On the Ballot: Vote Against Montgomery County Question B for a Strong Future

Montgomery County is one of just four jurisdictions in the state that have artificial restrictions on how much revenue from property taxes can grow in a given year. These revenue caps impose rigid limits on how much a county can invest in the building blocks of prosperity like good schools, transit services, and safe roads.

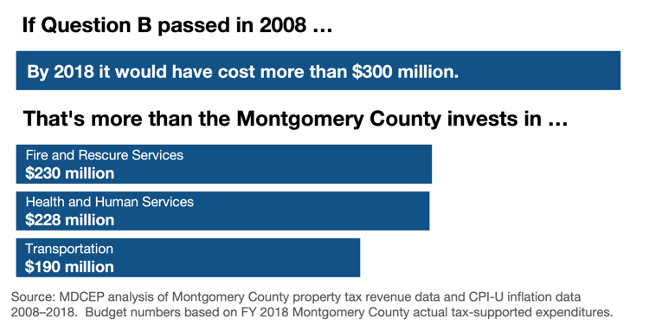

A proposed amendment to the county charter would make the existing cap even stricter, putting at risk the county’s ability to invest in vital public services at a time when local officials are working hard to address the challenges of the coronavirus pandemic. To ensure Montgomery County residents retain the flexibility to invest in public health, schools, parks, emergency services, transportation, libraries, and other community priorities, voters must reject Question B.

Under the current system county residents still exercise control over the county’s fiscal priorities through elections and the annual budget process, while maintaining flexibility that helps the county respond to crises and invest in its future. In the long term, removing revenue caps altogether is the best approach for Montgomery County and the other jurisdictions that have them.

How the Cap Works

Maryland counties tax real property, like land and buildings, as well as personal property, like equipment owned by businesses. The revenue cap applies to the real property tax, which is the single most important local source of revenues for funding the county’s schools, libraries, parks, and other county services.

Two factors determine property tax revenue: the tax base, or the total value of all taxable land and buildings in the county, and the tax rate. Montgomery County’s real property tax rate for the current budget year is 69.48 cents per $100 in property value, its lowest level in the last five years. Municipalities and special taxing districts in the county fund local services with additional property taxes, with three-quarters of sub-county jurisdictions levying between 1 cent and 30 cents per $100 property value.

The current cap specifies that property tax revenue cannot increase by more than the previous year’s increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the most common inflation measure for household consumption. The County Council can override the cap with a unanimous vote. Question B would eliminate the council’s ability to override the cap.

There is one situation in which revenue growth is allowed to exceed the cap. A 2012 state law allows counties with revenue caps to exceed those caps if the entire increase is appropriated to the local school district. This law comes with stringent requirements. If a county exceeds its revenue cap to fund schools, it is not allowed to reduce school funding from any other source and must report the action to the governor and the General Assembly. This means that county governments cannot exceed revenue caps to fund other public services like road repairs or fire protection.

Three other Maryland counties have similar caps on real property tax revenue:

- Anne Arundel County: Revenue growth may not exceed CPI growth or 4.5 percent, whichever is less.

- Talbot County: Revenue growth may not exceed CPI growth or 2 percent, whichever is less.

- Wicomico County: Revenue growth may not exceed CPI growth or 2 percent, whichever is less.

Lessons from Colorado

The stricter revenue cap Montgomery County would face if Question B passes is similar in many respects to the so-called “Taxpayer Bill of Rights” that has been law in Colorado since 1992. Colorado caps property tax revenue using a formula based partly on the Consumer Price Index. However, Colorado’s cap also incorporates population growth, so that revenues can increase as a larger population increases the need for public services. The proposed changes under Question B would not account for a growing county population.

Colorado’s revenue cap has caused significant problems for the state:

- Without sufficient revenues to fully fund education, Colorado’s investments in public schools and higher education fell behind other states in the years after it enacted the cap.

- The state was forced to cut back on essential public health programs like vaccinations because of inadequate revenue, threatening public health and potentially increasing medical costs.

- Credit agencies downgraded the state’s bond rating in 2002, partly because the revenue cap makes it more likely that the state will default on its debt. This can make it more expensive to construct public facilities.

Thanks in large part to Colorado’s poor performance under the revenue cap, 30 other states have rejected similar measures, despite persistent lobbying campaigns. Colorado itself temporarily suspended its cap in 2005 in order to strengthen its public investments—a goal that was undermined by the Great Recession.

Colorado’s experience shows that placing arbitrary limits on local revenue is a misguided strategy. Meanwhile, the majority of Maryland counties that do not impose these rigid rules still show a record of fiscal responsibility. For the sake of a bright future in Montgomery County, voters must reject Question B.