funds for direct cash assistance will increase economic security and purchasing power among marginalized communities and ultimately help boost local economies.

Overall, MOE spending increased by $107 million between FY 2020 and FY 2021 due to increases in cash assistance resulting from higher caseloads during the pandemic and from program expansions in the state EITC. The state also exceeded its MOE spending requirement by $136 million in FY 2021 and is expected to continue this trend in subsequent years.

How States Can Meet MOE RequirementsTo meet MOE requirements and receive the federal TANF block grant, states are expected to spend 80% of the amount of nonfederal funds that the state spent in federal fiscal year 1994 under TANF’s predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and related programs. Congress has not adjusted this requirement for inflation and therefore its value has declined over the past nearly three decades. If the requirement was 100% (~$236 million) and was adjusted for inflation in today’s economy, Maryland would be required to spend at least $486 million annually.[27] Furthermore, if the state meets its Work Participation Requirement (WPR) the MOE requirement is reduced to 75% of the state’s historical expenditures. Yet states can and do spend more than their required spending in order to either access additional federal funds or to help meet the federal work participation requirement. Because Maryland accessed an additional $27 million in contingency funds, it was required to spend $240 million in state dollars in FY 2021. Maryland counted $376 million toward its MOE spending in FY 2021. Under AFDC, Maryland’s state spending went entirely to what are now known as core programs and administration services. Today, Maryland’s spending is contributing much less to the core goals of the program. Fiscal 2021 MOE spending on core and administration costs was only just over $71 million or 19% of total MOE funds. Maryland meets and exceeds its MOE requirement by counting spending on other programs such as the EITC and pre-K programs. In order to count certain expenditures as part of a state’s MOE, the spending must be for eligible families defined as families in which a child lives with their custodial parent or an adult caretaker, or a pregnant woman, and who meet income eligibility criteria established by the state.[28] The allowable purposes for which spending count toward a state’s MOE requirement may include:

The expenditures must also follow a “new spending test” that determines the amount a state must spend on a program to count towards its MOE if the program or service existed in federal fiscal 1995, in addition to other restrictions. [29] In-kind contributions or expenditures by nongovernmental third parties may also be counted towards a state’s MOE (though there must be an agreement between the organizations and the state permitting the state to count the spending towards their MOE requirement).[30] An example would be volunteers’ time, though services or benefits provided must be for eligible families and those that usually count toward the MOE. It is possible that Maryland has other current qualifying MOE-related expenses that are not included in expenditure reporting. Because MOE or state funds are more flexible than federal dollars, they can be used to assist two additional groups (aside from those that usually qualify for federally funded benefits):

Lastly, a state may choose to combine their dollars with federal funds to finance TANF services, or choose to spend their funds separately in another program or just have their funds accounted for separately.[31] If they choose to combine their funds, all requirements and restrictions under the federal government will apply uniformly. However, if the state chooses to spend their money separately from federal dollars, then applicable requirements will depend on whether the state counts services under MOE expenditures or under a solely state-funded program. |

Maryland’s TANF Core Spending

To help improve the lives of low-income families, it is crucial that Maryland invests more of its TANF dollars in core programs such as cash assistance, supports that enable participants to gain employment, and to boost its child care system. Today, TANF reaches a very small share of low-income Maryland families, a sharp contrast from AFDC, which reached nearly all low-income families in the state. Much of this resulted from the implementation of harsh work requirements and time limits which primarily impacted Black families and other people of color. In 1995-1996, AFDC cash assistance reached 97 of every 100 families living in poverty in Maryland. In contrast, in 2019-2020, TANF cash assistance reached only 29 of every 100 Maryland families experiencing poverty—a 68-point difference that is much higher than the drop at the national average.[32] It is important that the state invest in core TANF areas to help families gain stability until they have jobs that pay sufficient wages to support a family.

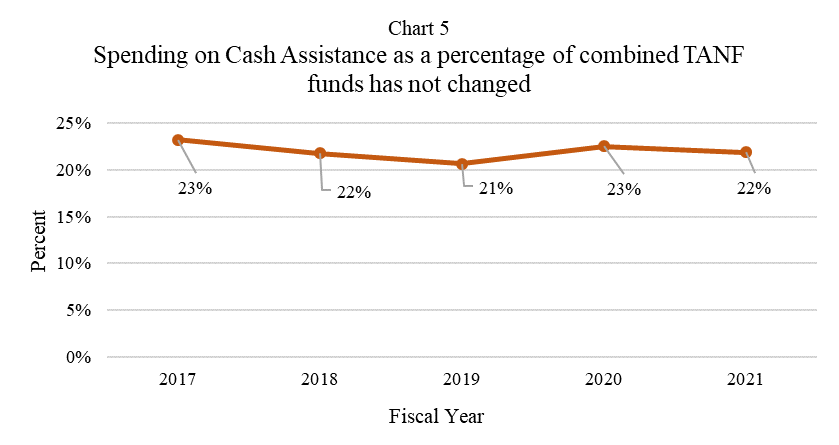

Cash Assistance

Maryland only spends 22% of its combined TANF funding on cash assistance. Even with the addition of COVID-19 relief money from the federal government to combat economic uncertainty and an increase in state dollars being used for cash assistance in fiscal 2021 compared to previous years,[33] we see (Chart 5) that spending on cash assistance as a percentage of combined TANF (non COVID-19 money) expenditures has remained at 23% or below. If we want to provide families with the most meaningful tools to reduce poverty, we need to invest much more into basic assistance.

|

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal Budget Overview Documents 2018-2024 |

The maximum benefit—which is usually given to families with little or no income—of $727[34] per month for a family of 3 people only meets 35% of the federal poverty line for that family size.[35] The amount barely scratches the surface of what is needed to support a family in today’s economy and thus keeps families in deep poverty. The high costs of living in the state further point to the need for stronger support. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, fair market rent,[36] which includes rent and core utilities, for a two-bedroom apartment in Maryland is $1,616. A family would have to make roughly $5,387 monthly or $64,642 a year to afford such rent while spending no more than the recommended 30% of their income on housing.[37] It is thus no surprise that Maryland is the 10th most unaffordable state in which to live. In Baltimore City, which has the highest amount of TANF families in the state, the annual income needed to afford a two-bedroom is $61,920, or $1,548 per month. This means that a household would need more than two full-time jobs at the current minimum wage to afford a two-bedroom apartment.

Looking at the whole of typical family costs, one parent with two children living in Baltimore City would sustain monthly average costs of $5,629 for basic living expenses such as housing, food, transportation, health care, child care, and other necessities, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This amounts to annual expenses of $67,547.[38] These calculations are based on 2020 dollars and therefore do not reflect the additional financial strain produced by rising living expenses and inflation to families over the last few years. Expenses of $5,629 in 2020 would be equivalent to $6,662 in 2023, due to inflation.[39] While TANF families often benefit from additional resources such as the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps), the amount of cash needed to have an adequate standard of living is far beyond the current allotted amount.

In recent years, both former Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan and current Gov. Wes Moore have included additional funds in their budgets to increase benefits for cash assistance by $100 per person per month between January 2021 and April 2022, and most recently $45 per person per month beginning September 2022. However, the supplements have not been made permanent in statute and still fall short of families being able to meet their basic needs. Increasing our investment in cash assistance would greatly benefit families in securing housing, buying basic essentials, and would help them reinvest in their local communities.

Unlike most other states, Maryland’s benefit amounts are supposed to somewhat keep up with inflation due to a law[40] that requires the governor to ensure that the value of cash assistance, when combined with SNAP, is equal to at least 61.25% of the State Minimum Living Level.[41] Even then, it is only a portion of what is determined to be the minimum level needed to make it through and is calculated with the addition of food benefits not cash alone. The cash benefit amount has not increased since October 2019 despite efforts from advocates (with the exception of the additional funds aforementioned), in part due to the increases to the SNAP benefit, thus cash assistance has not kept up with recent changes in inflation. As of 2022, Maryland ranked 9th when assessing all states’ TANF benefit levels as a percentage of the federal poverty level, or comparatively better than most other states.[42] A couple of the states that rank higher than Maryland have adjusted their benefit level so that it accounts for at least 50% of the poverty level for a family of three.

Elected officials around the country are starting to understand the benefits of direct cash transfer programs in combating poverty and income disparities among marginalized groups, often comprising communities of color. Jurisdictions across the country, including several in Maryland, have implemented guaranteed basic income pilots, which are programs that provide recurring cash payments to a specified group of people based on a range of eligibility criteria, without the punitive and cumbersome restrictions in the TANF program that often deter families from seeking and receiving assistance. Uniquely, Philadelphia is the first place to use existing TANF funds towards a 12-month guaranteed income pilot program that provides additional cash payments to TANF families that have extended their participation beyond the 60 month federal limit.[43] This opportunity has the potential to create immense change for the participants who, for a number of reasons, are unable to secure full-time employment even after actively participating in work programs. The program design will provide 50 people who have received extended TANF benefits an additional $500 per month, and this group will be compared to another 250 recipients who will receive an additional $50 per month.

Through programs like Philadelphia’s 12-month guaranteed income pilot, we can ensure that funding for cash assistance will reach a larger pool of families that need it the most. An even greater step would be for state-level cash assistance programming to be modeled after guaranteed income programs that have less restrictive mandates and eligibility criteria. Doing so can move the state towards undoing some of the adverse effects of dehumanizing policies that have resulted in a low percentage of families eligible for TANF actually receiving it.

Although not part of formal cash assistance for TANF recipients, other states have also taken the initiative—whether legislatively or administratively—to include increased supplemental benefits or non-recurrent short term payments for items like diapers and other child-related necessities in the past year.[44] For example, Oregon provided $270 per TANF family for clothing allowances three times a year (at the beginning of school, in the winter, and in the summer), and D.C. appropriated funds to create a diaper bank program to assist families who qualify for TANF or other income-based programs.[45] Non-recurrent short-term benefits are excluded from the definition of assistance and not subject to the federal TANF requirements since they are:

- Designed to deal with a specific crisis or episode of need

- Not intended to meet ongoing needs, and

- Not to be extended beyond 4 months

Several states have also introduced additional housing supplements or allowances for families in TANF to better afford housing costs.[46] Many of the families receiving TANF are likely to also qualify for housing assistance programs but due to deeply inadequate funding of housing assistance programs, many who are eligible do not qualify. As a result, many TANF families are faced with housing insecurity and homelessness. Some of the housing supplements in other states are as little as $40 a month to more meaningful amounts of up to $500 a month.

Work Opportunities

In fiscal year 2021, Maryland spent 5% of its combined funding on the Work Opportunities program. According to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services18 Maryland is one of 22 states that spends 5% or less on work activities, though the national average spending is 8%.23 The Work Opportunities program is intended for parents to get the job training skills needed for employment. According to the most recent University of Maryland School of Social Work’s Life After Welfare report, while adults’ median earnings after exiting TANF generally increase over time (around $12,000 in their first year after exiting compared to $19,000 in year five), the earnings remain very low and thus many families in the state continue to live in poverty and deep poverty.[47] In fact, low wages are common for former adults in TANF as they tend to work in low-paying industries such as administrative and support services or food services. It is important to note that earnings for former recipients that transition to full-time employees tend to be higher than those who are not employed full-time. It is critical that the funding for work activities serves to create and support high-quality job training programs that help parents get jobs with family-supporting wages.

Understanding the connection between well-equipped work programs and successful outcomes, Maryland lawmakers passed House Bill 1041 in 2022, which requires DHS to conduct annual reviews for their nongovernmental contractors that offer work programs to assess overall program impact such as:

- The number of parents enrolled in education or training programs that build skills and measure progress toward employment

- Measure employment outcomes for families who left TCA due to increased earnings

- Assess the number of recipients who experienced housing insecurities including homelessness while participating in work activities

Additionally, DHS must hire an external consultant to review the Family Investment Program to assess how it is meeting and implementing program goals, and to look at best practices in other states. The review is a step in the right direction towards understanding the changes needed to improve work opportunities for TCA recipients. It is also an opportunity for Maryland’s TANF programs to become a model for other states – but it is essential that reforms come with sufficient financial commitment to make the program a success.

Childcare

Access to high quality and affordable childcare is also essential for families to sustain employment and achieve economic security. During the height of the pandemic, we saw parents struggling to keep up with childcare needs due to access challenges, waitlists, or lack of available child care centers/providers as many closed temporarily and sometimes permanently. Many of these issues were already part of shortcomings in the child care system that were only worsened at the time. Many parents continue to lack enough income to cover the rising costs of care even as they return to employment. In fact, parents have consistently listed cost as the number one reason why they cannot find childcare in Maryland.[48] In 2021, the average annual cost of center-based childcare was $11,090 for toddlers in the state.1 Single parents are disproportionately impacted, particularly single mothers. The average annual cost of childcare amounts to one-fourth (25%) of a single mother’s median income compared to 8% of a married couple’s median income. As a result of childcare challenges in 2020-2021, 12% of children’s families experienced job changes or problems, with Black and Latinx children more likely to be affected.

Maryland’s Child Care Scholarship program—a financial assistance program that provides childcare tuition to low-income families—is primarily funded though federal allocation from the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) within the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE). According to analyses from MSDE, state general funds for the Child Care Scholarship program have increased since fiscal year 2021.[49] However, an estimated $96.3 million in supplemental federal funds made available through ARPA remained unappropriated. Consequently, lawmakers decided to replace $10 million in state funds initially budgeted for fiscal year 2024 with federal funds.

The 2023 legislative session was successful in making improvements to the Child Care Scholarship program such as eliminating waiting lists and reducing or eliminating co-payments for families. We should continue to build on this momentum to revitalize and strengthen childcare services in the state. Relevant stakeholders should also continue to have an input on the allocation of the remaining federal funds for childcare assistance, ensuring those funds are adequately and equitably spent.

Changes resulting from the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023

Recent federal changes to the TANF program will require some states to increase the number of people who must meet work requirements, a practice that is based on punitive approaches to welfare reform and is ineffective in getting people the help they need. Maryland did not meet its all-family work participation rate requirement in federal fiscal year 2021 due to temporary changes in the work requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. Attributing the low levels of participation in work requirements due to their suspension at the height of the pandemic, DHS was reportedly in the process of applying for a good cause waiver as to not get penalized.[50]

While federal policy changes will require Maryland to carefully plan how the state engages parents receiving cash assistance, it must do so by keeping in mind recent state policy changes meant to improve and humanize the work programs. For example, Maryland lawmakers passed House Bill 1043 in 2022, which placed restrictions on the use of unpaid work experience and community service to fulfill work activity requirements such that a person can only be placed in this program once for a maximum of 90 days within a three-year period. It also requires DHS to make it clear that unpaid work experience is a choice for parents. Moreover, the unpaid experience must match the individual’s personal, career, and family goals, and DHS must inform parents that they can switch to a different activity.

Policy Recommendations

Lessons from the pandemic have taught us that a strong social safety net is fundamental to keep families afloat when encountering economic crises, whether on a personal or macro-economic level – and that such policies that reduce poverty provide powerful benefits to families, communities and our economy. Maryland should ensure state supports for families largely align with their needs. The following recommendations can be a starting point towards shared prosperity in the state:

-

Increase the share of TANF dollars for basic/cash assistance

Maryland can be a state with opportunity for everyone if we make sufficient investments in programs and services that support all families. It is vital that Maryland prioritizes core TANF areas by appropriating a larger share of funds specifically for cash assistance. Although the state spent more on basic assistance than the national average in federal fiscal 2021,23 14 states spent a higher percentage on basic assistance from their combined TANF dollars, including neighboring D.C. and West Virginia.18 Direct cash allows families to have more flexibility in spending for a variety of needs, rather than assistance that is restricted to certain expenditures that do not always take into account the complexity of life challenges. Based on budget analyses from state documents, it is clear that Maryland is able to provide more cash to families through a larger appropriation in federal funds. As of 2022, Maryland accumulated $63.5 million in unspent federal TANF funds, much of which could be used for additional cash assistance. Diverting funds from other programs (more explained in recommendation #4) towards cash assistance can also help finance an increased benefit level. For example, not all allowable spending purposes under TANF require money to be spent on families with limited income. Unlike TANF’s first two core purposes, spending for purposes 3 and 4—meant to prevent out-of-wedlock pregnancies and help maintain two-parent families—can be used for families that are not defined as “needy” by the state, thereby taking funds from families going through financial stress. By diverting these funds towards cash assistance we can ensure that the money is spent on lower-income families.

Moreover, while it appears that Maryland is a generous state by exceeding its MOE spending requirement, it is masked by the fact that cash assistance and job preparation only make up less than one-fifth of state spending on TANF. Maryland needs to reverse this trend by ensuring that most of its state dollars for TANF is going towards basic assistance. We can be more confident that state revenue for TANF is equitably appropriated by requiring the state to be more transparent when it is making MOE spending decisions and through more detailed public budget documents.

-

Allow full pass-through of child support and disregard for TANF families

As a requirement of receiving TANF, families are required to cooperate in establishing child support cases, if applicable.[51] Families must also resign those payments to the state and the state is permitted to keep the money to reimburse itself and the federal government for TANF services. However, states may also choose to allow some of the child support to pass through to the families and may disregard that income when determining eligibility for TANF. Maryland’s current pass-through policy—which began in June 2019—allows the first $100 in child support to pass through for one child and $200 for two or more children, and disregards such payments when determining income eligibility.[52] Since then, many families have benefitted from the additional income in their homes. Between August 2019 and March 2020, families receiving TCA received over $2 million in pass-through support.52 On average, these payments increased recipients’ quarterly income by 11%. The percentage of families receiving any income from child support also increased from 10% to 49%.52

While this was a great step for Maryland, we also know that we can do more to ensure that families are receiving the full amount for which they are entitled. Wisconsin takes a different approach in that rather than setting a fixed amount for pass through, it sets a percentage (75% in their case).51 However, the best models come from California and Colorado as they are the only states that will allow or currently allow a 100% child support pass through and disregard. Maximizing opportunities for families to receive additional income will only improve their chances at success.

-

Ensure that the Work Opportunities program is participant-centered, equitable, and anti-racist

Maryland should ensure that its Work Opportunities program does not follow the punitive and ineffective legacy of the federal work requirements but rather strive to create an environment where participants feel supported and encouraged about employment prospects. A well-designed program will:

- Successfully transition TANF recipients to full-time employment, where applicable

- Help families earn competitive wages

- Provide opportunities for upward mobility

- Center participant needs and professional goals

- Practice a collaborative and empowering framework

- Identify and address discriminatory labor practices that disproportionately impact workers of color

- Provide broad and flexible exemptions from the work program to support families when they are unable to work

Vermont’s recent changes[53] to its work programs, which shift the focus from meeting the federal work requirements to helping participants achieve their professional, personal, and familial goals, is a great model that Maryland can follow. Specifically, the changes replace the traditional 12 work activities that count towards meeting the work participation rate to a list of activities that focus more broadly on financial stability, education, and addressing employment barriers.

Maryland families would also benefit from programming that is more flexible and understanding of life changes. Instead of trying to get recipients to comply with work requirements as quickly as possible, agencies should allow ample time for participants to get their housing and other needs situated. Parents will be better prepared to participate in work programs and more likely to be successful if they can focus on work tasks rather than thinking about where they will sleep. For example, Maryland can extend its current six-month exemption for families new to TCA to 24 months, per federal guidelines, which assert that states may engage people in work requirements whenever the state determines the parent to be ready or if they have received assistance for 24 months.[54]

-

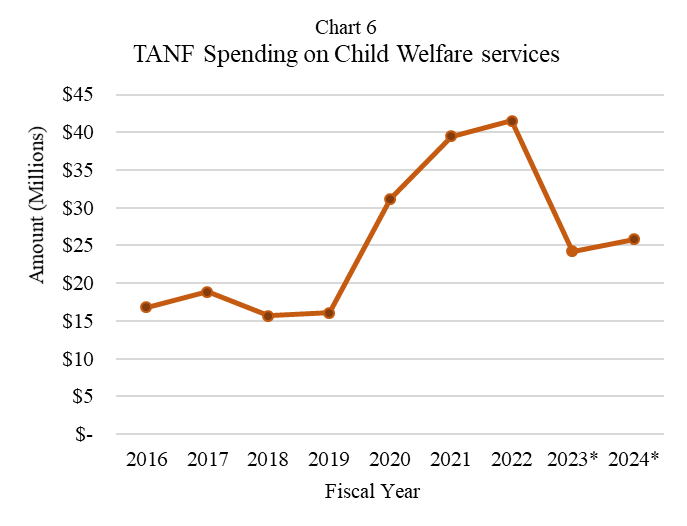

Divert TANF funding from Child Welfare services towards Cash Assistance

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal Budget Overview Documents 2018-2024 * Do not reflect actual amounts, just appropriations or allowances for those years |

TANF funding for child welfare services would be better directed towards basic assistance, particularly considering the role child welfare programs have played in disproportionately harming communities of color. Historically, Black and American Indian children have been more likely to be involved in the child welfare system and have negative outcomes. One of the ways we could mitigate this is using cash assistance to address adversities in child well-being caused by economic hardship. Research points to an association between material hardship – the inability to provide needs such as food, medical care, housing – and increased risk for involvement in the child welfare system.[55] Parents who are unable to support their children due to poverty may be targeted. By diverting funds towards cash assistance and reducing risk for what is defined as neglect and abuse, there will be less need to spend money on the child welfare system.

It’s particularly concerning that the state has increased TANF dollars spent on child welfare services, shifting funds away from cash assistance. As seen in Chart 6, the state spent more than twice as much on child welfare services in 2021 and 2022 than it did in 2019. While fiscal year 2023 does not have updated data and fiscal 2024 is underway, it’s important to point out that in previous years, actual spending in this category has surpassed what was initially allowed.

-

Increase the Temporary Cash Assistance earned income disregard

In order to be eligible for TANF, states must count family earnings – with differences on a state-by state basis – and determine whether the earnings exceed the allowable amount to receive cash assistance. States often have income eligibility thresholds that are low and make it hard for families to qualify for and maintain TANF. The earned income disregard is the amount of income received from unsubsidized employment, including self-employment, which may be deducted or “disregarded” when determining eligibility and benefits. States vary in the way they calculate and impose the earned income disregard. Some states have earned income disregards for initial income eligibility purposes and then additional disregards for calculation of benefits, and others impose an initial income test where the calculation of the test and disregards allowed for the test are the same as those used to calculate the benefit. Moreover, earned income disregards may change depending on how long a family has received assistance, among other differences in states. In Maryland, already-employed adults new to TCA may have 20% of their gross earned income disregarded (50% if self-employed), while adults who are employed while receiving assistance may have 40% of their gross earned income disregarded (50% if self-employed). There are other states that have a higher earned income disregard than Maryland, including:[56]

- Maine

- When determining eligibility for cash assistance, Maine disregards $108 and 50% of the remaining earnings for all months. They also disregard 100% of all earned income for the first three months of employment, and 75% of all earned income for the 4th to 6th months of employment.

- Vermont

- In 2022, Vermont passed a bill that increased the earned income disregard from $250 plus 25% of remaining unsubsidized earnings to $350 plus 25% of remaining unsubsidized or subsidized earnings.

- Massachusetts

- The state disregards $200 for work expenses at initial application when determining eligibility (unless you received TANF within the four months before the application), and then disregards 100% of earned income in the first six months of earnings, then $200 and 50% of the remainder.

- New Jersey

- The state disregards 100% of earned income in the first month of earnings, 75% in the following six months, and 50% thereafter.

- Pennsylvania

- The state disregards $90 at the initial application (if a person is new to TANF or has not received TANF in one of the four calendar months before the application), but then disregards 50% of earnings and $200 of the remainder in all months when determining benefit amounts.

Maryland can also increase its earned income disregard to 75%, so that families can earn more without having their TANF benefits reduced or taken away as they strive for self-sufficiency. A higher earned income disregard would be specially important to families as they settle into their new employment, so that families can slowly and successfully transition away from the need for cash assistance.

-

Eliminate the classification of housing assistance as unearned income when determining cash assistance benefit amounts

Any assistance designed to provide a roof over someone’s head should not result in a reduction of cash benefits. Maryland’s TCA program currently counts the first $60 in housing assistance as unearned income which is then counted when calculating benefit amounts for families. Rather than offsetting benefits of one program due to gaining benefits in another, all types of assistance should build on each other to maximize positive outcomes for children and families living in poverty. This practice only harms families as their already-low cash benefit amount is not sufficient to stay afloat. In fact, ample research suggests that increase in, or greater access to, cash assistance is associated with better housing outcomes including a reduction in homelessness.46 Moreover, increasing cash assistance and thus having more money available for housing is more likely to benefit Black and Latinx children who face higher levels of housing insecurity.

-

Provide families with additional cash support to afford the high cost of housing

Maryland has one of the highest housing costs in the nation, and families that receive TCA cannot afford unsubsidized rent in the state. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, seven counties in Maryland, including counties with a higher concentration of families in TCA such as Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and Anne Arundel County, have a fair market rent for an unsubsidized two-bedroom apartment of $1,548, or more than two times the maximum TCA benefit for a household of three people.[57] An additional five counties have a fair market rent of $1,838 for a two-bedroom, including Montgomery and Prince George’s counties where there are also a large share of families receiving TCA. The lack of affordable or subsidized housing only places an additional burden for families with the lowest incomes who are eligible for housing assistance programs but are often left out or are placed in long waiting lists. It is clear that families on TCA need supplemental payments that can help cover housing costs. Helping families afford housing expenses will not only help address housing insecurity, it can also help begin the process of course-correcting racial inequities in housing resulting from a long history of discrimination against Black families and other families of color.

While raising the TCA benefit amount should be priority, Maryland can follow other states that allow families receiving TANF to receive housing allowances in addition to their regular cash benefits. In the 2023 legislative session, House Bill 562 aimed to provide a housing allowance for families receiving TCA, starting at $350 per month for one person and an additional $100 per month for each additional household member. However, the bill did not pass.

Conclusion

Many of the federal welfare reform programs, including TANF, were founded on racist and sexist beliefs that continue to influence modern-day TANF policies that target and surveil women of color, especially Black and unmarried women.11 These policies have created a system that undermines TANF’s reach and possibility for success. Shaping TANF programming to be more equitable, and ensuring that the distribution of TANF funds prioritizes families most in need, can move recipients towards an improved standard of living. This will require both a recognition of current shortcomings and a willingness for structural transformation. Maryland has made improvements to its TANF program in recent years and should continue building on that progress by centering the experiences of directly-impacted people as the state makes additional changes.

While the state can reshape its TANF program, it is also necessary to continue to advocate for changes at the federal level. Current TANF funding structures—such as the fixed federal block grant and states’ flexibility in how their respective programs are administered, erode TANF’s capacity to keep up with evolving needs and can leave families with the lowest incomes out of a social safety net. Federal and state governments must also work in tandem to deliver quality services.

Above all, we must underscore the importance of direct cash assistance in lifting families out of poverty. The reality is that money is indispensable to live and increases in prices for gas, groceries, or diapers do not bear in mind people going through a rough patch. We can do more for families by ensuring that cash assistance makes up the majority of combined TANF spending in the state.

Appendix

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview

*Numbers may not add up due to rounding

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal Budget Overview Documents 2018-2024

*Do not reflect actual amounts, just appropriations or allowances for those years

Source: Maryland Department of Human Services Fiscal Budget Overview Documents 2018-2024

*Do not reflect actual amounts, just appropriations or allowances for those years

Notes

[1] Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2023). 2023 KIDS COUNT® Data Book: State trends in child well-being. https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/aecf-2023kidscountdatabook-2023.pdf

[2] States’ fiscal years do not always align with that of the federal government. Maryland’s fiscal year 2022 ran between July 1, 2021 and June 30, 2022. The federal fiscal year 2022 ran between October 1, 2021 and September 30, 2022.

[3] Smith, H., & Passarella, L.L. (2023). Life on welfare, 2022: Temporary cash assistance in the pandemic recovery. University of Maryland School of Social Work. https://familywelfare.umaryland.edu/reportsearch/content/reports/welfare/Life-on-Welfare,-2022.pdf

[4] Some cases may not have a parent/adult receiving assistance, though some families have parents who are part of the unit but are not receiving assistance due to sanctions, among other reasons.

[5] Office of Family Assistance. (2023). Characteristics and financial circumstances of TANF recipients, fiscal year 2021 [Data set]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/data/characteristics-and-financial-circumstances-tanf-recipients-fiscal-year-2021

[6] Waxman, S., Sherman A., & Cox, K. (2021). Income support associated with improved health outcomes for children, many studies show. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/income-support-associated-with-improved-health-outcomes-for-children-many

[7] Vilorio, D. (2016). Education matters. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2016/data-on-display/education-matters.htm#:~:text=Even%20if%20your%20career%20path,decreases%20as%20educational%20attainment%20rises

[8] This data do not include adults working outside of the state which may underestimate actual percentages.

[9] Economic Security Project. (2020, June 16). A killer stereotype. https://economicsecurityproject.org/resource/a-killer-stereotype/

[10] Floyd, I., Pavetti, L., Meyer, L., Safawi, A., Schott, L., Bellew, E., & Magnus, A. (2021). TANF policies reflect racist legacy of cash assistance. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance

[11] Haider, A., Goran A., Brumfield, C., & Tatum, L. (2022). Re-envisioning TANF: Toward an anti-racist program that meaningfully serves families. Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/re-envisioning-tanf/

[12]Although Maryland ran a TANF deficit from fiscal years 2011 through 2016, the state generated a positive balance in the following years allowing FY 2021 to open with close to $20 million. It was anticipated that funds would be depleted within that year due to anticipated higher TCA caseloads during the COVID-19 pandemic. In FY 2021, Maryland received a combined $255.5 million from its TANF base grant and contingency TANF funds. DHS appropriated $239.7 million in TANF expenditures, with an ending balance of $35.8 million.

[13] Contingency funds were meant to account for economic downturns. The federal fund is available to states that meet certain conditions: 1) they have an unemployment rate of at least 6.5%, that is 10% higher than in a three-month period compared to the same three-month period in either of the two prior years, or 2) their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) caseload over the most recent three-month period is at least 10% higher than the caseload in the corresponding period in fiscal 1994 or 1995. Maryland meets the latter.

[14] “Combined TANF funds” include the federal block grant and funds appropriated for TANF-allowable services from the state’s own money such as revenue from its general fund.

[15] Office of Policy Analysis. (2022). Department of Human Services fiscal 2023 budget overview. Department of Legislative Services. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/Pubs/BudgetFiscal/2023fy-budget-docs-operating-N00-DHS-Overview.pdf

[16] Family Investment Program (FIP) is the state’s program for serving families in TANF. It encompasses the provision of Temporary Cash Assistance (TCA) in efforts to divert potential applicants through employment, move adults to work, and provide retention services to enhance skills and prevent recidivism. The goal of the FIP is to assist TCA applicants/recipients in becoming self-sufficient.

[17] There appears to be a discrepancy between the state’s spending data used in this report and the data that the state reports to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This analysis is based on Maryland’s Department of Human Services Fiscal 2023 Budget Overview’s state budget data for FY 2021. These state data do not include a break-out line for child care but do include a line for pre-K spending through the Maryland State Department of Education. It appears that the funds reported as state spending for pre-K do not include any child care. HHS requires separate reporting categories for pre-K spending and for child care spending. In federal fiscal 2021, the state reported to HHS $5.4 million in childcare spending (wholly separate from pre-K spending), representing 0.9% percent of total TANF and MOE spending based on HHS calculations.

[18] Office of Family Assistance. (2022). TANF financial data – FY 2021 [Data set]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/data/tanf-financial-data-fy-2021

[19] Office of Community Services Division of Social Services. (2021). Social services block grant: Fiscal year 2020 annual report. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocs/RPT_SSBG_Annual%20Report_FY2020.pdf

[20] Maryland’s Office of Adult Services focuses on the needs of elderly, disabled, and vulnerable adults.

[21] Office of Policy Analysis. (2023). Department of Human Services fiscal 2024 budget overview. Department of Legislative Services. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/Pubs/BudgetFiscal/2024fy-budget-docs-operating-N00-DHS-Overview.pdf

[22] Partly due to additional supplemental funds such as the TANF Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund also made available through ARPA. This fund was meant to cover administrative costs and non-recurrent short term benefits.

[23] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2023). Maryland TANF spending. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/tanf_spending_md.pdf

[24] Siegel R., & Bhattarai, A. (2023, July 12). Inflation drops to lowest levels since March 2021 as economy cools. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/07/12/june-cpi-inflation-report/

[25] Umunna, N. (2023, April 18). Family Prosperity Act extends, strengthens working family tax credits for more than 400,000 Marylanders. Maryland Center on Economic Policy. https://www.mdeconomy.org/family-prosperity-act-extends-strengthens-working-family-tax-credits-for-more-than-400000-marylanders/

[26] Banerjee, A., & Zipperer B. (2022, September 13). Pandemic safety net programs kept millions out of poverty in 2021, new Census data show. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/pandemic-safety-net-programs-kept-millions-out-of-poverty-in-2021-new-census-data-show/

[27]MDCEP calculation from the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, comparing June 1994 to June 2023. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[28] Greenberg, M. (2002). The TANF maintenance of effort requirement. Center for Law and Social Policy.https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/archive/0035.pdf

[29] Please see references list for a more detailed explanation of the limitations and requirements for services/programs under a MOE requirement.

[30] Office of Family Assistance. (2004). TANF-AFC-PA-2004-01 (Clarification that third party cash or in-kind may count toward a state’s or territory’s TANF maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/policy-guidance/tanf-acf-pa-2004-01-clarification-third-party-cash-or-kind-may-count-toward

[31] Falk, G. (2023). The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant: A primer on TANF financing and federal requirements. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL32748

[32] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2022). TANF cash assistance should reach many more families in Maryland to lessen hardship. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/tanf_trends_md.pdf

[33] Between fiscal years 2016 to 2020, Maryland spent 7% or less in total MOE state dollars for cash assistance. However, in 2021, Maryland spent around 17% of its MOE dollars in cash, disrupting the pattern.

[34] The approved FY 2024 budget included a supplement of $45 per month per person in cash assistance that began during the pandemic, thus an additional $135, for example, is added to $727 for a family of three for a total of $862 per month. This covers 42% of the federal poverty level for a family of three.

[35] MDCEP calculation based on the federal poverty level for a family of 3 for 2023.

[36] FMRs are housing market-wide estimates developed by HUD to determine payments for various housing assistance programs, which are calculated as the 40th percentile of gross rents for regular (non-subsidized, low-quality, or new apartments) and standard-quality units in certain areas.

[37] National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2023). Out of reach: Maryland. https://nlihc.org/oor/state/md

[38] Economic Policy Institute. (2022). Family budget calculator. https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/

[39] MDCEP calculation from the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, comparing June 2020 to June 2023. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[40] Section 5-316 of the Human Services Articles, found at https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Laws/StatuteText?article=ghu§ion=5-316&enactments=false

[41] The State Minimum Living Level was created from the 1979 Governor’s Commission on Welfare Grants, and requires DHS to use the annually updated findings as a basis for evaluating budgetary requirements for public assistance programs. It is based on a three person household and calculated based on needs such as food, rent, utilities, clothing and cleaning, personal care, transportation, medical care, household furnishings, and other consumption. It is updated annually only to account for inflation, but does not account for regional differences in cost of living.

[42] Thompson, G.A., Azevedo-McCaffrey, D., & Carr, D. (2023). Increases in TANF cash benefit levels are critical to help families meet rising costs. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/increases-in-tanf-cash-benefit-levels-are-critical-to-help-families-meet-0

[43] Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity. (2023). City launches guaranteed income pilot-study for E-TANF beneficiaries in Philadelphia. City of Philadelphia. https://www.phila.gov/2023-08-11-city-launches-guaranteed-income-pilot-study-for-e-tanf-beneficiaries-in-philadelphia/

[44]Oregon Department of Human Services. (2022). Nonrecurring short-term payments for TANF. https://www.dhs.state.or.us/policy/selfsufficiency/publications/ss-pt-22-017.pdf

[45] Council of the District of Columbia. (2022). Engrossed version of the FY2023 BSA. https://lims.dccouncil.gov/downloads/LIMS/49079/Meeting2/Engrossment/B24-0714-Engrossment1.pdf

[46] Zane, A., Reyes, C., & Pavetti, L. (2022). TANF can be a critical tool to address family housing instability and homelessness. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-can-be-a-critical-tool-to-address-family-housing-instability-and

[47] Smith, H., Hall, L.A., & Passarella, L.L. (2022). Life after welfare: 2022 annual update. University of Maryland School of Social Work. https://www.ssw.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/fwrtg/welfare-research/life-after-welfare/Life-after-Welfare,-2022.pdf?&

[48] Maryland Child Resource Network. (2022). Child care demographics 2022. Maryland Family Network. https://www.marylandfamilynetwork.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/MFN_Demographics2022%20Final%20%281%29.pdf

[49] Office of Policy Analysis. (2023). Analysis of the FY 2024 Maryland executive budget, 2023- Early Childhood Development. Department of Legislative Services. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/Pubs/BudgetFiscal/2024fy-budget-docs-operating-R00A99-MSDE-Early-Childhood-Development.pdf

[50] See page 15, Office of Policy Analysis. (2023). Analysis of the FY 2024 Maryland executive budget, 2023 – Family Investment Administration. Department of Legislative Services. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2024fy-budget-docs-operating-N00I00-DHS-Family-Investment.pdf

[51] National Conference of State Legislatures. (2023). Child support pass-through and disregard policies for public assistance recipients. https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/child-support-pass-through-and-disregard-policies-for-public-assistance-recipients

[52] Smith, H., & Hall, L.A. (2021). Maryland’s child support pass-through policy: Exploring impacts on TCA families. University of Maryland School of Social Work. https://familywelfare.umaryland.edu/reportsearch/content/reports/welfare/Pass-Through-Impacts-on-TCA-Families.pdf

[53] H.464 (Act 133). (2022). Vermont General Assembly. https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2022/Docs/ACTS/ACT133/ACT133%20Act%20Summary.pdf

[54] See Public Law 104-193, https://www.congress.gov/104/plaws/publ193/PLAW-104publ193.pdf

[55] Shrivastava, A., & Patel, U. (2023) Research reinforces: Providing cash to families in poverty reduces risk of family involvement in child welfare. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/research-reinforces-providing-cash-to-families-in-poverty-reduces-risk-of#_ftn1

[56] Welfare Rules Database. (2023). Table II.A.1. Earned income disregards for benefit computation, July 2021 [Data Set]. Urban Institute. https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/query/query.cfm

[57] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). FY 2023 Fair Market Rent documentation system: The FY 2023 Maryland FMR summary. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmrs/FY2023_code/2023state_summary.odn