We Must Keep our Promises to the Low-Wage Workers who Keep Maryland Communities Going

The coronavirus pandemic has shone a light on Maryland communities’ deep reliance on the workers who keep families fed, care for aging adults, and maintain sanitary public spaces. Yet these same workers too often take home wages that cannot support a family, let alone compensate for the daily risks their jobs require. As policymakers respond to the growing economic crisis, they must recognize the need to support the essential workers who support the rest of us. This means strengthening basic protections like the minimum wage and the right to earn paid sick days—not walking back the promises they have already made. Freezing Maryland’s minimum wage at its current, inadequate level would harm the very people now holding up our communities, weaken Maryland’s economy, and ultimately make us all worse off:

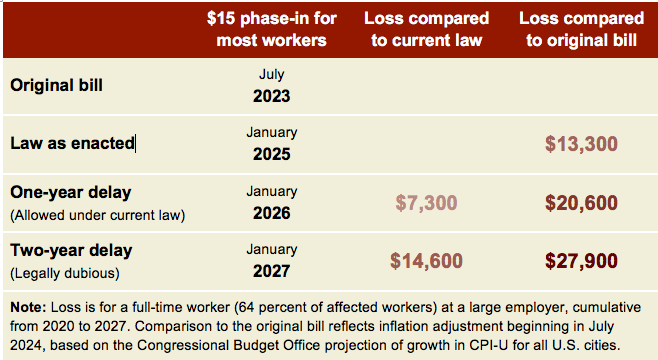

- Freezing the minimum wage would cost a typical low-wage worker more than $7,000 in lost wages by 2025, even as basics like housing and health care continue to become more unaffordable. A proposed—though legally dubious—two-year freeze would cost a typical worker well over $14,000 by 2026.

- Freezing the minimum wage would do outsized harm to women and workers of color who are overrepresented in low-wage jobs.

- Freezing the minimum wage would depress consumer spending and weaken Maryland’s economy for years to come.

Further, corporate lobbyists’ recent claims about ignore the best research on the economics of the minimum wage.

Maryland’s Coronavirus Response Must Reflect our Values

The most important goal of economic policy is to ensure that all Marylanders are able to meet their basic needs and live with dignity. Supporting workers at low-wage jobs is key to achieving that goal—especially at a time when many have unemployed family members, must care for ill loved ones or are themselves ill, or risk their lives daily at workplaces where they could be exposed to the coronavirus.

A strong minimum wage is an effective tool for building low-wage workers’ economic security:

- Research shows that raising the minimum wage can bring lasting boosts to families’ income,[i] reduce poverty,[ii] improve children’s health,[iii] and put the next generation on a path to success.[iv]

- These benefits are greatest for women and workers of color. About 30 percent of workers expected to benefit from Maryland’s $15 minimum wage are Black, while another 12 percent are Latinx.[v] Altogether, it is expected that half of all benefiting workers are people of color. Likewise, 55 percent of workers estimated to benefit from Maryland’s minimum wage increase are women.

On the other hand, freezing our minimum wage would have the opposite effect—lowering family incomes for years to come, increasing poverty, putting children at higher risk of illness, and blunting their long-term prospects. And the greatest harms would fall on women and workers of color.

The fact is, the minimum wage law now on the books is already weaker and slower to take effect than the original, economically sound proposal. Every delay means thousands in lost wages for every low-wage worker and greater economic hardship for years to come. The bill initially introduced in 2019 would have brought most workers’ hourly wages to $15 by July 2023. Under current law, a typical worker will not reach $15 until 2025, resulting in about $9,000 in lost wages through 2025 and more in later years due to the lack of inflation adjustment.[vi] Delaying one scheduled increase—a step allowed under current law—would cost a typical worker another $7,300. A proposal to freeze the minimum wage at $11 for two years—which rests on shaky legal ground, at best—would cost a typical worker $14,600 by 2026.

Already, there is nowhere in Maryland where even a single adult working full time and not caring for children can afford a basic living standard on less than $15 per hour—and low wages are even more inadequate for workers who must support a family.[vii]Delaying scheduled minimum wage increases would slow the improvements Maryland workers were promised, even as other essentials like housing and health care continue to become more unaffordable.

Delaying wage improvements for low-wage workers is particularly unconscionable in consideration of the jobs these workers do. Low wages are often associated with jobs in the retail, accommodations, and food services industries. Many businesses in these industries are shut down for public health reasons, but those that remain open perform essential roles such as ensuring families are able to eat.

At the same time, freezing the minimum wage would also harm workers in a range of other, equally essential industries. For example, 15 percent of workers expected to benefit from Maryland’s $15 minimum wage law are in the economically vital construction, manufacturing, transportation, and warehousing industries.[viii] Another 15 percent work in often highly dangerous health care settings.

Amid a historic public health crisis and a deep economic downturn, we will all have to make sacrifices. The question is how those sacrifices will be shared. It would be out of step with Marylanders’ values to walk back the promise we made to low-wage workers only a year ago to bring every job closer to a family-supporting wage. To break this promise to the essential workers who daily risk their lives to keep Marylanders fed, safe, and cared for would be a betrayal of these values.

Lower Wages Would Mean a Steeper Downturn and a Slower Recovery

In an economic crisis like the one we are experiencing now, maintaining consumer demand is key to easing the pain and bringing about a speedy recovery. Weakening the minimum wage is precisely the wrong response to this situation.

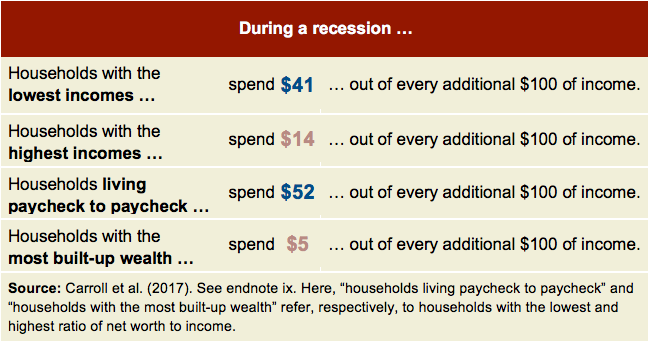

More than anyone else, families living paycheck to paycheck quickly cycle every dollar of income back into the local economy by buying essentials.[ix] A higher minimum wage means higher incomes for precisely the families who will spend that money fastest. This, in turn, means stronger sales at local businesses, which allows them to preserve more jobs. In contrast, freezing the minimum wage further squeezes families who already struggle to afford the basics. When families have no choice but to cut back, this means less demand for businesses’ wares and fewer jobs to go around.

The loss in consumer spending from freezing the minimum wage would also mean lower sales tax revenues. At a time when we all must rely on public investments in things like public health, infrastructure, and education in a challenging new context, lower revenues will mean more pain for Maryland communities—and for our economy. State analysts have estimated that every $1 million in state budget cuts corresponds to up to 16.7 lost jobs (including 6.7 jobs lost in the private sector) and up to $1.2 million in lost take-home income.[x]

Corporate Lobbyists’ Claims Don’t Hold Water

The harms of freezing Maryland’s minimum wage at its current, inadequate level of $11 per hour are clear—a less humane, less fair economy; a deeper downturn and a slower recovery; and a betrayal of the workers who risk their lives to sustain Maryland communities. Meanwhile, the purported case for freezing the minimum wage is without merit.

The most rigorous economic research undermines catastrophic predictions about the effect of a higher minimum wage on the economy:

- A study published in 2019 examined 138 state minimum wage changes between 1979 and 2016. The study found no evidence of any reduction in the total number of jobs for low-wage workers and no evidence of reductions affecting subsets of the workforce such as workers without a college degree, workers of color, and young workers.[xi]

- A 2016 meta-analysis of 37 studies on the minimum wage published since 2000 found minimal employment effects, particularly for the vast majority of workers affected by the minimum wage who are at least 20 years old.[xii]

- A study published in 2016 assessed a range of statistical methods used in the literature to estimate employment effects of the minimum wage.[xiii] Analyses using a diverse set of credible approaches find negligible effects on employment. The authors identified analytical problems with methods that found negative effects, calling into question the suitability of these methods for distinguishing the effect of the minimum wage from preexisting labor market trends.

Furthermore, a growing body of research calls into question economists’ predominant focus on the relationship between the minimum wage and the total number of jobs available. The researchers note that low-wage labor markets are characterized by a high level of “churn.”[xiv] Rather than remaining at a single employer for a long period of time, low-wage workers often work at multiple employers during a single year—for reasons such as hours availability—with intermittent periods of unemployment. This means that even the (generally lower-quality) research that finds a modestly negative relationship between the minimum wage and the number of jobs available is consistent with all or a vast majority of low-wage workers ultimately taking home higher incomes, even if they work fewer hours. Indeed, the growing body of research linking a higher minimum wage to a long-term boost to families’ incomes lends credence to this thesis.[xv]

The strong evidence that raising the minimum wage is effective in increasing low-wage workers’ household income is particularly relevant during a recession. Maintaining consumer demand is key to easing the pain and bringing about a speedy recovery. High-quality empirical research makes clear that by raising families’ incomes, raising the minimum wage can effectively boost demand during a downturn. Conversely, freezing the minimum wage at its current, inadequate level locks in low purchasing power for low-wage workers, making it harder for them to afford necessities and needlessly depressing sales at local businesses.

Finally, two common arguments against a higher minimum wage do not stand up to scrutiny:

- Business location: Industries with the highest concentrations of low-wage employers are often tied to a particular place. For example, businesses engaged in accommodation and food services, retail trade, or residential care by nature serve a specific geographic area.[xvi] This means that employers cannot simply relocate to avoid paying higher wages.

- Automation: Because research and development is generally the most significant cost of automation technology, companies decide whether to automate jobs based more to the nationwide (or worldwide) labor market rather than on wages in a specific place. Once a company has successfully developed an automation technology, it is likely to deploy that technology in high-wage and low-wage areas alike. This means that we can expect Maryland’s minimum wage policy to have minimal effects on the pace of automation.

Taken together, this evidence makes clear that freezing Maryland’s minimum wage would make it harder for families to afford necessities, depress consumer demand, and bring no compensating benefit. For a healthy Maryland economy—one with a speedy recovery, strong job growth, and decent wages for all workers, regardless of their race, class, gender, or disability—proceeding with scheduled minimum wage increases in 2021 and 2022 is the right choice.

[i] Arindrajin Dube, “Minimum Wages and the Distribution of Family Incomes,” American Economic Association 11(4), 2019, https://ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aejapp/v11y2019i4p268-304.html

Keniv Rinz and John Voorheis, “The Distributional Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” U.S. Census Bureau Working Paper No. CARRA-WP-2018-02, 2018, https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2018/adrm/carra-wp-2018-02.html

Evan Totty and Ben Zipperer, “Panel Paper: Minimum Wages and Earnings in the Long Run: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management conference paper, 2018, https://appam.confex.com/appam/2018/webprogram/Paper26315.html

[ii] Dube (2019).

[iii] Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart, “Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes? A Systematic Review,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, October 2013, https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/money-children-outcomes-full.pdf The systematic review methodology involves defining in advance how researchers will identify relevant studies, as well as quality control measures to ensure that only studies with credible methodologies are included. This methodology protects against researchers cherrypicking studies that support their viewpoint.

George Wehby, Dhaval Dave, and Robert Kaestner, “Effects of the Minimum Wage on Infant Health,” NBER Working Paper No. 22373, June 2016, http://www.nber.org/papers/w22373.pdf

Kelli Komro, Melvin Livingston, Sara Markowitz, and Alexander Wagenaar, “The Effect of an Increased Minimum Wage on Infant Mortality and Birth Weight,” American Journal of Public Health 106(8), August 2016, http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303268

“Improving Health by Increasing the Minimum Wage,” American Public Health Association, November 2016, https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2017/01/18/improving-health-byincreasing-minimum-wage

[iv] Cooper and Stewart (2013).

[v] Christopher Meyer, “What a $15 Minimum Wage Would Mean for Maryland: Good Jobs, Secure Families, and a Healthy Economy,” Maryland Center on Economic Policy, 2018, http://www.mdeconomy.org/minimumwage/

See Table A-2a. Note: This analysis is based on the 2018 $15 minimum wage bill, which is nearly identical to the bill as introduced in 2019. Because of amendments to the bill and the impact of the coronavirus-driven recession, the demographics of affected workers may differ somewhat. However, it is highly likely that women and workers of color will disproportionately benefit from a $15 minimum wage.

[vi] Based on 1,560 hours per year, equivalent to a 35-hour week. It is expected that 64 percent of workers affected by a $15 minimum wage work full time.

[vii] Economic Policy Institute Family Budget Calculator, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/

[viii] See Meyer (2018) Table A-3a.

[ix] Christopher Carroll, Jiri Slacalek, Kiichi Tokuoka, and Matthew White, “The Distribution of Wealth and the Marginal Propensity to Consume,” Quantitative Economics 8(3), 2017, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3982/QE694

[x] “Economic Impacts of Reducing the Corporate Income Tax Rate,” Maryland Department of Legislative Services, 2013, http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/Pubs/BudgetFiscal/2013-Corporate-Income-Tax-Analysis-Report.pdf

MDCEP calculations based on Exhibit 2 and Appendix 1.

[xi] Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer, “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3), 2019, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/134/3/1405/5484905

[xii] Paul Wolfson and Dale Belman, “15 Years of Research on US Employment and the Minimum Wage,” Labour 33(4), 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/labr.12162

“Meta-analysis” refers to a quantitative synthesis of results from multiple empirical studies. For demographics of workers affected by a $15 minimum wage, see Meyer (2018) Table A2-a.

[xiii] Sylvia Allegretto, Arindrajit Dube, Michael Reich, and Ben Zipperer, “Credible Research Designs for Minimum Wage Studies: A Response to Neumark, Salas, and Wascher,” ILR Review 70(3), 2017, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0019793917692788

[xiv] David Cooper, Lawrence Mishel, and Ben Zipperer, “Bold Increases in the Minimum Wage Should Be Evaluated for the Benefits of Raising Low-Wage Workers’ Total Earnings,” Economic Policy Institute, 2018, https://www.epi.org/publication/bold-increases-in-the-minimum-wage-should-be-evaluated-for-the-benefits-of-raising-low-wage-workers-total-earnings-critics-who-cite-claims-of-job-loss-are-using-a-distorted-frame/

[xv] See Dube (2019), Rinz and Voorheis (2018), and Totty and Zipperer (2018).

[xvi] These three industries include 41 percent of workers expected to take home higher wages once Maryland’s $15 minimum wage is phased in. See Meyer (2018) Table A-3a.