Budgeting for Opportunity: Our Shared Investments Can Build Safe, Just, Thriving Communities

With activists across the state calling for greater investment in communities, rather than punishment, and a viral pandemic putting the lives of incarcerated people at greater risk, it is more critical than ever that Maryland undertake serious review of its spending on incarceration and other parts of the criminal legal system.

Changing our approach to the state’s criminal legal system would open new opportunities to build stronger communities. Policy choices made over the last half century have put far too many Marylanders of every racial and ethnic background behind bars and disrupted communities in every part of our state. At the same time, Maryland’s long and continuing history of discriminatory policy choices—in our criminal legal system as well as in areas such as housing, education, and transportation—have distributed these harms unevenly. As a result, Marylanders of color—in particular Black and Indigenous Marylanders—and people living with psychiatric conditions, substance use disorders, or disabilities are more likely than other residents of our state to be incarcerated.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it even more urgent to reshape Maryland’s criminal legal system. The state confines thousands of our state’s residents in conditions that are dehumanizing in the best of times, and now pose a significant health hazard.

There is much state policymakers can do to reverse this state of affairs. A robust body of research developed over the last several decades has shed light on policy strategies that can foster safe communities while restoring freedom to thousands of Marylanders who are now incarcerated.

No single reform can accomplish this. However, two complementary strategies can move us a long way in the right direction and redirect state funding away from the criminal legal system: investing in the foundations of thriving communities such as quality health care and welcoming public spaces, and creating good jobs that can support a family.

Key Findings

Despite recent progress, Maryland still incarcerates its population at a rate that dwarfs historical experience, significantly exceeds incarceration rates in some comparable states, and is massively out of step with global norms.

- Maryland’s reliance on incarceration is heavily lopsided. Black Marylanders are 4.5 times more likely to be incarcerated in state prison than those Marylanders belonging to other racial and ethnic groups. American Indian/Alaska Native Marylanders are more than twice as likely as other Marylanders to be in state prison.

- Mass incarceration is incompatible with maintaining good public health amid a deadly pandemic. At least 13 people incarcerated in Maryland and two staff have died of COVID-19 so far, with nearly 1,800 others contracting the virus. The only way to meaningfully protect incarcerated Marylanders from premature death is to rapidly reduce prison and jail populations and provide the supports necessary for returning citizens to transition safely back into the community.

- Strong evidence links a healthy economy—one in which good, family-supporting jobs are available and realistically accessible—to safe communities. On the other hand, there is scant evidence that the draconian sentencing policies that have filled Maryland’s prisons and jails to capacity meaningfully improve public safety.

Our shared investments in the foundations of thriving communities contribute meaningfully to public safety. Sufficiently funded schools increase graduation rates and raise adult earnings. Inviting public spaces foster vibrant, stable neighborhoods. Effective drug treatment can reduce relapses and save lives. Moreover, we can use our shared investments to create high-quality jobs and dismantle economic barriers.

Summary of Recommendations

The billions we spend on putting people in jails and prisons are billions that we could instead invest in things that improve communities and reduce crime, like addiction treatment, mental health care and good schools.

Recent experience suggests that incarcerating one additional person in a Maryland prison costs about $14,000, or about $1 million per 70 incarcerated people. However, the goal of ending mass incarceration must be to advance justice, not just to cut costs. Policymakers must reject “incarceration on the cheap,” which would only further harm incarcerated Marylanders and their families and communities. We must also guarantee that people transitioning back to the community have the support they need to keep a roof over their head and food on the table, to find and keep a good job, and to access needed health care.

- Major sentencing reform is the most important step to significantly decrease the number of people incarcerated in Maryland. Sentencing practices in the United States are out of step with international norms for minor and serious offenses alike. The best research shows that comprehensive sentencing reform is compatible with supporting safe communities.

- We must end policies like criminal legal system fines and fees and driver’s license revocation as punishments because they effectively criminalize poverty.

- We must replace criminalization of work in the underground economy that people engage in to survive with effective, non-punitive alternatives.

- We must strengthen Marylanders’ right to due process when they are accused of a crime. This entails steps such as finishing the job of bail reform, adequately funding and staffing the Office of the Public Defender, and requiring discovery before plea bargaining.

- While it is no substitute for restoring incarcerated Marylanders’ freedom, we can take steps to improve conditions in prisons and jails, such as

- eliminating onerous copays and other fees,

- ensuring access to evidence-based drug treatment,

- guaranteeing incarcerated workers a fair wage,

- and granting incarcerated workers the right to join together and collectively negotiate the terms of their work.

- We should strengthen incarcerated Marylanders’ role in determining their own future through parole reform. We can do this by repealing the governor’s power to deny parole at will, establishing a presumption in favor of granting parole unless specific criteria are met to justify continued incarceration, and eliminating reincarceration for technical violations.

- We also should reduce barriers to opportunity for formerly incarcerated Marylanders. We can do this through steps like removing counterproductive restrictions in economic security programs such as housing assistance, increasing access to evidence-based drug treatment, and ending unnecessary inquiry into applicants’ past involvement with the criminal legal system by employers and occupational licensing bodies.

- We should revamp performance monitoring in our criminal legal system to center the wellbeing of incarcerated Marylanders and include equity measures.

Maryland’s criminal legal system is vast and complex, as are the injustices it breeds. This report focuses on fiscally significant state policy choices relating to incarceration. The path toward justice will require federal, state, and local policy changes far beyond the scope of this report, such as demilitarizing police departments and strengthening worker protections, along with many others.

Racism Is Deeply Embedded in our Criminal Legal System

In Maryland and nationwide, coercion, confinement, and punishment have played central roles in maintaining systems of racial domination since the colonial era. They were defining features of slavery. Maintaining racial hierarchy was also an important motivation in the early development of Maryland’s criminal legal system. Along with Virginia, Maryland pioneered the criminalization of interracial marriage in the late 17th century.[i]

Two centuries later, the role of the criminal legal system in maintaining white supremacy changed in the aftermath of the Civil War. Although the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolished slavery under most circumstances, it made an explicit exception for the use of involuntary servitude—slavery—as a criminal punishment. Especially after the end of Reconstruction, former slave states took advantage of this provision to once again subjugate many of their Black residents.[ii]

Both public policy and racist perceptions of Black criminality worked to entrench white supremacy outside the former Confederacy as Black communities in northern cities grew in the early twentieth century. False or sensationalized news stories of crime among Black residents fueled white mob violence to enforce neighborhood segregation. In many cases, police did little to stop this violence and prosecutors made little effort to prosecute its perpetrators. Efforts to rid white neighborhoods of crime and “vice” often pushed these activities into segregated Black communities, cementing the false perception of Black residents as inherently criminal.[iii]

The last century has been marked by a cycle of white violence—in some cases perpetrated directly by police or prison agencies, in others with their tacit approval—followed by civil unrest and heavy-handed law enforcement tactics. Experts found evidence of pervasive law enforcement bias in investigations of racial unrest in Chicago (1919), in New York (1935 and 1943), in Los Angeles (1965), and nationwide following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968.[iv] Similar dynamics have played out in recent years after police officers killed Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others.

While much has remained constant, our criminal legal system has also changed in important ways during the last 50 years. Beginning in the late 1960s and continuing through the mid-1990s, policymakers at the federal level and in all 50 states chose to enact increasingly punitive policies—especially sentencing policies—that caused a dramatic rise in the number of incarcerated Americans. Maryland played a special role in this transformation. The disdainful address Gov. Spiro Agnew delivered to Black civic leaders in Baltimore in the aftermath of the King assassination would help propel him to the vice presidency while setting the tone for decades of “tough on crime” rhetoric:

“To a degree unparalleled in U.S. history, politicians and public officials beginning in the 1960s regularly deployed criminal justice legislation and policies for expressive political purposes as they made ‘street crime’—real or imagined—a major national, state, and local issue.”[v]

Racialized Mass Incarceration by the Numbers

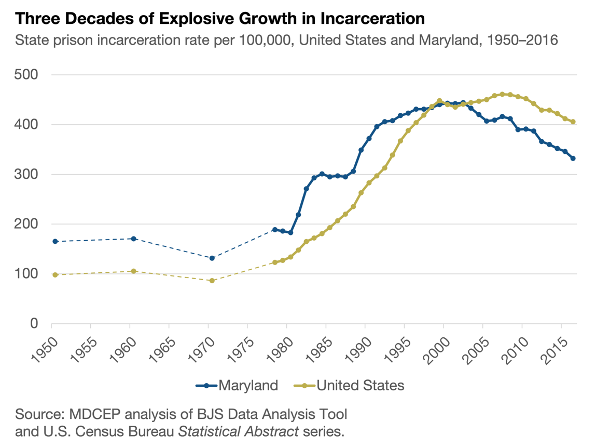

The policy changes drove a stratospheric rise in the nationwide incarcerated population.[vi] The number of Americans in state prisons increased from 176,000 in 1970 to 1.25 million in 2000—a sevenfold increase. The United States population increased by only 38 percent during that period.

Maryland followed a similar, though less extreme, path. The number of Marylanders incarcerated in state prisons grew by more than 350 percent from 1970 to 2000 (from 5,200 to 23,500), while the state’s population grew by only 35 percent (from 3.9 million to 5.3 million).

By 1982, Maryland’s incarceration rate had doubled since 1970. By 1991, it had tripled. Maryland’s incarceration rate topped out in 2002 at 3.4 times its rate in 1970. It subsequently fell by about 23 percent from 2002 to 2018, but Marylanders remained more than twice as likely to be confined in state prison as in 1970.

Mass incarceration extends beyond prisons. As of 2018, there were:[vii]

- 18,100 Marylanders in state prisons (299 per 100,000 population)

- 11,100 Marylanders in local jails (185 per 100,000), about two-thirds of whom had not yet stood trial

- 400 children confined in juvenile residential facilities[viii] (37 per 100,000)

- 81,200 Marylanders in the community on probation or parole (673 per 100,000)

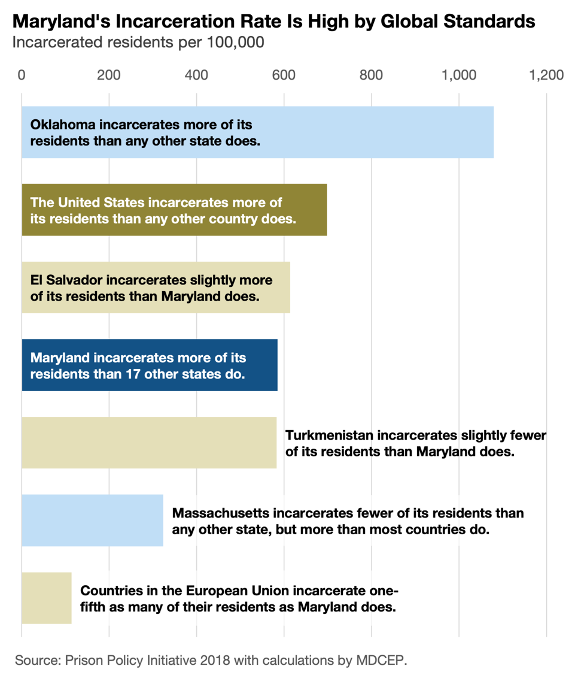

Maryland’s total incarceration rate is in the middle of the pack among the states:[ix]

- As of 2017, Maryland residents were 16 percent less likely to be behind bars than United States residents overall, but more likely than residents of 17 other states.

- Oklahoma, which incarcerates a larger share of its residents than any other state, has a total incarceration rate slightly less than double Maryland’s.

- Massachusetts, which incarcerates a smaller share of its residents than any other state, has a total incarceration rate slightly more than half of Maryland’s.

In a global context, Maryland’s incarceration rate is extreme:[x]

- Only two countries—the United States overall and El Salvador—lock up larger shares of their populations than Maryland.

- Turkmenistan incarcerates a slightly smaller share of its residents than Maryland does. Incarceration rates in Turkey and Iran are slightly below half of Maryland’s.

- Marylanders are about four times more likely to be incarcerated than residents of the European Union.

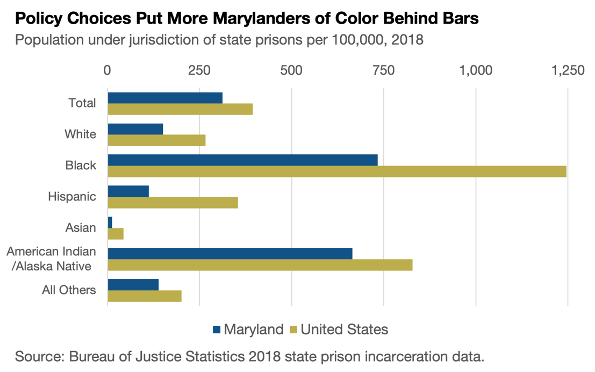

Our state’s reliance on incarceration has put too many Marylanders of every racial and ethnic background behind bars and disrupted communities in every part of our state. At the same time, these harms fall far more heavily on some than on others. For example, seven out of 10 Marylanders incarcerated in state prisons are Black, compared to three out of 10 Marylanders overall.[xi] Marylanders who identify themselves as American Indian/Alaska native constitute 0.24 percent of our state’s total population, but 0.52 percent of Marylanders in state prison.

Table 1 summarizes the impact of mass incarceration in Maryland and nationwide by racial and ethnic group.

|

Table 1. Racialized Impact of Mass Incarceration in Maryland and Nationwide |

||||||||

| Number Incarcerated in State Prisons | State Prison Incarceration rate

(Per 100,000 population) |

% of State Prison Population | Disproportionality Factor* | |||||

| Maryland | United States | Maryland | United States | Maryland | United States | Maryland | United States | |

| Total | 18,900 | 1.29 million | 312 | 394 | ||||

| White | 4,600 | 526,000 | 150 | 267 | 24% | 41% | –69% | –55% |

| Black | 13,200 | 505,000 | 734 | 1,246 | 70% | 39% | +451% | +356% |

| Latinx | 700 | 211,000 | 112 | 354 | 4% | 16% | –67% | –12% |

| Asian | 50 | 8,000 | 12 | 44 | < 0.5% | 1% | –96% | –89% |

| American Indian/ Alaska Native |

100 | 20,000 | 664 | 828 | 1% | 2% | +113% | +112% |

| All others | 200 | 15,000 | 139 | 201 | 1% | 1% | –56% | –50% |

| Source: MDCEP analysis of U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Prisoners in 2018 data and U.S. Census bureau Population Estimates data.

* The disproportionality factor reports how much more or less likely members of a specific group are to be incarcerated in state prison than people who are not members of the group. For example, Latinx Marylanders are 67 percent less likely to be in state prison than Marylanders who are not Latinx. |

||||||||

In historical context, even after nearly two decades of declining incarceration rates, higher shares of Black and Indigenous Marylanders are incarcerated today than Marylanders belonging to other racial and ethnic groups everwere.

Confinement of children in juvenile residential facilities is at least as lopsided. As of 2017, Black adolescents were almost 7 times as likely to be held in a residential facility as their white peers, and Latinx adolescents were nearly 1.8 times as likely as their white peers to be confined.[xii]

As of 2018, 675 Marylanders who are not United States citizens were incarcerated in Maryland prisons.[xiii] They are less likely than citizens to be in state prisons, accounting for 3.6 percent of Maryland’s prison population, compared to 8.2 percent of the statewide total population. Heavy-handed federal immigration enforcement means that any interaction with the criminal legal system poses especially high risks for people who are not citizens.

One out of 23 Marylanders in state prison are women (4.4 percent), compared to one out of 13 nationwide (7.6 percent).

Although Maryland-specific data are generally not available, research shows that the United States disproportionately incarcerates people who face a range of barriers in multiple domains of life—in many cases, barriers created through policy choices or worsened by inaction:

- A survey conducted in 2011 and 2012 found that people who identify themselves as lesbian, gay, or bisexual are more likely to be incarcerated than their straight counterparts. The study found that about 9 percent of men in prison and 42 percent of women identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.[xiv]

- In a survey of transgender women conducted in 2008 and 2009, 19 percent of respondents stated that they had ever been incarcerated.[xv]

- A 2009 study found that about 15 percent of men and 31 percent of women in a sample of Maryland and New York jails had a serious psychiatric condition.[xvi]

- Research has found that up to two-thirds of incarcerated adults live with a substance use disorder.[xvii]

- Research by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found that people with disabilities on average receive sentences 15 months longer than others convicted of the same offense.[xviii]

While the number of people in prison or jail at any given time remains alarmingly high, a much larger number of people have been incarcerated at some point in their lives.

- The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that as of 2001 (the most recent time the agency conducted this research), about 2.7 percent of adults in the United States has spent time in prison, including 4.9 percent of men and 0.5 percent of women.[xix]

- The Bureau of Justice Statistics analysis found significant racial disparities, with 8.9 percent of Black Americans, 4.3 percent of Latinx Americans, and 16.6 percent of Black men reporting time in prison.

- A 2018 nationally representative survey found that 19 percent of all respondents had spent any time in prison or jail in their lives, and 4 percent had been incarcerated for one month or longer.[xx]

- The 2018 survey found that one in four men, one in three Black respondents, and about half of American Indian/Alaska Native respondents had been incarcerated at some point. Among respondents in these groups who had ever been incarcerated about a quarter had spent a month or more in prison or jail.

- Three out of every 10 respondents with annual household income less than $25,000 reported having ever been incarcerated, compared to only one in 10 respondents with household income of $100,000 or more.

- Nearly half of the respondents to the 2018 survey reported that an immediate family member had been incarcerated, and one in seven had a family member who had been incarcerated for at least a year.

The Role of Economic Roadblocks and Policy Choices

Because of the racism embedded in our policing and criminal legal systems, money that state and local governments spend on police and prisons is largely going to reinforce racial disparities, rather than making investments that could strengthen communities.

State policy choices have an important role in determining how many—and which—people will be incarcerated. Policymakers in Maryland and nationwide spent multiple decades moving us toward higher levels of incarceration, both directly through draconian sentencing policies and indirectly by cutting back on basics like housing, health care, and education. We have since begun to reverse course, but there is still a long way to go.

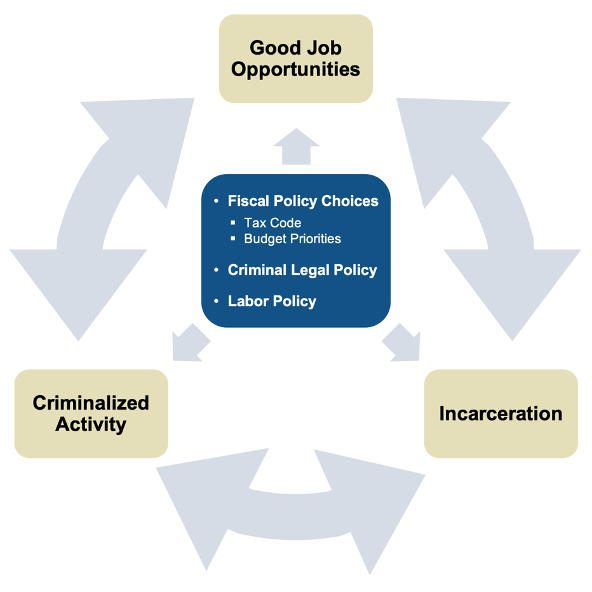

Harmful policy choices can increase the level of incarceration through two broad mechanisms.

Undermining thriving communities can increase criminalized activity

First, policies such as cutting back public investment in communities and chipping away at worker protections can leave some people with few legal options for making a living or otherwise increase the probability of engaging in criminalized activity. For example, weakening worker protections can lower wages and thereby leave people little choice but to break the law to make ends meet. Or, cutting back on mental and physical health care options can lead more people to self-medicate with criminalized substances. Because these harmful policy choices disproportionately target Black and Brown communities, their impacts can be similarly lopsided. For example, residents of the 50 Maryland ZIP codes with the highest unemployment rates are five times as likely as other Marylanders to be in prison.[xxi]

Nationwide, research shows that individuals who face the most dire economic circumstances are often the most likely to be incarcerated. Among people sentenced to one year or more in prison, only 20 percent report any income from a job in the year they enter prison, according to one study.[xxii] Slightly more than 40 percent report any income from a job in the year before incarceration, and less than one-third report taking home more than $15,000 per year before being incarcerated. While this analysis may have omitted unreported income generated through criminalized activities, research suggests that such income is rarely substantial and often serves as a form of moonlighting to supplement formal economy wages.[xxiii]

A growing body of high-quality research provides evidence of a causal link between economic insecurity and engaging in criminalized activity.[xxiv] Studies have linked criminalized activity to job loss, long-term unemployment, volatile or transient employment, lack of geographic access to jobs, and income inequality. Researchers generally find that low wages are the strongest predictor of engaging in criminalized activity.

This connection should come as little surprise. When people who work in the underground economy discuss their own motivations in interview-based studies, it often comes down to lack of opportunity in the formal economy because of inadequate hours, dehumanizing work conditions, or low wages.[xxv] For these interviewees, criminalized activity is a way of making ends meet.

Many of the economic roadblocks that can leave people with few options in the formal economy emerge long before a person enters the labor market. Children who grow up amid economic insecurity are more likely to experience traumatic stress and anxiety that can affect brain development.[xxvi] Research shows that children in low-income families are more likely to exhibit biological stress markers such as higher blood concentration of stress hormones and elevated resting blood pressure—and that these effects on the body can make it harder to succeed in school and beyond. Ultimately, men who grew up in a low-income family are about 20 times more likely to be incarcerated than those who grew up in a wealthy family.[xxvii]

Low income is far from the only roadblock that can lead to increased incarceration, though inadequate resources can make other barriers even more daunting. Research shows that having a serious psychiatric condition or a substance use disorder, experiencing domestic violence, and experiencing homelessness are all linked to a higher likelihood of later being incarcerated.[xxviii]

These roadblocks can affect people of every background and residents of every part of our state. At the same time, centuries of discriminatory policy choices have disproportionately forced Marylanders of color to face circumstances that can lead to incarceration.

- Decades of deliberate racial segregation continue to limit the options available to Marylanders of color when deciding where to live, including families with moderate or high incomes. For example, Black families with annual income between $100,000 and $125,000 on average live in neighborhoods with lower incomes and higher poverty rates than white families with income between $60,000 and $75,000.[xxix] Independent of an individual family’s income, research links hardship in a child’s neighborhood to involvement with the criminal legal system later in life.[xxx]

- Transportation policy choices can compound the harm done by residential segregation. For example, Black Marylanders have longer average commutes to work than their white counterparts. The difference is widest in areas of our state where workers of color live in the highest numbers.[xxxi] In some areas, Black workers commute up to 55 hours more each year than their white neighbors. Lack of geographic access to jobs is associated with a higher likelihood of participating in criminalized activity.

- Cutbacks in public school funding since the onset of the Great Recession have made it harder for children of color in Maryland to get a great education that can set them up for success in adulthood. As of 2017, more than half of Black students in Maryland went to school in a district that was underfunded by 15 percent or more compared to state standards—which are themselves inadequate to meet today’s academic expectations. Only about one in 12 white students went to school in a district this deeply underfunded.[xxxii]

- For many Marylanders of color, even a good education is no guarantee of steady work or good wages. At all educational levels, Black men in Maryland are less likely to be employed than their white counterparts, while Latinx and Asian men are employed at higher levels.[xxxiii] White, Latinx, and Asian women are less likely to be employed than their male counterparts, while Black women are employed at slightly higher rates than Black men. Well-designed research has linked these outcomes to hiring discrimination by employers.

- Racism can also limit the types of jobs workers have access to. Workers of color are more likely than white workers to be overqualified for their job, indicating that they face greater barriers to get a job that matches their qualifications.[xxxiv] For example, Black men in Maryland who have a bachelor’s degree are twice as likely as their white counterparts to have a job predominantly filled by high school graduates, while Latinx men are three times as likely to. Largely the same pattern plays out among women.

- Even workers who obtain a job that matches their qualifications often face additional, lopsided barriers. For example, white men with a bachelor’s degree who work at a bachelor’s-level job on average take home $124,000 per year, while similarly situated men of color earn between $89,000 (Black men) and $109,000 (Asian men).[xxxv] Across racial and ethnic groups, average earnings for women with a bachelor’s degree are less than $90,000.

Taken together, the array of economic roadblocks placed in front of Black and Brown Marylanders through policy choices can limit opportunities, make it harder to afford necessities, and for some, leave few options outside the underground economy.

Punitive legal policies act as a pipeline to incarceration

Harmful policy choices can also increase incarceration through punitive laws that put more people behind bars and keep them there longer.

- Policymakers have chosen to criminalize many activities people turn to for income when they have few options in the formal economy—from asking for help paying bus fare to sex work or drug sales. The decision to define these activities as crimes leads to responses such as incarceration that further destabilize a person’s life rather than offer alternative ways to make a living.

- Our legal system includes multiple features that effectively criminalize poverty.[xxxvi] For example, fines that might merely inconvenience a wealthy individual have a much greater impact for someone who is already struggling to afford the basics—meaning that even a small matter such as a traffic stop can eat into money needed to pay rent or buy groceries. If a person cannot afford to pay a fine, punitive policy responses such as driver’s license suspension can then force a person to choose between driving illegally and losing their job. Such policy choices can push someone onto a path that leads to incarceration.

- If a person is accused of a crime, multiple factors in our criminal legal system can render the promise of due process meaningless. Cash bail forces people with few resources to either take on unaffordable debt or accept pretrial detention, effectively punishing them for a crime of which they have not been convicted and potentially costing them their job.[xxxvii] This—combined with prosecutors’ documented practice of requesting draconian sentences in cases that go to trial[xxxviii]—creates a strong incentive to accept a plea agreement, even potentially for a crime the person did not commit.[xxxix] Maryland’s underfunded public defense system makes it even harder to get a fair trial, with a 2018 analysis finding the Office of the Public Defender would need an additional 109 positions (12 percent over the actual staffing level) to perform effectively.[xl] Combining all these factors, only about 5 percent of people accused of a crime nationwide exercise their right to proof beyond a reasonable doubt in a jury trial.[xli]

- Sentencing policy is one of the greatest contributors to mass incarceration in Maryland and nationwide. Draconian sentencing laws, including mandatory minimum sentences, drove the explosive increase in incarceration in Maryland and nationwide that took off in the 1970s.[xlii] Sentencing policy is also an important reason why incarceration rates in the United States are so far above the international norm. Courts in the United States are more than seven times as likely to sentence a person convicted of a crime to incarceration as courts in England and Wales, according to a 2011 analysis, and nearly 10 times as likely as courts in Germany and Finland.[xliii] Sentence duration is also exceptionally long in the United States. Average sentences for drug offenses are 66 percent longer in the United States than in England and Wales, and more than twice as long as in sentences in Finland. Sentences for robbery are more than twice as long in the United States as in England and Wales and more than five times as long here as in Finland.

- While a high degree of external control is a defining feature of incarceration, parole restores a degree of agency by creating a link between a person’s actions while incarcerated and the length of their confinement. However, Maryland law today allows the governor to reverse Maryland Parole Commission’s decision to grant parole at will, denying a person freedom in spite of the commission’s judgment. Even once a person is in the community on parole, they can still be reincarcerated for a technical violation (that is, one that does not involve a new criminal charge).[xliv] One in four admissions to Maryland prisons and jails in 2017 were for parole violations, and in 2018 more than 500 Marylanders were incarcerated on any given day for technical parole violations.[xlv]

When a person returns to the community from incarceration, the interaction of harmful economic and legal policies can make it even harder to stay out of prison:

- While Maryland has taken some positive steps to limit the practice in recent years, companies are still allowed to ask about applicants’ criminal record as part of the hiring process. This practice further narrows a person’s economic opportunities after incarceration, even for jobs unrelated to their prior conviction.

- State licensure rules further limit opportunities by disqualifying people with prior convictions for some occupational licenses, including for occupations unrelated to a person’s specific conviction. With fewer job opportunities in the formal economy, these barriers can leave previously incarcerated people little choice but to make ends meet through criminalized activity.

- Counterproductive rules prohibit people with prior convictions from using some economic security benefits, such as housing assistance. The added strain of having to scramble to meet basic needs—or being unable to meet those needs, such as if a person experiences homelessness—can get in the way of a successful job search and increase the urgency of finding any available source of income.

- Inadequate access to evidence-based approaches to substance use disorders, such as medication-assisted treatment—both in prison and after release—can make it harder to avoid relapse and as a result increase the risk of returning to prison.[xlvi] As of 2018, medication-assisted treatment is available temporarily to people detained at the Baltimore Pre-Trial Complex, and the state was conducting small-scale pilot programs elsewhere.[xlvii] However, this left the majority of incarcerated Marylanders without access to evidence-based treatment.

Because of these and other factors, people often struggle to find decent work after returning to the community. Less than half of people who are released from prison nationwide report any income from a job in the year of their release, and only about 60 percent report job-related income in the following year.[xlviii] Less than half of those who do find a job take home more than $15,000 per year.

Mass incarceration produces community-wide harms as well, many of which can perpetuate criminalized activity rather than reduce it. Families with a member who is incarcerated experience severe disruption through destabilized relationships and lost income, jeopardizing families’ access to necessities like food and housing and subjecting children to physiologically taxing trauma. Smaller and more transient neighborhood populations reduce sales at local businesses, making the neighborhood less attractive for investment and eroding the number of jobs available. Research links these collateral harms to a higher future likelihood of residents—especially children—engaging in criminalized activity and being incarcerated in the future.[xlix]

Mass Incarceration Doesn’t Make Communities Safer

The policy choices that have filled Maryland prisons over the last 50 years are premised on the assumption that locking up thousands of predominantly Black and Brown Marylanders will make communities across our state safer. But the best evidence—especially studies published since the turn of the century that use methods intended to establish causation—shows that this assumption is false:

- California enacted two major reform policies in 2011 and 2014 in response to court orders to reduce prison and jail overcrowding. Multiple independent analyses of these reforms find that the measures returned thousands of Californians to the community in a short period of time, with little to no negative effects. Studies published in 2016, 2018, and 2019 found no increase in serious crimes such as homicide, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, or burglary after these reforms.[l] These analyses did find a small increase in auto theft.

- A 2017 study used administrative data to track involvement with the criminal legal system among Florida youth before and after their 18th birthday.[li] Because adults 18 and over face potentially much more severe sentences for a given offense than adolescents, if severe sentencing were effective there would be a sharp decrease in arrests after a person’s 18th birthday as they change their behavior to avoid incarceration. The study found no such drop, indicating that the threat of much more severe sanctions after the 18th birthday did not reduce these individuals’ criminalized activity.

- A major literature review published in 2017 found mixed but generally weak evidence that long prison sentences reduce criminalized activity.[lii] The review also found that evidence suggests job opportunities are more important for determining the level of criminalized activity than sentencing policy. The authors concluded, “Within the range of typical changes to sanctions in contemporary criminal-justice systems, the evidence suggests that the magnitude of deterrence owing to more severe sentencing is not large.” Because of this, “it may be possible to reduce the size of the US prison population, which has grown six-fold over the course of a generation, without compromising public safety.”[liii]

Prison Magnifies Incarcerated Marylanders’ Existing Challenges

Maryland’s criminal legal policies should aim to strengthen safe communities and change the social conditions that generate criminalized activity. Instead, mass incarceration simply magnifies many of the challenges that pushed people toward incarceration in the first place.

While a full accounting of the damage done by mass incarceration is beyond the scope of this report, two aspects of incarcerated Marylanders’ experience—work and health care—shed light on why incarceration worsens rather than mitigates the challenges that can lead a person to engage in criminalized activity.

Work

In principle, work could be a positive part of incarceration. Most people in prison faced daunting challenges in the labor market prior to incarceration, and work opportunities in prison could be an opportunity to develop new skills, earn a decent income, and reduce the monotony that characterizes incarcerated life. However, in reality prison labor in Maryland largely serves to hide the fiscal cost of incarceration and extract value from incarcerated workers without anything resembling fair compensation. This is the natural result of a criminal legal system with historical roots in slavery and an explicit constitutional license to use forced labor as punishment.

There are two main structures through which incarcerated Marylanders can work:

- Maryland Correctional Enterprises (MCE) employs a minority of incarcerated workers to produce equipment and materials that are sold to other state agencies, such as office furniture, license plates, and, recently, protective equipment for workers during the pandemic.[liv] Incarcerated workers in the program produced $52 million worth of goods in fiscal year 2019. MCE is a comparatively more beneficial work option for incarcerated Marylanders, paying higher wages and offering more opportunities for skill development. In fiscal year 2017, MCE employed 2,042 incarcerated workers, about 10 percent of the state’s prison population.[lv] However, the state has cut back MCE operations since 2017 in response to staff shortages. By FY 2019, only 1,516 incarcerated workers were employed by MCE, a 26 percent drop since 2017.

- The majority of incarcerated workers contribute to daily prison operations. Work assignments are compulsory for incarcerated Marylanders who are eligible to work and offer lower wages than MCE. While work itself can in principle be a comparatively positive part of an incarcerated person’s experience, requiring incarcerated people to do work that is necessary for prison operations for meager pay is far from this ideal. In fiscal year 2019, 11,726 incarcerated Marylanders had non-MCE work assignments.[lvi]

The work incarcerated Marylanders do is real work that generates real value. If incarcerated workers did not do these jobs, the state would have to employ additional workers to do them. Yet the state pays incarcerated workers deeply inadequate wages for the value they produce.

| Table 2. Maryland Incarcerated Worker Wages, FY19 | ||||||

| Wage | % of Minimum Wage ($10.10, calendar year 2019) | |||||

| Lowest Wage | Illustrative Intermediate Wage | Highest Wage | Lowest Wage | Illustrative Intermediate Wage | Highest Wage | |

| MCE

(Hourly) |

$0.17 | $0.35 | $1.16 | 1.7% | 3.5% | 11.5% |

| Ordinary Work Assignments

(Daily) |

$0.90 | $1.15 | $2.75 | |||

| Hourly Equivalent (Assumes six-hour workday) | $0.15 | $0.19 | $0.46 | 1.5% | 1.9% | 4.5% |

| Wage data from Maryland Correctional Enterprises and DPSCS annual reports. Six-hour workday assumption based on Sawyer, 2017 | ||||||

Ultimately, these substandard wages use economic deprivation as a punishment for people whose incarceration is often the result of economic insecurity, which is in turn linked to discriminatory and racist policies.

Health Care

People in prison are much more likely to experience significant health problems than the general population. This is due in large part to the combined health impacts of racist policies and economic insecurity, as well as policy choices that directly or indirectly criminalize people with health problems.

- A 2009 study found that about 15 percent of men and 31 percent of women in a sample of Maryland and New York jails had a serious psychiatric condition.[lvii]

- Research has found that up to two-thirds of incarcerated adults live with a substance use disorder.[lviii]

- Research by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found that people with disabilities on average receive sentences 15 months longer than others convicted of the same offense.[lix]

- Between 2001 and 2016, 925 people died while incarcerated in Maryland prisons. Most of these deaths were due to causes that are common among the general population, such as heart disease and cancer. However, disproportionate numbers of incarcerated Marylanders died of causes associated with extraordinary health issues:[lx]

- 11 percent of deaths were related to HIV, compared to 0.9 percent of mortality among all Marylanders.

- 7 percent of deaths were by suicide, compared to 1.2 percent of statewide mortality.

- 6 percent of deaths were related to alcohol or drug intoxication, compared to 3 percent of mortality among the general population.

Courts have ruled that prisons in the United States are constitutionally required to provide a minimally adequate standard of medical care. But any truly just criminal legal system must provide incarcerated people health care of equal quality to that available to people in the community and must effectively meet incarcerated people’s specific health needs. Moreover, effectively addressing incarcerated Marylanders’ health needs is an essential step to prepare incarcerated people to thrive when they return to the community and avoid later involvement with the criminal legal system.

Our current system falls far short of these standards, in regard to both access and quality.

Copays Are a Barrier to Health Care Access

Copays can pose a significant barrier to accessing needed care. Because people in prison typically have low incomes before they are incarcerated, a large share of people in Maryland prisons would likely be eligible for Medicaid if they were not incarcerated—meaning they would pay no copay for doctor’s visits or medical procedures.[lxi] However, Maryland prisons charge a $2 copay for most medical services.[lxii] Although this is lower than copays in most private insurance plans, it can pose a significant challenge in light of the miniscule wages incarcerated workers are able to earn. For example, an incarcerated worker in a position classified as skilled who is at step 2 of the pay scale currently earns $1.38 per day. This means that a doctor’s visit would cost this person 1.45 days’ pay. Assuming a six-hour workday,[lxiii] for a person earning the 2020 minimum wage of $11 per hour, this is equivalent to a $96 copay. For comparison, the average copay for a primary care visit in employer-based health insurance plans was $25 in 2019.

If the incarcerated worker in this example would have been eligible for Medicaid outside of prison, this onerous copay effectively creates a barrier to accessing health care as a punishment.

|

Table 3. Prison Copays in the Context of Prison Wages |

||||

| Work Assignment | Daily Pay Rate | Hourly Pay Rate

(Or Hourly Equivalent) |

Time Required to Earn $2 | Equivalent Copay for a Worker Earning $11 per Hour |

| Ordinary

“Unskilled” Step 1 |

$1.08 | $0.18 | 1.85 workdays | $122 |

| Ordinary

“Skilled” Step 2 |

$1.38 | $0.23 | 1.45 workdays | $96 |

| Ordinary

“Craftsman” Step 4 |

$3.30 | $0.55 | 0.61 workdays | $40 |

| MCE

Safety Inspector |

NA | $0.35 | 5.7 hours | $63 |

| MCE

Warehouse Team Leader |

NA | $1.16 | 1.7 hours | $19 |

Lack of Evidence-Based Drug Treatment Makes Recovery Harder

Most Maryland prisons do not offer medication-assisted addiction treatment at all, even though it is shown to be highly effective in preventing relapse and generally improving outcomes for people who are dependent on opioids. Offering evidence-based drug treatment would reduce suffering while people are in prison and reduce the likelihood of relapse once people are out, thereby reducing the likelihood of returning to prison.[lxiv]

Incarceration Unavoidably Poses a COVID-19 Risk

Protecting incarcerated Marylanders is more urgent than ever amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Prisons nationwide have been hot spots for COVID-19 infections and deaths. To date, the pandemic has killed 13 incarcerated Marylanders and two prison staff.[lxv] Although the virus has to date taken a smaller toll in Maryland prisons than elsewhere in the country, this pandemic has repeatedly shown that complacency can be deadly.

Maryland Has a Foundation to Build On

Maryland made national headlines two years ago when a report found the number of people confined in Maryland prisons declined by 10 percent, a steeper drop than in any other state. This was seen as sign that the state’s commitment to major reforms to its criminal legal system, like the Justice Reinvestment Act, are working.

In 2017, Maryland saw the largest decline of any state in both the number of people we incarcerate and the share of Marylanders who are in prison or jail – a 10 percent drop from 2016 and 28 percent below our 2007 incarceration rate.[lxvi] While the state did not repeat such sharp declines in subsequent years, Marylanders should be proud that our state has reduced its reliance on costly prisons nearly seven times as quickly as the rest of the country while also investing in more effective, common-sense solutions to maintain public safety.

Two recent judicial reforms have contributed to our declining prison population:

- The 2016 Justice Reinvestment Act reduced ineffective mandatory minimum penalties for minor offenses and modernized the way our parole and probation systems deal with technical violations. The law also reinvests the savings from reduced reliance on incarceration to increase access to addiction treatment, mental health care, and re-entry services—helping keep more people out of the criminal legal system.

- A 2017 ruling by the Maryland Court of Appeals curtailed the practice of keeping people accused of crimes in jail simply because they cannot afford to pay bail. Unaffordable bail pressures people who are often already struggling to make ends meet to plead guilty rather than sit in jail through an uncertain and potentially lengthy trial process. Reducing and ultimately eliminating the use of money bail is an important step in breaking Maryland’s poverty to prison pipeline and protecting due process.

These reforms represent important progress in rolling back the criminalization of poverty and harmful sentencing policies in Maryland, but they left much of these unjust systems intact:

- The Justice Reinvestment Act increased penalties for some offenses and made it easier for prosecutors to impose harsh sentences associated with purported “criminal enterprises.” These policies expand the scope of Maryland’s criminal legal system along with all the inequities it creates.

- Despite the reduction in use of cash bail, other criminal legal system fees and fines have a similar impact. When courts require people to wear GPS monitors while awaiting trial in the community, this surveillance can come with fees of up to $375 per week—and failure to pay could land a person in jail.[lxvii]

State policymakers continue to consider other reforms, from legalizing recreational cannabis to reforming local policing policies, that could further reduce incarceration. It is vital that these policy changes are carefully designed to both reverse the harms that our criminal legal system causes in Black and Brown communities and also make investments that remove barriers to opportunity in those communities.

Continuing to Build a Just System

Maryland will be better off if state policymakers continue to shift away from mass incarceration, which is costly and harmful, and invest more in family income supports and essential services that strengthen Maryland communities.

Major sentencing reform is the most important step to significantly decrease the number of people behind bars in Maryland. While sentencing reform was one component of the Justice Reinvestment Act, the law’s narrowly tailored approach can achieve only limited reductions in incarceration. Sentencing practices in the United States are out of step with international norms for minor and serious offenses alike. The best research shows that comprehensive sentencing reform is compatible with supporting safe communities.

Sentencing reforms should be applied retroactively to ensure no one currently in prison serves a longer sentence than is allowed under post-reform law. The state should also expedite implementation to reduce the imminent risk of COVID-19 outbreaks in prisons and jails.

A just and equitable approach also requires ending policies that effectively criminalize poverty, like criminal legal system fines and fees and driver’s license revocation. We must replace criminalization of work in the underground economy with effective, non-punitive alternatives.

We must also strengthen Marylanders’ right to due process when they are accused of a crime. This entails steps such as taking legislative action to fully implement bail reform, adequately funding and staffing the Office of the Public Defender, and requiring discovery before plea bargaining.

While it is no substitute for restoring incarcerated Marylanders’ freedom, we can take steps to improve conditions in prisons and jails, such as eliminating onerous copays and other fees, ensuring access to evidence-based drug treatment, guaranteeing incarcerated workers a fair wage, and granting incarcerated workers the right to join together and collectively negotiate the terms of their work.

And, we should strengthen incarcerated Marylanders’ ability to direct their own future through parole reform. We can do this by repealing the governor’s power to deny parole at will, establishing a defeasible presumption in favor of granting parole when an incarcerated person becomes eligible, and eliminating reincarceration for technical violations.

The state should do more to support formerly incarcerated Marylanders as they return to the community:

- Research shows that access to economic security benefits can help formerly incarcerated people avoid further involvement with the criminal legal system.[lxviii] We have taken some smart steps such as streamlining Medicaid enrollment post-incarceration, but formerly incarcerated people are not eligible for many benefits, such as housing assistance. We should ensure formerly incarcerated Marylanders are able to put food on the table and keep a roof over their head, using state dollars where federal funding is unavailable.

- We should invest in increasing the availability of evidence-based medication-assisted treatment to help prevent opioid relapse. This policy has the potential to reduce subsequent involvement with the criminal legal system and save lives.

- We should remove barriers that make it harder for formerly incarcerated workers to find a family-supporting job by eliminating criminal legal system involvement from the job application process (ban the box) and occupational licensure requirements. These policies may include narrow exemptions for cases when this information is directly relevant to job duties.

The state should at the same time take proactive steps to support safe, thriving communities. In light of the research linking scarce jobs and low wages to criminalized activity, increasing access to good jobs should take center stage. There is much work that needs to be done in Maryland—building affordable housing, updating our infrastructure, delivering basic services such as sanitation, and more—and thousands of workers who are ready to do it. One particularly promising avenue at a time when outdoor recreation options are vital to protecting public health is to convert vacant lots in disinvested neighborhoods into inviting parks. Randomized experimental studies (often considered the gold standard in social science research) have shown that this is an effective strategy for reducing neighborhood violence and other criminalized activity.[lxix]

These projects must come with strong worker protections to ensure good wages, benefits, and working conditions, and should safeguard workers’ right to organize. Research shows that high-quality jobs are needed to improve community safety. These projects must also include targeted hiring standards to ensure that they improve economic opportunity for residents of affected communities and dismantle the barriers that often push Black and Brown Marylanders into the criminal legal system.

Public- and private-sector worker protections are essential to improve job opportunities throughout Maryland. The state should invest more resources in enforcing wage, safety, and anti-discrimination standards, including proactive enforcement that does not rely on filed complaints.

Dismantling injustice in Maryland’s criminal legal system also requires the state to revamp its approach to performance measurement. The Managing for Results performance measurement system used in the state’s budget process today includes only minimal measures related to incarcerated Marylanders’ wellbeing. We should reform the system to measure outcomes such as incarcerated people’s physical and mental health and wages earned during and after incarceration. These measures should be disaggregated by race, ethnicity, gender, and other equity-relevant categories to ensure that our criminal legal system treats all Marylanders with dignity.

All of these reforms must be oriented toward the goal of increasing justice, not merely cutting costs. As we downsize Maryland’s prison system, expenditures will likely take time to fall, and a more equitable system will require investing in things like housing, health care, and good jobs that make it easier to stay out of prison. This can be done most effectively in a broader context of strong public investments in the foundations of strong communities, supported by an effective and equitable revenue system.

Endnotes

[i] Maryland State Archives and the University of Maryland College Park (2007). A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland. http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/intromsa/pdf/slavery_pamphlet.pdf

[ii] Jeremy Travis and Bruce Western ed., The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Causes and Consequences (Washington, D.C.: The National Academy Press, 2014). Available at http://johnjay.jjay.cuny.edu/nrc/NAS_report_on_incarceration.pdf

[iii] Khalil Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

[iv] Khalil Muhammad, “Why Police Accountability Remains Out of Reach,” The Washington Post, July 26, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/26/why-police-accountability-remains-out-reach/?noredirect=on

[v] Travis and Western, 2014.

[vi] Maryland and Nationwide incarceration data from the U.S. Census Bureau Statistical Abstract series (pre-1980; https://www.census.gov/library/publications/time-series/statistical_abstracts.html) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics data analysis tool (1980 onward; https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nps).

[vii] Unless otherwise noted, incarceration and community supervision data in this paragraph from Alexi Jones, “Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and Supervision by State,” Prison Policy Institute, 2018. Data appendix at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/correctionalcontrol2018_data_appendix.html

[viii] FY 2019 average daily population, based on Maryland Department of Juvenile Services Managing for Results data. FY 2019 includes December 31, 2018, the date used for most 2018 incarceration statistics.

[ix] Peter Wagner and Wendy Sawyer, “States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018,” Prison Policy Institute, 2018, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2018.html

This comprehensive measure of incarceration includes state and federal prisons, local jails, juvenile facilities, immigration detention, and other types of confinement.

[x] Wagner and Sawyer, 2018.

[xi] MDCEP analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics incarceration data and U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates for 2019. The share of people in state prisons who are Black is higher in Maryland than in any other state. This is driven both by racially disproportionate incarceration rates and by Maryland’s above-average share of all residents who are Black. Taking into account population composition, Maryland’s incarceration rates are more racially lopsided than the United States overall, but by most measures Maryland is not among the most lopsided states.

[xii] MDCEP analysis of juvenile confinement data from the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Residential placement rates are defined as a share of children ages 10 and older.

[xiii] Bureau of Justice Statistics 2018 incarceration data.

[xiv] Ilan Meyer, Andrew Flores, Lara Stemple, Adam Romero, Bianca Wilson, and Jody Herman, “Incarceration Rates and Traits of Sexual Minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012,” American Journal of Public Health 107, 2017, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303576

[xv] Sari Reisner, Zinzi Bailey, and Jae Sevelius, “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in History of Incarceration, Experiences of Victimization, and Associated Health Indicators Among Transgender Women in the U.S.,” Women & Health 54(8), 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5441521/

[xvi] Henry Steadman, Fred Osher, Pamela Robbins, Brian Case, and Steven Samuels, “Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness Among Jail Inmates,” Psychiatric Services 60(6), 2009, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19487344/

[xvii] Jennifer Karberg and Doris James, “Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2005, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/sdatji02.pdf

[xviii] Rachael Seevers, “Making Hard Time Harder: Programmatic Accommodations for Inmates with Disabilities Under the Americans with Disabilities Act,” AVID Prison Project, 2016,

http://avidprisonproject.org/Making-Hard-Time-Harder/assets/making-hard-time-harder—pdf-version.pdf

[xix] Thomas Bonczar, “Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974–2001,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/piusp01.pdf

Maryland-specific data on the number of who people who have ever been incarcerated are not available.

[xx] Peter Enns, Youngmin Yi, and Megan Comfort, “What Percentage of Americans Have Ever Had a Family Member Incarcerated? Evidence from the Family History of Incarceration Survey,” Socius 5, 2019, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023119829332

[xxi] MDCEP analysis of Prison Policy Institute 2010 incarceration data and American Community Survey 2008–2012 five-year estimates.

[xxii] Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner, “Work and Opportunity Before and After Incarceration,” The Brookings Institute, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/work-and-opportunity-before-and-after-incarceration/

[xxiii] Ryan King, “The Economics of Drug Selling: A Review of the Research,” The Sentencing Project, 2003, https://static.prisonpolicy.org/scans/sp/5049.pdf

[xxiv] For discussion of research documenting impacts of economic conditions on criminalized activity, see:

David Mustard, “How Do Labor Markets Affect Crime? New Evidence on an Old Puzzle,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 4856, 2010, http://ftp.iza.org/dp4856.pdf

Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary, “Criminal Deterrence: A Review of the Literature,” Journal of Economic Literature 55(1), 2017, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jel.20141147

Brian Beach and John Lopresti, “Losing by Less? Import Competition, Unemployment Insurance Generosity, and Crime,” Economic Inquiry 57(2), 2019, https://brianbbeach.github.io/Materials/Publications/2019_Losing_by_less_EI.pdf

[xxv] John Hagedorn, “Homeboys, Dope Fiends, Legits, and New Jacks,” Criminology 32(2), 1994, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1994.tb01152.x

John Hagedorn, “The Business of Drug Dealing in Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Policy Research Institute Report 11(5), 1998, https://www.csdp.org/research/drugdeal.pdf

[xxvi] Leila Morsy and Richard Rothstein, “Toxic Stress and Children’s Outcomes,” Economic Policy Institute, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/toxic-stress-and-childrens-outcomes-african-american-children-growing-up-poor-are-at-greater-risk-of-disrupted-physiological-functioning-and-depressed-academic-achievement/

[xxvii] Looney and Turner, 2018.

[xxviii] See endnotes xv to xix. See also:

Greg Greenberg and Robert Rosenheck, “Jail Incarceration, Homelessness, and Mental Health: A National Study,” Psychiatric Services 59(2), 2008, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18245159/

Dale McNiel, Renée Binder, and Jo Robinson, “Incarceration Associated with Homelessness, Mental Disorder, and Co-Occurring Substance Abuse,” Psychiatric Services 56(7), 2005, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16020817/

William Hawthorne, David Folsom, David Sommerfeld, Nicole Lanouette, Marshall Lewis, Gregory Aarons, Richard Conklin, Ellen Solorzano, Laurie Lindamer, and Dilip Jeste, “Incarceration Among Adults Who Are in the Public Mental Health System: Rates, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Outcomes,” Psychiatric Services 63(1), 2012, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22227756/

[xxix] MDCEP analysis of 2013–2017 American Community Survey five-year estimates.

[xxx] Corinne David-Ferdon and Thomas Simon, “Preventing Youth Violence: Opportunities for Action,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/youthviolence/pdf/opportunities-for-action.pdf

[xxxi] Christopher Meyer, “Budgeting for Opportunity: How our Fiscal Policy Choices Can Remove Barriers Facing Marylanders of Color and Advance Shared Prosperity,” Maryland Center on Economic Policy, 2018, http://www.mdeconomy.org/budgeting-for-opportunity/

[xxxii] MDCEP analysis of funding adequacy data from Department of Legislative Services July 24, 2019, presentation to the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Funding Formula Workgroup (http://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/NoPblTabMtg/CmsnInnovEduc/2019_07-24_AdequacyDLS.pdf) and enrollment data by race and ethnicity from the National Center for Education Statistics.

[xxxiii] MDCEP analysis of 2013–2017 IPUMS American Community Survey microdata. The purpose of comparing employment outcomes among Black, Latinx, and Asian workers to those of white workers is to contrast the impacts of racist systems and policies on groups who are marginalized in those systems to those whom the systems exist to benefit. This comparison does not aim to establish white workers as a standard or norm to which other groups should aspire, but rather to demonstrate the benefits racist systems generate for white people and deny to people of color.

[xxxiv] MDCEP analysis of 2013–2017 IPUMS American Community Survey microdata.

See also Jhacova Williams and Valerie Wilson, “Black Workers Endure Persistent Racial Disparities in Employment Outcomes,” Economic Policy Institute, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/labor-day-2019-racial-disparities-in-employment/

[xxxv] MDCEP analysis of 2013–2017 IPUMS American Community Survey microdata.

[xxxvi] Lavanya Madhusudan, “The Criminalization of Poverty: How to Break the Cycle through Policy Reform in Maryland,” Job Opportunities Task Force, 2018, https://jotf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/cop-report-013018_final.pdf

[xxxvii] See discussion of cash bail in Madhusudan, 2018.

[xxxviii] “The Trial Penalty: The Sixth Amendment Right to Trial on the Verge of Extinction and How to Save It,” National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 2018, https://www.nacdl.org/getattachment/95b7f0f5-90df-4f9f-9115-520b3f58036a/the-trial-penalty-the-sixth-amendment-right-to-trial-on-the-verge-of-extinction-and-how-to-save-it.pdf

[xxxix] Paul Heaton, Sandra Mayson, and Megan Stevenson, “The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pretrial Detention,” Stanford Law Review 69, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2809840

[xl] David Juppe, Sierra Boney, Patrick Frank, Andrew Gray, Garret Halbach, Lindsey Holthaus, Jason Kramer, Steven McCulloch, Jorden More, Rebecca Ruff, Jody Sprinkle, Jared Sussman, Laura Vykol, Ken Weaver, Benjamin Wilhelm, and Tonya Zimmerman, “Executive Branch Staffing Adequacy Study,” Department of Legislative Services, 2018, http://dls.maryland.gov/pubs/prod/TaxFiscalPlan/Executive-Branch-Staffing-Adequacy-Study.pdf

[xli] See Brian Reaves, “Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009 – Statistical Tables,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fdluc09.pdf and Sean Rosenmerkel, Matthew Durose, and Donald Farole, “Felony Sentences in State Courts, 2006 – Statistical Tables,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fssc06st.pdf

Reaves, 2013, found that only 2 percent of felony cases in large urban counties nationwide ended in conviction by a jury and 1 percent ended in acquittal. Excluding the 25 percent of cases that were dismissed, trial convictions and acquittals amount to 4 percent of cases.

Rosenmerkel et al., 2009, found that pleas accounted for 94 percent of felony convictions in state courts.

[xlii] Travis and Western, 2017.

[xliii] Amanda Petteruti, “Finding Direction: Expanding Criminal Justice Options by Considering Policies of Other Nations,” Justice Policy Institute, 2011, http://www.justicepolicy.org/research/2322

[xliv] The 2016 Justice Reinvestment Act made improvements to the state’s parole process, but still allows incarceration for technical violations in some circumstances.

[xlv] MDCEP analysis of data from the Council of State Governments Justice Center, “Confined and Costly: How Supervision Violations Are Filling Prisons and Burdening Budgets,” 2019, https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/confined-costly/?state=MD#primary

[xlvi] Sarah Wakeman, “Why it’s Inappropriate Not to Treat Incarcerated Patients with Opioid Agonist Therapy,” APA Journal of Ethics 19(9), 2017, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-its-inappropriate-not-treat-incarcerated-patients-opioid-agonist-therapy/2017-09

Ingrid Binswanger, Marc Stern, Richard Deyo, Patrick Heagerty, Allen Cheadle, Joann Elmore, and Thomas Koepsall, “Release from Prison—A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates,” New England Journal of Medicaine 356(2), 2007, https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsa064115

Michael Gordon, Timothy Kinlock, Robert Schwartz, and Kevin O’Grady, “A Randomized Clinical Trial of Methadone Maintenance for Prisoners: Findings at 6 Months Post-Release,” Addiction 103(8), 2008, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.002238.x

Maddy Troilo, “We Know How to Prevent Opioid Overdose Deaths for People Leaving Prison. So Why Are Prisons Doing Nothing?” Prison Policy Institute, 2018, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2018/12/07/opioids/

[xlvii] German Lopez, “How America’s Prisons Are Fueling the Opioid Epidemic,” Vox, 2018, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/13/17020002/prison-opioid-epidemic-medications-addiction

[xlviii] Looney and Turner, 2018.

[xlix] David-Ferdon and Simon, 2014.

[l] Magnus Lofstrom and Steven Raphael, “Incarceration and Crime: Evidence from California’s Public Safety Realignment Reform,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 664(1), 2016,https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716215599732

Jody Sundt, Emily Salisbury, and Mark Harmon, “Is Downsizing Prisons Dangerous? The Effect of California’s Realignment Act on Public Safety,” Criminology & Public Policy 15(2), 2016, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9133.12199

Bradley Bartos and Charis Kubrin, “Can We Downsize our Prisons and Jails without Compromising Public Safety? Findings from California’s Prop 47,” Criminology & Public Policy 17(3), 2018,https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9133.12378

Patricio Dominguez-Rivera, Magnus Lofstrom, and Steven Raphel, “The Effect of Sentencing Reform on Crime Rates: Evidence from California’s Proposition 47,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 12652, 2019, http://ftp.iza.org/dp12652.pdf

[li] David Lee and Justin McCrary, “The Deterrence Effect of Prison: Dynamic Theory and Evidence,” Regression Discontinuity Designs 38, 2017, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/S0731-905320170000038005/full/html

[lii] Chalfin and McCrary, 2017

[liii] Chalfin and McCrary, 2017

[liv] Maryland Correctional Industries FY 2019 Annual Report, https://mce.md.gov/Portals/0/PDF2020/Annual%20Report%202019_1.pdf

[lv] Maryland state prisons confined 19,821 people as of December 31, 2016, the midpoint of FY 2017.

[lvi] Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services Division of Correction Annual Report, FY 2019, http://dlslibrary.state.md.us/publications/Exec/DPSCS/DOC/COR3-207(d)_2019.pdf

[lvii] Steadman et al., 2009.

[lviii] Karberg and James, 2005.

[lix] Seevers, 2016.

[lx] MDCEP analysis of prison mortality data from Ann Carson and Mary Cowhig, “Mortality in State and Federal Prisons, 2001–2016 – Statistical Tables,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2020, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/msfp0116st.pdf and statewide mortality data from Maryland Vital Statitics 2001–2016 annual reports.

[lxi] Tricia Brooks, Lauren Roygardner, Samantha Artiga, Olivia Pham, and Rachel Dolan, “Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2020: Findings from a 50-State Survey, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicaid-and-CHIP-Eligibility,-Enrollment-and-Cost-Sharing-Policies-as-of-January-2020.pdf

See Table 19. Copays for prescription drugs range from $1 to $3.

[lxii] Wendy Sawyer, “The Steep Cost of Medical Mo-Pays in Prison Puts Health at Risk,” Prison Policy Institute, 2017, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/19/copays/

[lxiii] A 2017 analysis of prison wages by the Prison Policy Institute assumed a 6.35-hour workday for regular prison jobs and a 6.79-hour workday for enterprise jobs. Hourly wage estimates are somewhat higher using our 6-hour assumption. See Wendy Sawyer, How Much Do Incarcerated People Earn in Each State?” Prison Policy Institute, 2017, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/10/wages/

[lxiv] See endnote xxxii.

[lxv] Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services COVID-19 Data Dashboard, https://news.maryland.gov/dpscs/covid-19/

[lxvi] Oliver Hinds, Jacob Kang-Brown, and Olive Lu, “People in Prison in 2017,” Vera Institute of Justice, 2018, https://www.vera.org/publications/people-in-prison-in-2017

[lxvii] Tim Prudente, “They’ll Have their Day in Maryland Court. But Coronavirus Means a Long Wait, Big Fees for Ankle Monitoring.” The Baltimore Sun, August 28, 2020, https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-ci-cr-home-detention-coronavirus-20200828-aqhhndiaereorga6246jjnywqe-story.html

[lxviii] Joseph Morrissey, Gary Cuddeback, Alison Cuellar, and Henry Steadman, “The Role of Medicaid Enrollment and Outpatient Service Use in Jail Recidivism Among Persons with Severe Mental Illness,” Psychiatric Services 58(6), 2007, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17535939/

[lxix] Charles Branas, Eugenia South, Michelle Kondo, Bernadette Hohl, Philippe Bourgois, Douglas Wiebe, and John MacDonald, “Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial to Restore Blighted Vacant Land and its Effects on Violence, Crime and Fear,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(2), 2018, https://www.pnas.org/content/115/12/2946

Eric Klinenberg, “The Other Side of ‘Broken Windows,’” The New Yorker, August 23, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-other-side-of-broken-windows