Maryland Must Commit to Providing Safety and Stability for All Children in Foster Care

When children are facing a crisis, it is critical that Maryland’s foster care programs provide them with stable, safe and supervised care. Recent media reports of foster youth being housed in unlicensed facilities suggest that the state is not living up to this basic standard. The report indicates that foster children were placed in hotels, a commercial office building in downtown Baltimore and in some cases were left in emergency departments and other sections of hospitals even though they had no medical reason for being there.

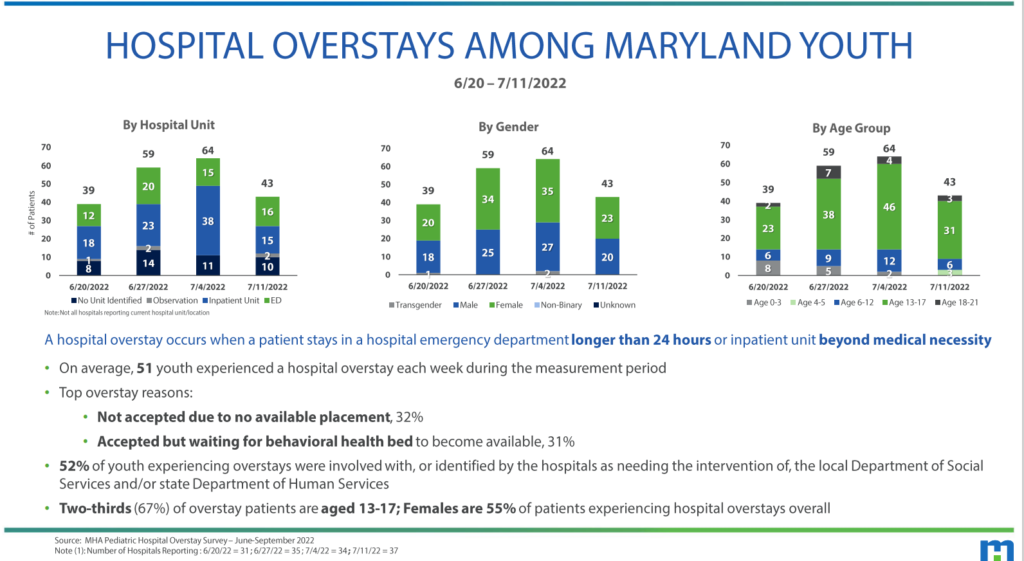

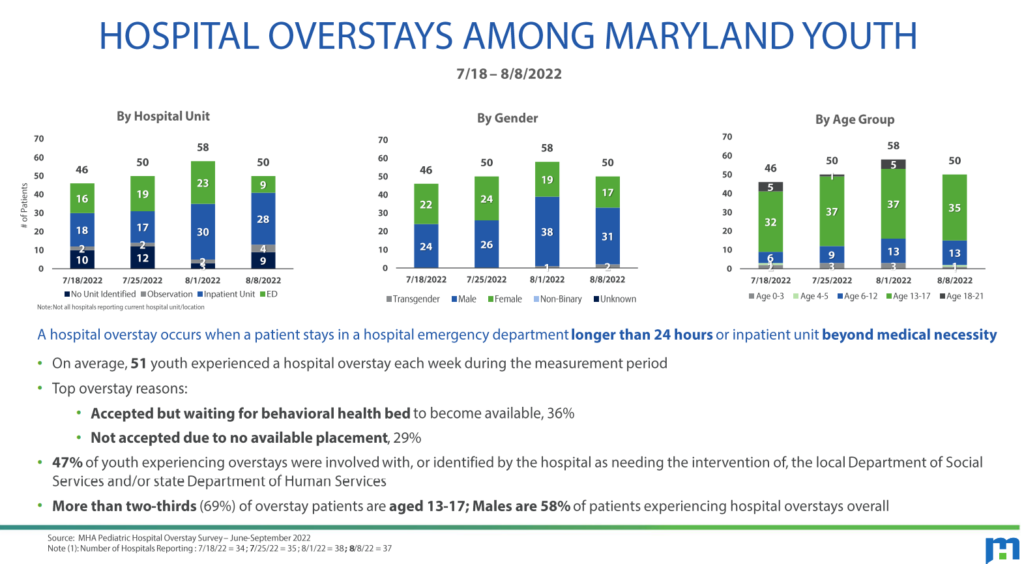

So far, we know that in the first six months of this year, 11 children have spent at least one night at the Baltimore City Department of Social Services office building while 56 have been placed there for a total of 200 hours. According to the Baltimore Banner analysis, each year 80-100 children in state custody stay in hospitals longer than medically needed, mainly due to lack of licensed placement options.

Addressing these issues will requires additional funding for foster youth services, additional supports for foster families, and creating residential facilities that can provide safety, stability, and needed services for children and youth needing more intensive behavioral health care.

For years, advocates and stakeholders in the foster care system have stated that children are better served in family homes rather than in facilities. This led to the downsizing of institutions and group home placements. However, in making this transition, state policymakers failed to invest in community-based programs and out-of-home placements that provide specialized care for foster children with greater behavioral health needs. Between 2007 and 2015 more than 350 congregate care beds, most of which were licensed by the Maryland Department of Health, were closed. No plan was made to replace any of these beds, in part because group homes were viewed less favorably.

As of 2022, there are only four residential treatment centers and four therapeutic group homes left in the state. About 1 in 4 children who are placed in settings other than a family home are older children with high intensity and complex needs. These two factors lead to hospital overstays, meaning children are kept in inpatient psychiatric facilities longer than they need to be or are stuck in emergency rooms simply because there are no placements available. A 2021 report released by the Maryland Hospital Association found that the primary reasons for delays in discharging foster youth were aggressive behaviors, diagnosis of developmental disability and/or autism with psychiatric features, sexually reactive behavior, and age (too young/too old).

Often when all other placement options are exhausted, youth with high intensity needs are placed in hotels. None of this is new, but COVID-related staff shortages have increased the frequency of hospital overstays and placements in hotels. Some of the youth placed in hotels are left to take care of themselves. They lack access to nutritious food, are often absent from school or drop out all together because of the distance between the hotel and their school. They are also denied the clinical care of licensed social workers who cannot work in the unlicensed facilities the children are placed in.

The state is spending roughly $10 million per year for additional staff to supervise youth who are in placements that doesn’t meet their needs. These staff are typically untrained and hired simply for the purpose of additional supervision. These placements are considered a last resort to hold children when foster families, group homes or other residential facilities aren’t available.

The current situation indicates that there is a systemic failure that existed way before the pandemic started. To put it simply, the choice shouldn’t be between no placement at all or illegal placements. The Department of Human Resources has found its responsibilities expand from not just caring for maltreated children but also for those with therapeutic needs, all while having little to no resources to meet those needs.

It is clear that state officials have failed to adequately provide the services and facilities needed to ensure that children in foster care are placed in the proper environment and that their mental health needs are met. According to the National Association of Social Workers, Maryland Chapter the following steps can begin to address this issue:

- Provide adequate funding and resources that meets the needs of children in the foster care system including investing in treatment and therapeutic foster care.

- Require MDH to develop a 25-bed psychiatric respite with a policy that will ensure that youth staying there have a safe and therapeutic place while awaiting a longer-term placement

- Increase funding for lagging provider rates and complete the stalled rate

reform process. Given Child Welfare’s reliance is on a partnership with private placement providers, ensuring a business environment and rate setting process that attracts and supports quality providers who can meets the needs of children with complex needs is imperative.

- Expand residential treatment capacity

- Strengthen behavioral health prevention with wraparound and mobile crisis that includes hospital and placement diversion

- Recruit and train more foster care families to care for children with disabilities, gender non-conforming children, and young people who are English language learners. It is clear that we are lacking in foster care parents who can met these specific needs of foster kids.

- Offer Medicaid reimbursement for mobile crisis teams. These teams visit foster care families in prior to or during emergencies. Their absence denies foster families a source to reach out to in times of crisis.