Strengthening the Minimum Wage Would Benefit 40,000 Howard County Workers

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted Maryland communities’ deep reliance on the workers who keep families fed, care for aging adults, and maintain sanitary public spaces. Yet these same workers too often take home wages that cannot support a family, let alone compensate for the daily risks their jobs require. Strengthening the minimum wage in Howard County would make an important difference to the workers who keep local communities going, support a strong recovery, and benefit children for decades to come.

In 2019, the Maryland General Assembly laid the groundwork for a $15 minimum wage statewide by 2026 (with most workers reaching $15 by 2025). However, this law was the product of a series of compromises that delayed wage increases for most workers and left some out entirely. Strengthening the minimum wage in Howard County would reduce the harmful impacts of these compromises. Council Bill 82-2021 accomplishes this by:

- Accelerating the increases called for under state law so that most workers are guaranteed $15 per hour by 2023 and those at small employers reach $15 in 2024

- Increasing the minimum wage to $16 per hour in 2025 for most workers and in 2026 for those at small employers

- Adjusting the minimum wage for inflation in future years to ensure that it keeps up with the rising cost of living

The fact is, workers in Howard County cannot get by on low wages. Between housing, food, clothing, and other essentials, even a single adult in Howard County, working full time and not caring for children, would need to take home $22.28 per hour to afford a basic living standard, according to the Economic Policy Institute.[i] That cost only increases for workers supporting a family.

A stronger minimum wage would boost Howard County workers’ income by $43 million by 2026:[ii]

- Workers benefiting: 40,000 (25% of Howard County workers)

- Total wage increase: $43 million in 2026 (constant 2020 dollars)

- Average wage increase: $1,100 in 2026

- Cumulative wage increase, 2022–2024: $161 million

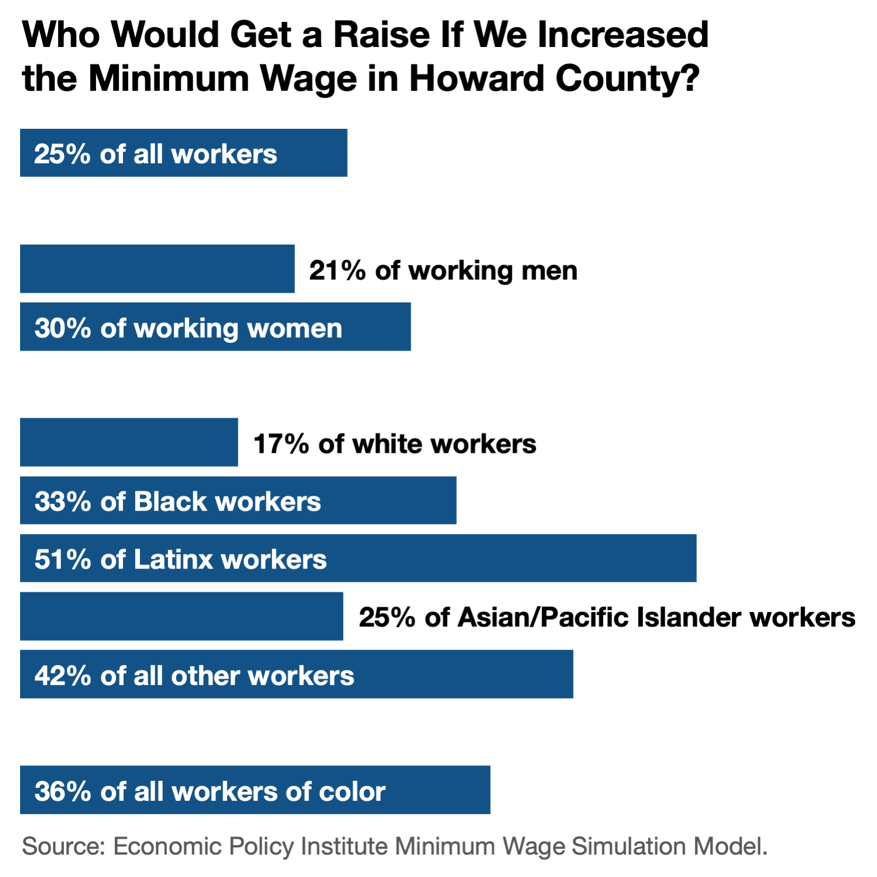

A stronger minimum wage would make Howard County’s economy more just and inclusive. Here’s who would benefit:

-

- 30% of working women

- 33% of Black workers

- 51% of Latinx workers

- 25% of Asian and Pacific Islander workers

- 75% of workers in low-income families

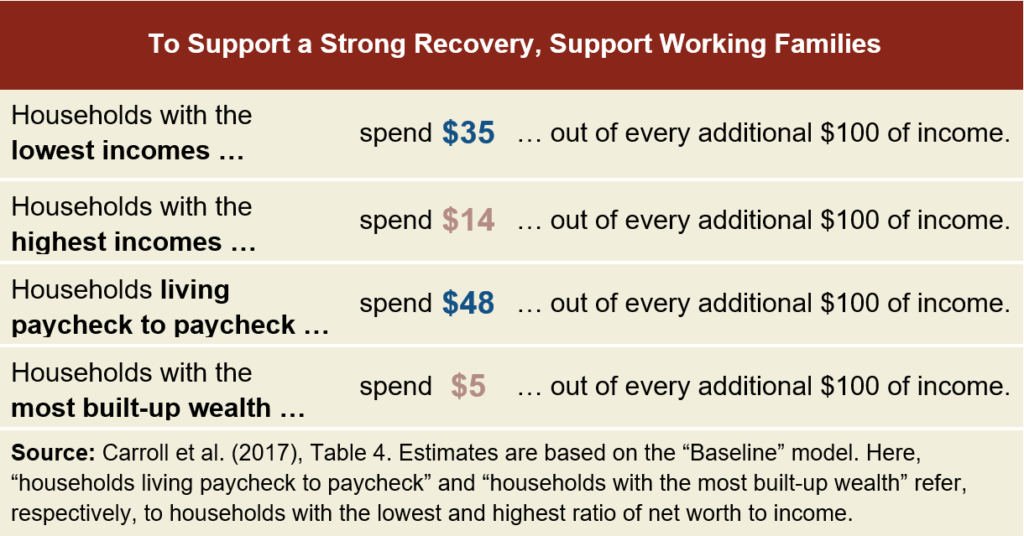

Finally, because families who live paycheck to paycheck quickly use new income to pay for necessities, strengthening the minimum wage would boost sales at Howard County businesses and strengthen the local economy.

By the Numbers

Strengthening the minimum wage in Howard County would increase incomes for 40,000 workers by an average of $1,100, totaling $43 million in increased wages in 2026.

A stronger minimum wage would benefit workers of every background, and would be especially meaningful for women and workers of color, who today are often held back by structural barriers built into our labor market.

| Howard County Minimum Wage Highlights

See appendix for full demographic analysis. |

|||

| Who Would Get a Raise? | How Many Workers? | How Much on Average? | How Much Altogether? |

| Overall | 40,000 | $1,070 | $43 million |

| Women | 21,700 | $1,040 | $22 million |

| Black Workers | 11,400 | ≥ $1,250 | ≥ $14 million |

| Latinx Workers | 7,700 | ≥ $1,070 | ≥ $8 million |

| Workers of Color Overall | 24,900 | $1,150 | $29 million |

| Age 20+ | 35,000 | $1,100 | $38 million |

| Parents | 8,700 | $1,010 | $9 million |

| Full-Time Workers | 23,000 | $1,260 | $29 million |

| College Graduates | 7,600 | ≥ $790 | ≥ $6 million |

| Family Income < $25,000 | 7,100 | $1,300 | $9 million |

| Source: Economic Policy Institute Minimum Wage Simulation Model; see Technical Methodology by Dave Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer. https://www.epi.org/publication/minimum-wage-simulation-model-technical-methodology/

Notes:

|

|||

Long-Lasting Benefits

A large body of research shows that when families earn enough to afford the basics, the benefits ripple out to nearly every part of their lives. A 2013 systematic review of academic literature linked higher family incomes to:[iii]

- Fewer families struggling to put food on the table

- Increased spending on children’s clothing, reading materials, and toys

- Fewer behavioral problems, less physical aggression, and less anxiety among children

- Improved academic and cognitive test results, and more years of schooling completed

Adequate wages are also linked to individuals’ and families’ physical health:

- An analysis of every birth record in the United States between 1989 and 2012 found that after states raised their minimum wages, babies in those states had a longer average gestational length and were less likely to be born underweight.[iv]

- The same study found that people who became pregnant following a state minimum wage increase were more likely to obtain adequate prenatal care and less likely to smoke during pregnancy.

- Another analysis of birth records found a link between state minimum wages and birth weight as well as lower infant mortality.[v]

- In 2016, the American Public Health Association issued a policy statement officially calling for a higher minimum wage.[vi] The statement documented multiple links between income and health and noted that “current metrics for setting minimum wages inadequately capture the basic necessities for living in full health.”

A Stronger Minimum Wage Will Support a Robust Economic Recovery

As Maryland communities rebound from the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic, maintaining consumer demand is key to bringing about a robust recovery. A stronger minimum wage will make this job easier. More than anyone else, families living paycheck to paycheck quickly cycle every dollar of income back into the local economy by buying essentials.[vii] A higher minimum wage means higher incomes for precisely the families who will spend that money fastest. This, in turn, means stronger sales at local businesses, which allows them to hire more workers.

A higher wage standard may also draw more people into the labor market and make it easier for businesses to hire. While COVID-19 concerns remain the most important factor influencing workers’ job search decisions in the near term, a higher wage standard would make Howard County a more attractive place to work in the long run, potentially leading to more application for positions at local businesses.

Finally, the most rigorous economic research undermines catastrophic predictions about the effect of a higher minimum wage on the economy:

- A study published in 2019 examined 138 state minimum wage changes between 1979 and 2016. The study found no evidence of any reduction in the total number of jobs for low-wage workers and no evidence of reductions affecting subsets of the workforce such as workers without a college degree, workers of color, and young workers.[viii]

- A 2016 meta-analysis of 37 studies on the minimum wage published since 2000 found minimal employment effects, particularly for the vast majority of workers affected by the minimum wage who are at least 20 years old.[ix]

- A study published in 2016 assessed a range of statistical methods used in the literature to estimate employment effects of the minimum wage.[x] Analyses using a diverse set of credible approaches find negligible effects on employment. The authors identified analytical problems with methods that found negative effects, calling into question the suitability of these methods for distinguishing the effect of the minimum wage from preexisting labor market trends.

Appendix: View additional details

References

[i] Economic Policy Institute 2018 Family Budget Calculator, http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/

[ii] Source for all impact estimates is the Economic Policy Institute Minimum Wage Simulation Model; see Technical Methodology by Dave Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer. https://www.epi.org/publication/minimum-wage-simulation-model-technical-methodology/

[iii] Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart, “Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes? A Systematic Review,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, October 2013, https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/money-children-outcomes-full.pdf

The systematic review methodology involves defining in advance how researchers will identify relevant studies, as well as quality control measures to ensure that only studies with credible methodologies are included. This methodology protects against researchers cherrypicking studies that support their viewpoint.

[iv] George Wehby, Dhaval Dave, and Robert Kaestner, “Effects of the Minimum Wage on Infant Health,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39(2), 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22174

[v] Cooper and Stewart 2013.

[vi] “Improving Health by Increasing the Minimum Wage,” American Public Health Association, November 2016, https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2017/01/18/improving-health-byincreasing-minimum-wage

[vii] Christopher Carroll, Jiri Slacalek, Kiichi Tokuoka, and Matthew White, “The Distribution of Wealth and the Marginal Propensity to Consume,” Quantitative Economics 8(3), 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3982/QE694

[viii] Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer, “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3), 2019, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/134/3/1405/5484905

[ix] Paul Wolfson and Dale Belman, “15 Years of Research on US Employment and the Minimum Wage,” Labour 33(4), 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/labr.12162

[x] Sylvia Allegretto, Arindrajit Dube, Michael Reich, and Ben Zipperer, “Credible Research Designs for Minimum Wage Studies: A Response to Neumark, Salas, and Wascher,” ILR Review 70(3), 2017, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0019793917692788