Maryland’s Tax Policy Has Improved, But Still Falls Short of Meeting Our State’s Needs

The investments we make through our taxes support the schools, roads, parks, and other things that help our communities thrive, but our upside down tax code means that not everyone is equally sharing in that responsibility. As a result of our tax structure and loopholes inserted into our tax system by special interests, our state doesn’t have the resources to make much-needed investments that would strengthen our communities and increase the quality of life for all Marylanders.

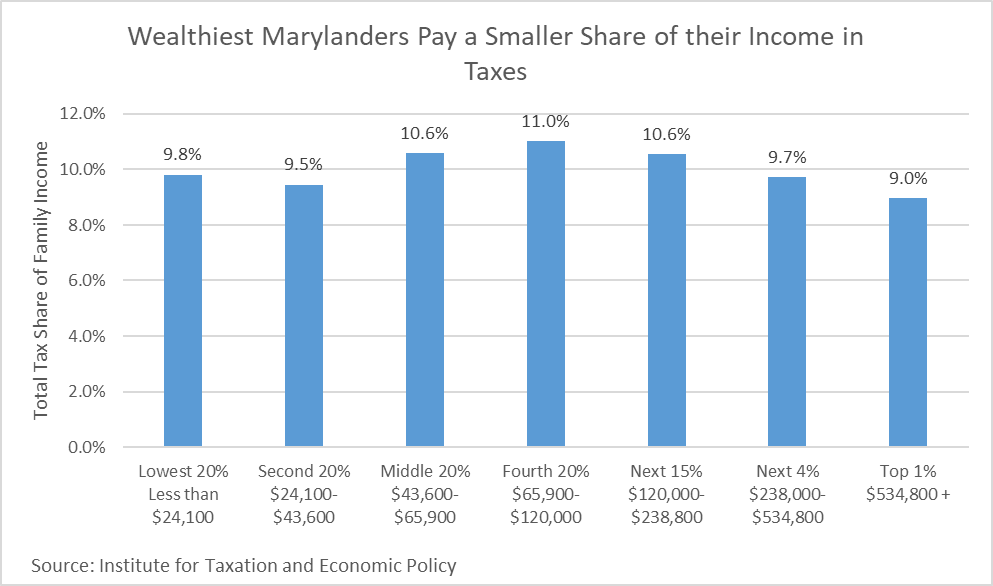

New analysis from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) shows that those earning the most in Maryland pay the lowest share of their income in state and local taxes. As a share of their income, the poorest 20 percent of taxpayers – those earning less than $24,100 per year – pay 1.1 times as much in taxes as the wealthiest 1 percent, those earning more than $534,000 per year.

Like the vast majority of the country, Maryland ranks negatively on ITEP’s latest tax inequality index, indicating that residents with low and moderate incomes pay a larger share in taxes than wealthy residents, and that our tax code worsens income inequality rather than improving it. Much of the fairness in state tax policy depends on the reliance on different tax systems. Sales and excise taxes, as well as property taxes, tend to be put the greatest responsibilities on families who already struggle to afford the basics. Within Maryland, those in the top 1 percent make over $534,000 per year, and pay the least in sales and excises taxes, at 0.7 percent of their income, compared to the poorest 20 percent, who earn less than $24,100 and pay 5.9 percent of their income in sales and excise taxes.

However, there is much Maryland does right in regards to its tax policy. Maryland currently employs a graduated rate income tax structure. This means that higher tax rates are applied at higher income levels, which helps ensure that everyone pays their fair share for state services. We also have an Earned Income Tax Credit, which helps ensure people who work hard for low pay aren’t taxed further into poverty. The EITC helps reduce poverty and income inequality within Maryland. In the last legislative session, Maryland policymakers strengthened the EITC by eliminating the minimum age limit (previously set at age 25) increasing access to this effective anti-poverty tool for younger workers who don’t claim dependent children.

Other positive features of Maryland’s tax code include the exclusion of groceries from the sales tax, which helps low-income families and seniors on a fixed income afford food. Maryland also has a state estate tax and county inheritance tax, which are typically paid by people receiving multi-million-dollar inheritances. Unfortunately, due to changes over the last several years that eroded the estate tax’s role in raising state revenue, Maryland’s estate tax now exempts all estates valued at less than $5 million. That means less than 1 percent of estates would ever pay the tax.

As a result of these policies, and sometimes in spite of them, Maryland is doing a better job than most other states in creating a fair tax system. According to the ITEP report, Maryland is one of the 10 least regressive states in the nation thanks to the choices we have made. However, the fact remains that our tax code places a higher burden on those who can least afford it and does not raise enough revenue to support thriving communities across the state.

To raise the additional revenues we need for our schools, roads, transit services, and other things that make Maryland a good place to live and work will take additional attention to our tax code. As a starting point, policymakers should close loopholes in the state’s corporate income tax. For example, they should adopt combined reporting as part of the state’s corporate income tax, in which a business composed of a parent corporation and one or more subsidiaries is treated as a single corporation for tax purposes. Doing so would nullify multiple tax-avoidance strategies by multistate corporations.